Summary

The aim of this article is to acquaint the professional public with the summary results of the assessment of chemical status and ecological status/potential of surface water bodies “river” and “lake” categories in the Czech Republic for 2016–2018. This assessment is one from the basis for preparation of the Third River Basin Management Plan (2021–2027) at all its levels: sub-basin plans, national plans, and international plans of the Elbe, Danube, and Oder river basin districts. The status assessment was carried out by T. G. Masaryk Water Research Institute p.r.i., and by Biology Centre CAS in cooperation with Hydrosoft Veleslavín and the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute. The results of the surface water monitoring programmes were used for status assessment.

Due to the “one out – all out” principle, 51.1% of surface water bodies in the “river” category (out of a total 1,045 river bodies) and 20.5% of surface water bodies in the “lake” category (out of 73 lakes) failed to achieve good chemical status. 94.6 % of surface water bodies in the “river” category and 86.3% of surface water bodies in the “lake” category failed to achieve good ecological status. 16.7% of surface water bodies in the “river” category and 43.8% in the “lake” category were not classified due to missing monitoring data.

The failure to achieve good chemical status was mainly influenced by the occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, namely fluoranthene and benzo(a)pyrene. Some new priority substances, such as cypermethrin, dichlorvos, and PFOS did not achieve good chemical status in all of the monitored profiles; nevertheless, the scope of their monitoring is still very low (4% of profiles). A similar situation was found in the case of mercury and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in biota monitoring. The limiting parameter for achieving good ecological status/potential is still the total phosphorus and dissolved oxygen for the “river” category and the total phosphorus and transparency for the “lake” category. From the evaluated biological quality elements, phytobenthos and benthic macroinvertebrates for the category “river” and phytoplankton for the category “lake” most often contributed to failure in good ecological status/potential.

It is difficult to compare the results of the assessment of chemical status and ecological status/potential between the Second and Third River Basin Management Plans due to adjustments and changes in the methodological procedures.

Introduction

As part of the preparation of the Third River Basin Management Plan for the period 2021–2027, it was necessary to carry out an assessment of the status of surface water bodies from water monitoring data carried out by individual river basin managers and the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute (CHMI). This assessment is an important basis for the elaboration of all levels of river basin plans and serves individual river basin managers both to formulate measures to achieve good water status, as well as a basis in other areas of water management activities. The assessment is performed for each water body of the “river” and “lake” categories. The decisive period for the preparation of the assessment of the situation was 2016–2018; in some cases it was the previous evaluated period, 2013–2015 [1]. The evaluation was carried out in accordance with the requirements of European [2] and national legislation [3–4] according to the updated methodological procedures of evaluation, which are summarized in the following section.

Methodological procedures used

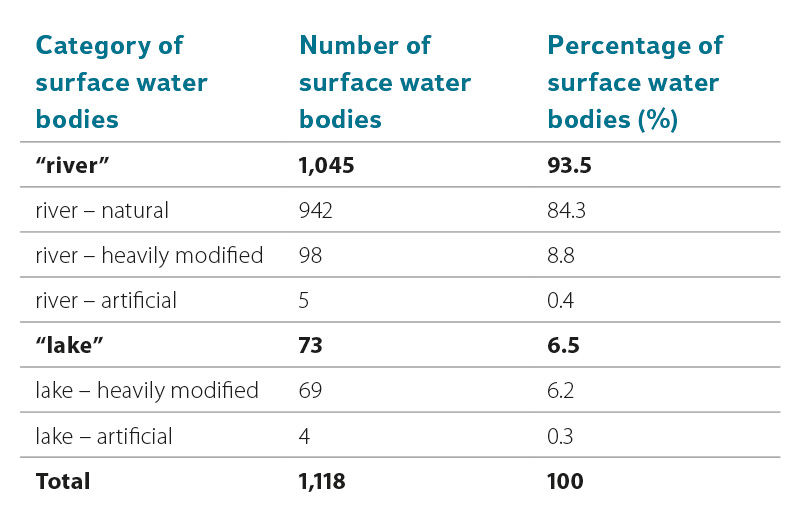

The assessment of surface water body status is divided into the assessment of chemical status and the assessment of ecological status in natural surface water bodies, and the ecological potential in heavily modified and artificial surface water bodies. The number of these bodies for the whole of the Czech Republic is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Surface water bodies – categories valid for the third planning cycle

Compared to the second planning cycle (from the evaluation in 2010–2012), the number of surface water bodies changed only slightly; however, a significant change occurred in the re-definition of heavily modified bodies of the “river” category in 2019. The reason was adjustment of the methodology for identifying heavily modified water bodies so that it follows up on the evaluation of the significance of hydromorphological effects. A total of 49 water bodies previously designated as “natural” have now been defined as “heavily modified”; in contrast, 40 previously “heavily modified” water bodies have now been defined as “natural”.

The evaluation was carried out on the basis of the actual measured data of surveillance and operational surface water monitoring in the representative profiles of surface water bodies (in several cases, one representative profile was used to evaluate two or more bodies in the “river” category). The assessment is then applied to the whole water body. If no data were available in the period 2016–2018, the period 2013–2015 is assessed for Biological quality elements or chemical status parameters. Due to the rotation of the profiles after three years, data from both periods were used in full when evaluating biota.

An overview of the methodologies used to assess the status is given in the literature for this article [5–18]. The following text mentions significant differences from the previous evaluation.

Chemical status

For the first time, in compliance with Directive 2013/39/EU and Government Regulation No. 401/2015 Coll., the bioavailable form of dissolved metals of nickel and lead was evaluated according to the methodology [17]. It depends on the concentration of the respective dissolved metal, the concentration of dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and the reaction of water (pH) and calcium (Ca). The bioavailable concentration of metals calculated using appropriate software tools [19–20] is always lower than the concentration of the dissolved form of the metal. This resulted in a more favourable evaluation of nickel and lead than in the evaluation for the second planning cycle.

A fundamental change compared to the previous method of evaluation was the approach to situations where none of the chemical status indicators was monitored in the given representative profile. Due to precaution, the condition of such a body was designated as “unknown” (formerly “good”). Based on the expert assessment, the relevant river basin manager could designate its status as “good” if there was no significant anthropogenic pressure (point, diffusion, or surface nature of pollution) in the assessed surface water body.

Ecological status/potential

Bodies in the “river” category

General physico-chemical quality elements

The Methodology for the assessment of General physico-chemical quality elements of the ecological status of flowing surface water bodies [11] and the Methodology for the assessment of General physico-chemical quality elements of the ecological potential of surface water bodies [15] were used to evaluate general physico-chemical parameters of surface water bodies of the “river” category for 2016–2018. In contrast, for the second planning cycle, different limits were used for the evaluation of the “river” category bodies, both the same for ecological status and potential (limit values between good and moderate status/potential in the methodology [11] are now stricter than limits used in the evaluation of previous periods). In addition to the change in characteristic values, there is also a change in some parameters. Thus, the original methodology could be used to assess the ecological potential of heavily modified and artificial water bodies for the “river” category [13] (in the previous planning cycle it could not be used as ecological potential limits were in some cases stricter than status limits). Therefore, it is not possible to compare the evaluation results between the second and third cycle.

Biological quality elements

Evaluation of Biological quality elements (with the exception of fish) was carried out in the third planning cycle according to the previous methodological procedures for the second planning cycle, in which the results of the

intercalibration comparison were incorporated [21]. The tightening of the originally set class boundaries (used for the second planning cycle) affected the phytobenthos and macrophytes Biological quality elements. Changes in the classification of the resulting values of Environmental Quality Ratio (EQR) indexes are shown in the updated methodologies [6–7]. The methodology for the assessment of the biological quality element of fish has been revised [5]. Although it is based on computational procedures of the original methodology [22], the list of taxa (including traits) was revised, new traits were added (non-origin of the taxon), and assessment reliability parameters were modified; this also affected which water body categories can be assessed (i.e., it evaluates the condition of water bodies for categories of the 4th–9th Strahler stream order. Unlike the previous methodology, it does not evaluate lower stream orders: the evaluation would be unreliable. So, while the procedures and results of the evaluation of other Biological quality elements are for the most part comparable to the previous period, the procedures for the evaluation of fish cannot be compared: the evaluation results are difficult to compare.

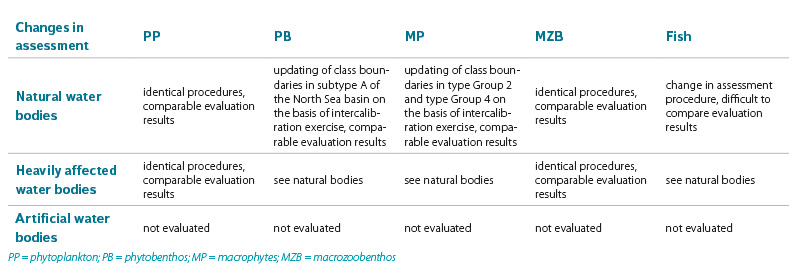

Table 2. Changes in biological element assessment and results of category “river” between second and third planning cycle

As in the second planning cycle, the assessment of the phytobenthos and macrophyte Biological quality elements in heavily modified water bodies is identical to the assessment procedure for natural water bodies [6–7]. The assessment of the ecological potential of macrozoobenthos and phytoplankton in heavily modified water bodies was performed according to the original methodologies [9–10] and the procedure used is identical for the second and third planning cycles. Changes in the assessment of Biological quality elements for water bodies of the “river” category are summarized in Table 2.

Specific pollutants

The assessment of River Basin-Specific Pollutants (RBSP) is identical for ecological status and potential. The methodology from the second planning cycle was used for the evaluation. The only difference is that if no parameter was monitored and/or classified in the body during the evaluated period; the ecological status/potential of the water body was marked as “unknown”.

Hydromorphology

In the second planning cycle, hydromorphological quality elements were not evaluated, nor was the evaluation of the significance of hydromorphological effects at the level of the entire Czech Republic. Thus, a methodology for assessing the significance of hydrological and morphological impacts [23] was created for the third cycle and, based on it, significant impacts were identified in the plans in terms of hydrological regime, continuity, and morphological conditions. Significant morphological impacts were then included in the results of ecological status and potential, but as a supporting quality element of the evaluation of Biological quality elements, so they did not enter the principle of “one-out – all-out”.

Bodies in the “lake” category

The evaluation of the ecological potential of lakes was carried out using the same methodological procedures as for the second planning cycle [12, 14]; however, due to the lack of data, only phytoplankton was evaluated from the Biological quality elements.

It is still generally true that the final status is given by the worst result of the evaluation of individual parameters of all quality elements of the chemical status and ecological status/potential (with the exception of hydromorphology).

The reliability procedure for the assessment of ecological status/potential and chemical status has been adjusted according to the reporting requirements [24] and is defined in the methodology [23]. Reliability is now determined in three categories (high, moderate, and low).

Results

The status of surface water bodies is determined by the chemical status and ecological status, or ecological potential in the case of heavily modified and artificial water bodies. The results of the status assessment aggregated for the whole of the Czech Republic (in selected cases also by individual indicators) are briefly processed in the form of tables, maps, and graphs in the following text.

Chemical status

The chemical status is classified as “good” or “failing to achieve good status” according to the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC [2]. If any Environmental Quality Standard (EQS) of the evaluated priority substances is exceeded then good status is failing to achieve good status.

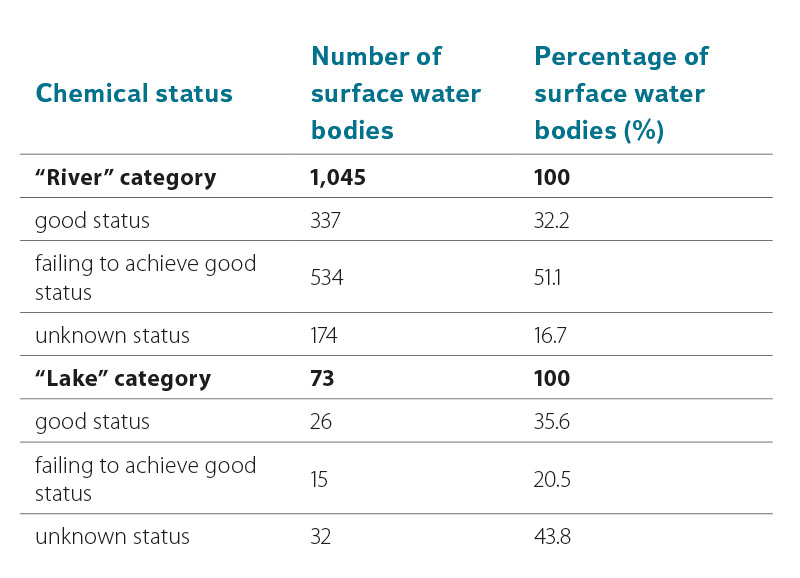

Table 3. Chemical status of surface water bodies in categories “river” and “lake”

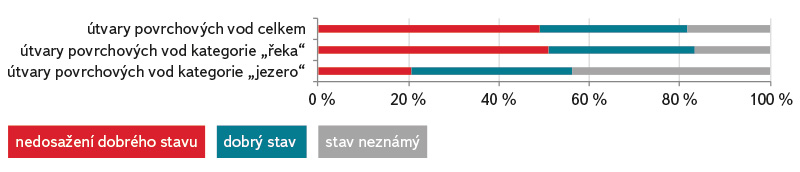

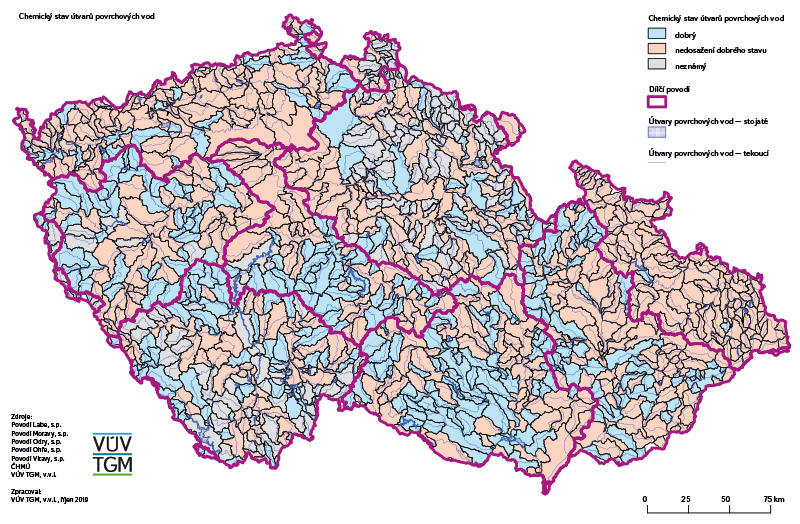

Fig. 1. Chemical status of surface water bodies in categories “river” and “lake”

Good chemical status was achieved in 32.2% of surface water bodies in the “river” category and 36% of bodies in the “lake” category (Figures 1 and 2, Table 3). Out of the entire 1,118 surface water bodies, 32.5% of them were classified as having good chemical status; 18.4% were not classified, mostly due to missing monitoring data and, in some cases, due to insufficient number of measurements per year, and their chemical status was marked as “unknown”. Compared to the results of the surface water chemical status assessment for the second planning cycle (2010–2012), a smaller number of water bodies (previously 60.9%) is now assessed as having good status. This is due to several factors:

- If none of the chemical status parameter was monitored in the given representative profile, its status was not marked as “good” in the current evaluation for the third planning cycle, but as “unknown” due to precaution. Only a small number of water bodies were subsequently marked as “good” by the river basin managers on the basis of an expert assessment (in the event that there is no significant anthropogenic pressure in the assessed surface water body). In the evaluation for the second planning cycle, the chemical status was not classified in only four water bodies (out of 1,121).

- In the third planning cycle, the monitoring of priority substances increased significantly, which led to an increased number of non-compliant bodies that were previously identified as being in good status.

- For the second planning cycle, the so-called new priority substances have not yet been evaluated, the EQS of which entered into force on 22nd December 2018. Some of these substances have caused the failure to achieve good chemical status (cybutryn, cypermethrin, dichlorvos, heptachlor + heptachlorepoxide, PFOS, and terbutryn) (Table 4).

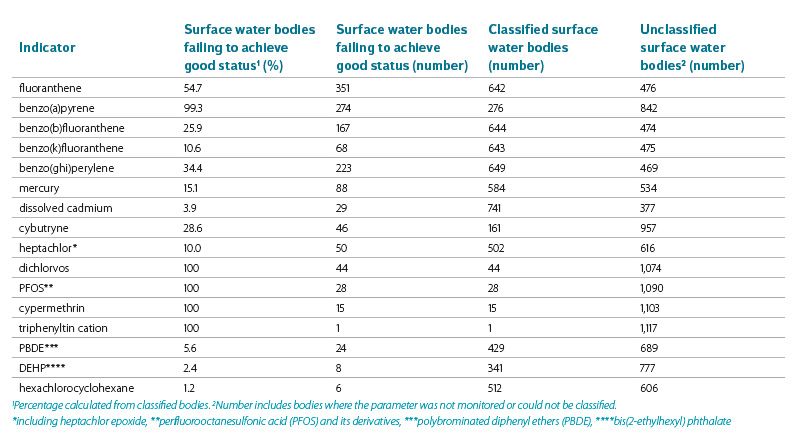

Table 4. Selected pollutants causing failure to achieve good chemical status in 2016–2018

There was a significant improvement in the case of the evaluation of dissolved nickel and dissolved lead, when the bioavailable concentration of these metals (which is always lower than the concentration of the dissolved form) was evaluated for the first time. In the long term, the most problematic parameters in terms of exceeding the EQS are mercury and PBDE (in the biota matrix) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the water matrix (fluoranthene, benzo(a)pyrene). The latter pollutant is also problematic in terms of the difficulty of achieving a sufficiently low limit of quantification by laboratory techniques in relation to the EQS value expressed as an annual average. Among the new priority substances, the limits for the average annual concentration in any of the classified surface water bodies for cypermethrin, PFOS, and dichlorvos are not reached; even here, the limit values (EQS) are very low. However, new priority substances are currently monitored and classified in a small number of bodies.

Fig. 2. Chemical status of surface water bodies for the period 2016–2018 in the Czech Republic

Ecological status/potential

The ecological status/potential assessment is given by the aggregation of sub-assessments of the Biological quality elements phytoplankton, phytobenthos, macrophytes, macrozoobenthos, and fish in the “river” category; in the case of the “lake” category only phytoplankton, macrophytes, and fish, and other quality elements including general physico-chemical parameters, specific pollutants, and hydromorphology. The final assessment of the ecological status/potential is given by the least favourable assessment of the given quality element, with the exception of hydromorphology.

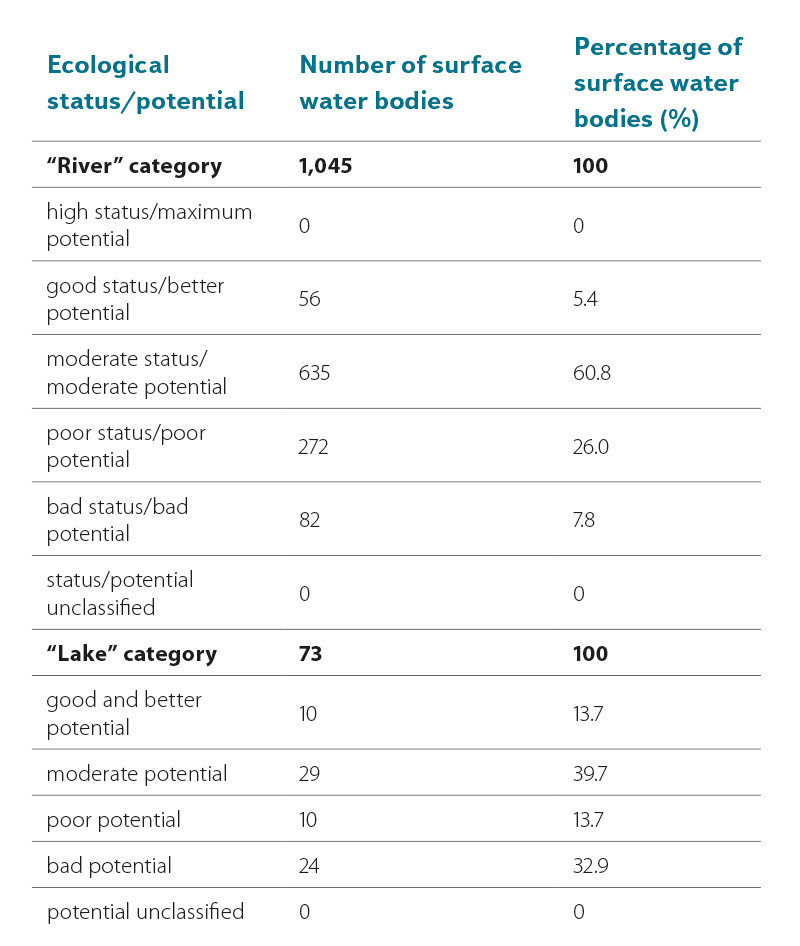

Only 5.4% of surface water bodies in the “river” category and 13.7% of bodies in the “lake” category were assessed in good status or in good and better potential during the 2016–2018 evaluation period (Table 5).

Table 5. Ecological status/potential of surface water bodies in categories “river” and “lake”

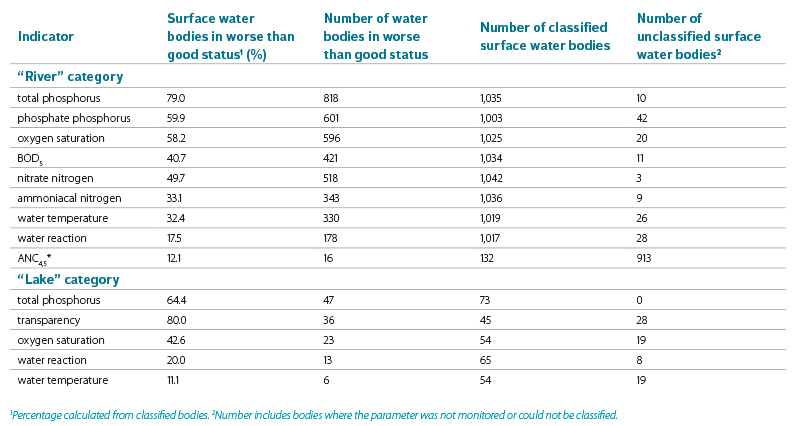

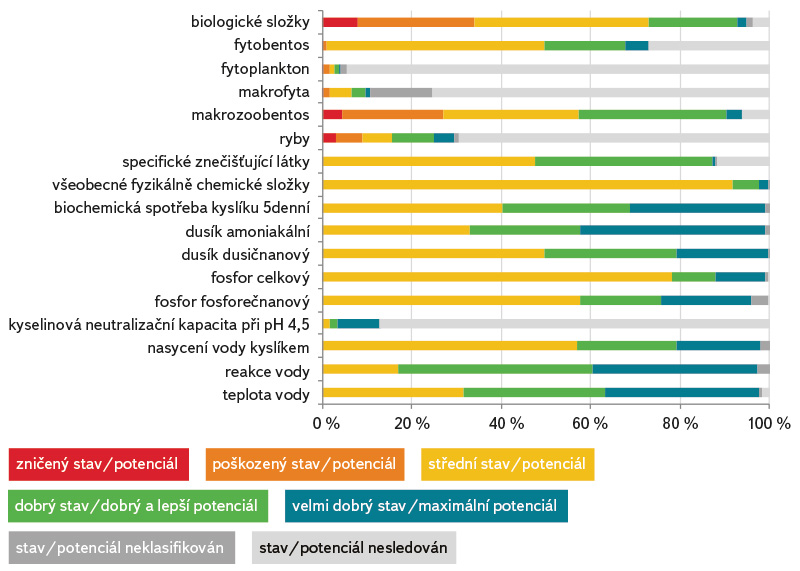

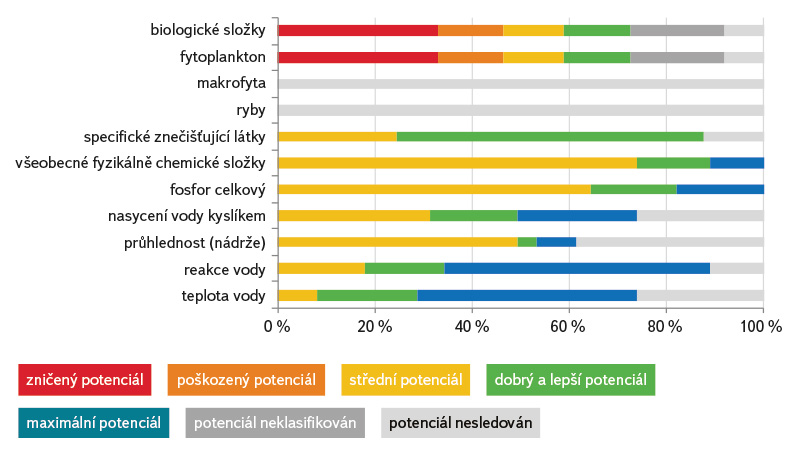

The assessment of individual quality elements of ecological status/potential and individual general physico-chemical parameters for the “river” category can be seen in Fig. 3, and for the “lake” category in Fig. 4. In the case of bodies in the “river” category, the General physico-chemical quality elements (91.9%) and only subsequently the Biological quality elements as a whole (73.4%) contribute the most to the unsatisfactory condition. The “lake” category is similar. This high rate of non-compliance with good ecological status/potential in the case of rivers is due to the use of stricker type-specific values of physico-chemical quality elements of ecological status [11]. The limiting parameter of the general physico-chemical quality element to achieve status improvement is total phosphorus, followed by oxygen conditions (rivers) and transparency (lakes) (Table 6).

Table 6. Surface water bodies in moderate status/potential – physico-chemical parameters

In the case of total phosphorus, the rate of exceedance of type-specific values (non-compliance index) for good status/potential in rivers averaged 3.4 (median 2.6). The highest rate of exceedance is typical for small streams flowing through human settlements; the highest non-compliance indices (above 10) were found mainly in the sub-basin of the rivers Thaya and the Upper and Middle Elbe. Only in 15% of unsatisfactory water bodies in the “river” category was the rate of exceedance of type-specific values low, in the range of 1.01 to 1.5. Similarly, the oxygen saturation non-compliance index (minimum) averaged 2.7 (median 1.25). In less than 70% of non-compliant water bodies, the limit value between good and moderate status was only slightly exceeded in this parameter (non-compliance index up to 1.5).

Fig. 3. Ecological status/potential of surface water bodies in the category “river” evaluated by physico-chemical parameters in 2016–2018 period

The results of the assessment of surface water bodies category river according to the biological quality element of macrozoobenthos (which is the most used biological quality element) are as follows: 32.4% in the middle status, 23.6% in the poor status, and 4.8% in the bad status. A total of 599 water bodies (out of 982 classified bodies) in the “river” category are in less than good status. The number of monitored surface water bodies by the macrozoobenthos quality element was significantly increased compared to the second planning cycle. The least favourable status in this quality element is evident in the surface water bodies of the Upper and Middle Elbe river basins, while the best in the Lower Moldau river basins and tributaries of the Danube.

In total 519 water bodies in the “river” category, which represent 67.9% of 764 classified bodies, are assessed unfavourably by the biological quality element of phytobenthos (less than good status); of them, only 1% of the bodies are in a poor status and not a single water body is in the bad status. There was also a significant increase in the number of monitored water bodies in this quality element.

Fish were evaluated in a total of 309 water bodies in the “river” category. The fish assessment methodology was revised in 2019 [5]. Half of the classified water bodies did not meet good status (52.4%). The moderate status/potential contributes 22.3% to the unfavourable status, the poor status/potential 19.7% and the bad status/potential 10.4%. The least favourable status in this quality element is evident in the surface water bodies of the Thaya river basin, while the best is in the Upper Oder river basin.

Fig. 4. Ecological status/potential of the surface water bodies category “lake” evaluated by physico-chemical parameters in 2016–2018 period

In surface water bodies in the “lake” category, the only biological quality element assessed was phytoplankton. Of the 73 water bodies in this category, the ecological potential in 53 reservoirs was assessed. Only 10 of them showed good and better potential. The bad potential prevails in 24 reservoirs (Fig. 4). As stated above, total phosphorus and transparency are the most important factors in not meeting the requirements for good potential. In the case of total phosphorus, 47 lakes failed; the rate of exceedance of type-specific values (non-compliance index) for good potential averaged 3.8 (median 2.3). The highest rate of exceedance is typical for ponds. In one third of the water bodies in the “lake” category, the exceedance rate was as low as 1.5. Similarly, the rate of exceedance of type-specific values in reservoir transparency for good potential averaged 3.6 (median 3.1). For 31% of non-compliant reservoirs, transparency was exceeded only slightly (non-compliance index up to 1.5).

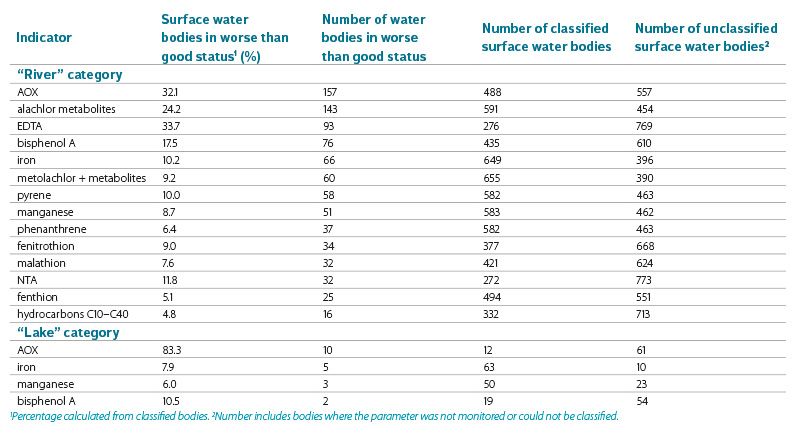

Table 7. River basin specific pollutants with high frequency of exceedance of environmental quality standards (EQSs)

Of the specific pollutants, the most problematic parameters are Adsorbable Organic Halides (AOX), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), alachlor metabolites, and bisphenol A (Table 7). The average rate of exceeding EQSs (average) of Government Regulation No. 401/2015 Coll. [25] with these parameters range from 1.5 to 3.7 (1.5 for AOX, 1.65 for bisphenol A, 2.8 for alachlor metabolites, and 3.7 for EDTA). The streams most burdened by AOX are located in the Eger, Lower Elbe, and other tributaries of the Elbe river district; however, it is also the only catchment where AOX are monitored in practically all water bodies in the “river” category.

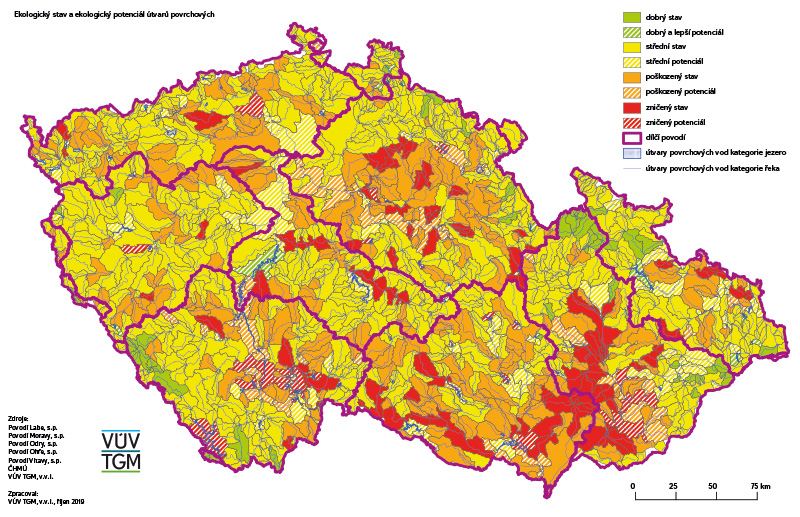

The overall ecological status/potential in the Czech Republic is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Ecological status/potential of surface water bodies for the period 2016–2018 in the Czech Republic

Conclusion

The implemented assessment of the surface water status prepared for the third planning cycle using the principle of “one out – all out” shows that 51.1% of surface water bodies in the “river” category (out of 1,045 bodies) and 20.5% of bodies in the “lake” category (out of 73 bodies) are failing to achieve good chemical status; in 16.7% of the surface water bodies in the “river” category and in 43.8% in the “lake” category bodies, their chemical status was assessed as “unknown”. 94.6% of surface water bodies in the “river” category (out of 1,045 bodies) and 86.3% of bodies in the “lake” category (out of 73 bodies) are in less than good ecological status/potential. The assessment was carried out as a direct assessment of the results of monitoring programmes of the Water Basin state-owned enterprises (Povodí) for the period 2016–2018, with monitoring results for the period 2013–2015 also being used in some justified cases (e.g. due to “rotation” of biota monitoring profiles).

The failure to achieve good chemical status was mainly influenced by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, specifically fluoranthene and benzo(a)pyrene; however, differences between individual sub-basins can be noted. Although some new priority substances (cypermethrin, dichlorvos, and PFOS) failured to achieve good chemical status in each monitored profile, the scope of their monitoring and classification are still very low (maximum 4% of profiles). The situation is similar for the results of priority substances in biota for mercury and brominated diphenyl ethers (monitored in a maximum of 3% of profiles). The limiting parameter for achieving the improvement of the ecological status/potential is still the total phosphorus and oxygen conditions for the “river” category and total phosphorus and transparency for the “lake” category. In the Biological quality elements, phytobenthos and macrozoobenthos most often contributed to the unfavourable assessment of surface water bodies in the “river” category, and phytoplankton in the “lake” category.

Comparison of evaluation results for the second and third planning cycles is problematic and incomparable for a large part of the evaluated quality elements due to the update of status assessment procedures, change of identification of heavily modified bodies for water bodies of the “river” category, and significant expansion of monitored parameters. A possible comparison of evaluations to determine possible improvement or deterioration can thus be realized only for individual parameters and quality elements for which there was no change in the limits or the evaluation procedure, and only for river profiles that were classified for the given parameter in both planning cycles. Hydromorphology as a supporting quality element of ecological status assessment did not enter the principle of “one-out – all-out” assessment. The original derived limits between good and moderate status were used for the first time for general physico-chemical parameters in the assessment of ecological status and the bioavailable form of nickel and lead in the assessment of chemical status. The methodology for assessing the ecological status of fish has been completely redesigned in order to better characterize the status of the stream and to allow the design of appropriate improvement measures. A significant change was also the classification of the chemical status as unknown in some cases where no priority substance was evaluated in the body.

More detailed results in the form of maps, graphs, and tables are on the HEIS TGM WRI, p.r.i., site: heis.vuv.cz/projekty/rsv.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the Water Basin state-owned enterprises (Povodí) for the data provided and consent to publish the summary results of the surface water status assessment. We also give thanks for the provided data and results to other cooperating employees of professional entities: CHMI, Hydrosoft Veleslavín, s.r.o., Biological Centre of the ASCR, p.r.i.