ABSTRACT

Per- and polyfluorinated compounds (PFAS), a group of fluorinated compounds of anthropogenic origin, have been classified as a persistent organic substances of significant concern due to their chemical properties, widespread use in a number of industrial sectors, environmental spread, long term bioaccumulation potential, and resulting risk to human health. This article brings an overview of current knowledge about the occurrence of PFAS in the environment, mainly in surface, ground, and drinking water and about the methods of their removal from contaminated water. Furthermore, the legislative requirements regarding PFAS at the level of the EU and Czech Republic are summarised here, including the list of compounds according to the Directive of the European Parliament and the Council 2020/2184 and the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and the Council 2008/105/EC.

The article also includes an overview of analytical methods for determination of PFAS, including trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and the determination of total organic fluorine. The methods are generally based on liquid chromatography coupled with mass detection. Differences are primarily in sample pre-treatment. The main attention is focused on a summary of relevant data PFAS monitoring in surface water from all Czech Republic territory. Until 2022, only perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and (except for the Odra and Ohře basins) perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) were consistently monitored in surface waters in the Czech Republic. Detection limits of methods used in individual basins were different; therefore, an objective summary of relevant data about PFAS monitoring in the Czech Republic is impossible. Methodologies enabling determination with higher sensitivity and, in particular, a wider range of monitored substances are gradually being introduced with the expansion of analytical possibilities. From 2023, monitoring of substances from PFAS group compounds was introduced in individual basins on a wider scale, including pilot monitoring, which is presented in this article.

INTRODUCTION

The history of per- and polyfluorinated substances (PFAS), the so-called “forever” chemicals, began in 1938, when the chemist Roy J. Plunkett, an employee of DuPont, accidentally discovered polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) during the manufacture of Freon. This new fluorinated plastic was patented by Kinetic Chemicals in 1941 (U.S. Patent 2,230,654) [1], and in 1945 the trademark Teflon was registered [2]. More than 7,000,000 compounds fall within the PFAS group. In order to unify and harmonise communication on PFAS among scientific, regulatory and industrial communities, recommended names, acronyms, structural formulae and CAS Registry Numbers have been proposed [3]. The OECD has identified more than 4,700 compounds on the basis of their CAS numbers [4]. PTFE, however, is not a fully typical compound. PFAS include PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid) and PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), which were first detected in the 1950s during the production of Teflon.

Current state of knowledge

PFAS have attracted considerable attention over the past 10 to 15 years. Thanks to their lyophobic and hydrophobic nature, they have found wide use in a range of sectors, for example in the textile and leather industries, in fire-fighting foams, surface protection agents, household products, food-contact packaging, the photographic industry, aviation hydraulic fluids, electroplating, and as surfactants in pesticides and other agricultural chemicals [5]. In the 1990s, these substances were identified at low concentrations in all parts of the environmental (water, soil, air, plants, living organisms) thanks to the development of analytical methods for their determination and advances in instrumentation, particularly the emergence of liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry [3, 6].

Due to the significant expansion of PFAS production, there has also been an increase since 2000 in publications addressing this group of substances, their sources and fate in the environment, and their harmful effects. In 2020, nearly 1,000 publications dealing with this issue were published [6].

The toxicity of PFAS to humans and their impact on ecosystems currently receive extraordinary attention. An increasing number of substances from this group are being monitored regularly, and concentrations considered safe are decreasing. There is a need to gain a better understanding of the fate and impacts of these persistent chemicals on the environment, as it can be assumed that the burden on surface and groundwater by these substances is underestimated [7]. A publication by the authors of the current article [8] addresses a range of existing information on the applications, environmental release, and remediation technologies of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

In connection with the regulation and restriction of PFAS use, attention should also be paid to alternative substances, the monohydrogen-substituted perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (H-PFAS), which are also found in surface waters. In the Netherlands, a UHPLC-MS/MS method was developed, validated, and applied for the determination of these contaminants in surface water samples [9].

Very little information is currently available on the PFOA substitute known as GenX. Despite its lower bioaccumulative potential, this alternative substance may still pose a risk to both the environment and human health [10].

Given the global distribution of these chemicals, studies have been conducted to monitor their presence in developing countries in water samples and other samples from the abiotic environment and biota. PFAS were identified in 72 % of the samples [11, 12].

PFAS clearly represent a global problem. Levels of four selected perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAA) – perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) – have been tested in various global environmental media, namely rainwater, soils, and surface waters. Among other findings, it has been shown that PFOS levels in rainwater in some inland areas of the European Union often exceed the environmental quality standard for surface waters. It is therefore crucial that the use of these substances is restricted as rapidly as possible [13, 14].

Current efforts by the European Commission to initiate discussions on the largest proposal to restrict PFAS in history reflect the poor global situation regarding PFAS accumulation in the environment and their health impacts. However, a comprehensive analysis is still lacking. Interest in the issue has been successfully raised, with the focus of research gradually shifting towards ecological questions. The involvement of developing countries, however, is limited, despite the fact that PFAS exposure in these regions is extremely high. It is therefore necessary to pursue globally interconnected and multidisciplinary approaches to address issues related to PFAS [15]. Other studies also provide a critical review of the global occurrence and distribution of these persistent chemicals in waters, including wastewater [16, 17].

In Sweden, PFAS have been detected in both raw and drinking water, as well as in groundwater [18, 19].

In the Czech Republic, PFAS were tested in tap water. In 192 drinking water samples from across the country, 28 PFAS were analysed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry following solid-phase extraction. It was found that the occurrence of PFAS in drinking water in the Czech Republic is very low compared with other European studies. Approximately 1 % of the analysed samples could present a potential health risk [20, 21]. In seven locations on the Svitava and Svratka rivers in the Brno urban development, the occurrence of perfluorinated substances in water and fish blood plasma was monitored. Concentrations of PFHxS, FHUEA, FOSA, and N-methyl FOSA were below the detection limits. The main component in fish blood was PFOS, followed by PFNA and PFOA. In water, the primary detected compound was PFOA, followed by PFOS and PFNA. A significant correlation was observed between PFOA concentrations in blood plasma and in water (r = 0.74) [22]. Arnika has also monitored the occurrence of PFAS together with brominated flame retardants in Prague and its surroundings. High concentrations were measured in the Kopaninský stream. The values were significantly higher than those commonly found in surface waters in Europe. In this case, the source of pollution may be Václav Havel Airport [23].

As early as 2010, contamination of the Rhine river was monitored. Seventy-five water samples were collected along the entire course of the Rhine river, from Lake Constance to the North Sea, including several major tributaries such as the Neckar, Main, and Ruhr rivers, and waters from the Rhine–Meuse delta, specifically the Meuse and Scheldt rivers. The aim was to identify possible sources of contamination [24].

PFAS were also monitored in the Danube river basin. A total of 82 PFAS and 72 other suspected compounds were identified in 95 samples. Many of the substances detected are not currently regulated [25].

With the increasing information on toxicity and population exposure, concerns arose regarding the impact on human health. Several studies have been conducted examining the relationship between PFAS concentrations in blood serum and in drinking water [26, 27]. PFAS have also been detected in breast milk and infant formula [28].

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), which belongs to the ultrashort-chain subgroup of PFAAs, is included in the revised European Commission directives. It is a highly persistent compound, with concentrations in parts of the environment (soil, water, air, plants, plant-based foods, and human serum) increasing significantly. TFA is a transformation product of many PFAS and is also released into the environment from industrial TFA production. Studies on the occurrence of TFA in the environment, including surface waters, show that over the past 20 years its concentrations in all parts of the environment have increased severalfold and are currently many times higher than those of other per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Data on the toxicity and ecotoxicity of TFA are limited, but it is nevertheless clear that there is a potential global risk of its irreversible accumulation [29, 30].

Removal of PFAS from wastewater

One of the key tasks is to identify a suitable sorbent for removing PFAS from contaminated water. Biochar appears to be a cost-effective and environmentally friendly adsorbent for the elimination of PFAS [31]. Other potential methods for removing not only perfluorinated substances include ozonation, granular activated carbon, and membrane processes using reverse osmosis. However, PFAS were not removed by ozonization; these chemicals were effectively eliminated using physical methods, such as adsorption on activated carbon and processes based on reverse osmosis membranes [32]. Several magnetic materials, including iron oxides, ferrites, and magnetic carbon composites, also appear to be effective adsorbents for the removal of PFAS from water. These substances have demonstrated considerable potential for use in various environmental remediation applications, as well as in the treatment of PFAS-contaminated water [33]. Mixed-matrix membrane technology removes more than 99 % of PFAS from wastewater [34]. A concise summary of the occurrence, transformation, and removal of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) was prepared by Lenka et al. [35]. They also highlight that information on PFAS is particularly scarce for developing countries. Another study provides a comprehensive review of PFAS sources and their remediation [36].

Another study focused on the fate and transport of PFAS and inorganic fluoride in a municipal WWTP operating a sewage sludge incinerator (SSI). A robust statistical analysis characterised concentrations and mass flows across all primary influents and effluents of the WWTP and SSI, including emissions from thermal treatment into the air. A PFAS removal efficiency of 51 % indicates that the SSI can only partially eliminate PFAS [37]. An overview of the current state of research on treatment technologies suitable for the removal of PFAS from the environment, particularly from water, is provided in the publication Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Treatment Technologies [38].

PFAS Legislation at the EU and Czech Republic levels

Legislative instruments are the primary means of limiting perfluorinated organic compounds in the environment. One of the first measures was the inclusion of selected perfluorinated organic compounds on the list of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) under the Stockholm Convention [39]. Under Article 3 of the Convention, parties and organisations (signatories) are required to prohibit and/or adopt the legal and administrative measures necessary to eliminate: the production and use of the chemicals listed in Annex A; the import and export of the chemicals listed in Annex A; and to restrict the production and use of the chemicals listed in Annex B of the Convention. The Annex A list (Elimination) of the Stockholm Convention includes perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), its salts, and related compounds that may potentially degrade to PFHxS, as well as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), its salts, and related compounds that may potentially degrade to PFOA. In the case of PFOA, certain uses or products are subject to specific exemptions, including applications in the photographic industry, some medical uses, the textile industry (production of protective clothing for environments where there is a risk of adverse effects on human health), and in fire-fighting foams for the suppression of flammable liquid vapours and the extinguishing of flammable liquid fires (Class B fires). However, by 2025 at the latest, the use of fire-fighting foams containing or potentially containing PFOA, its salts, and PFOA-related compounds must be restricted to locations where all releases can be fully captured. The Annex B list (Restriction) of the Stockholm Convention includes perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), its salts, and perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride. Use is permitted in electroplating processes within closed systems, in fire-fighting foams for the suppression of flammable liquid vapours and the extinguishing of flammable liquid fires (Class B fires), and in insect baits containing the active substance sulfluramid (CAS no. 4151‑50‑2) for the control of ants of the genera Atta spp. and Acromyrmex spp., strictly for agricultural purposes.

Another measure is Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 of the European Parliament and of the Council [40], which sets restrictive conditions for the use or placing on the market of products containing perfluorinated substances within the European Union. According to Article 3 of this Regulation, the manufacture, placing on the market, and use of the substances listed in Annex I – whether as such, in mixtures, or in articles – are prohibited. In the case of PFOS, its salts, and related substances that degrade to PFAS, these substances may be present in mixtures or articles only as unintentional trace contaminants (Article 4, paragraph 1(b)), in quantities specified in Annex I to the Regulation. This annex has been amended several times for PFOS to tighten the limits on unintentional contamination. The use of PFOS in hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) electroplating processes in closed systems was permitted until 7 September 2025. A Member State could apply for an exemption for the above purpose by 7 September 2024, which could be granted for a maximum period of five years. Under an exemption pursuant to Regulation 2019/1021, the manufacture, placing on the market, and use of PFOA, its salts, and PFOA-related compounds could be authorised for the following purposes:

- photolithographic production and etching processes in semiconductor manufacturing, until 4 July 2025;

- photographic coatings applied to films, until 4 July 2025;

- oil- and water-resistant textiles for the protection of workers against hazardous liquids posing a risk to their health and safety, until 4 July 2023;

- invasive and implantable medical devices, until 4 July 2025

- the manufacture of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) for the production of:

- high-performance, corrosion-resistant membranes for gas filtration, water filtration, and medical textile applications,

- equipment for heat exchangers to recover heat from industrial waste,

- industrial sealing materials capable of preventing the release of volatile organic compounds and PM2.5 (particulate matter 2.5) into the environment, until 4 July 2023;

- In fire-fighting foam for the suppression of vapours released from flammable liquids and for extinguishing flammable liquid fires (Class B fires), until 3 December 2025.

However, a number of products containing PFAS that were placed on the market prior to the entry into force of the above Regulation are still in circulation (in use).

Derivatives of the above-mentioned substances are also subject to restrictions under REACH [41]. These include, for example, ammonium perfluorohexane sulfonate or tridecafluorohexane sulfonic acid in a 1:1 mixture with 2,2’-iminodiethanol. Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) is classified as a substance of very high concern [42]. In 2024, Commission Regulation (EU) 2024/2462 [43] established new restrictive conditions concerning perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), its salts, and related substances that may degrade to PFHxA. From 10 April 2026, the placing on the market or use of fire-fighting foams and foam concentrates for public fire brigades containing PFHxA and its salts at concentrations equal to or greater than 25 ppb, or PFHxA-related substances at concentrations equal to or greater than 1,000 ppb, will be prohibited – except where these brigades respond to industrial fires at facilities covered by European Parliament and Council Directive 2012/18/EU [44]. From 10 October 2029, the same restrictions will apply to fire-fighting foams and foam concentrates used in civil aviation. From 10 October 2026, PFHxA may no longer be placed on the market or used at the above concentrations in textiles, leather, furs, and hides, in clothing and related accessories for the general public, in footwear for the general public, in paper and cardboard materials intended to come into contact with food under the scope of Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 [45], in mixtures for the general public, and in cosmetic products as defined in Article 2(1)(a) of Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 [46].

In the area of human health protection, European Parliament and Council Directive 2020/2184 [47] was adopted at the EU level, which in Annex I, Part B, sets limit values for perfluorinated substances in water intended for human consumption. The limit values are established for the sum of 20 selected perfluorinated substances (0.1 µg/l) or for total PFAS, including the sum of all per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (0.5 µg/l). Member States are required to take the necessary measures to comply with the above limits by 12 January 2026. These substances are monitored when, following a risk assessment and management of catchment areas related to abstraction points carried out in accordance with Article 8 of the Directive, it is concluded that the presence of these substances in the water source is probable.

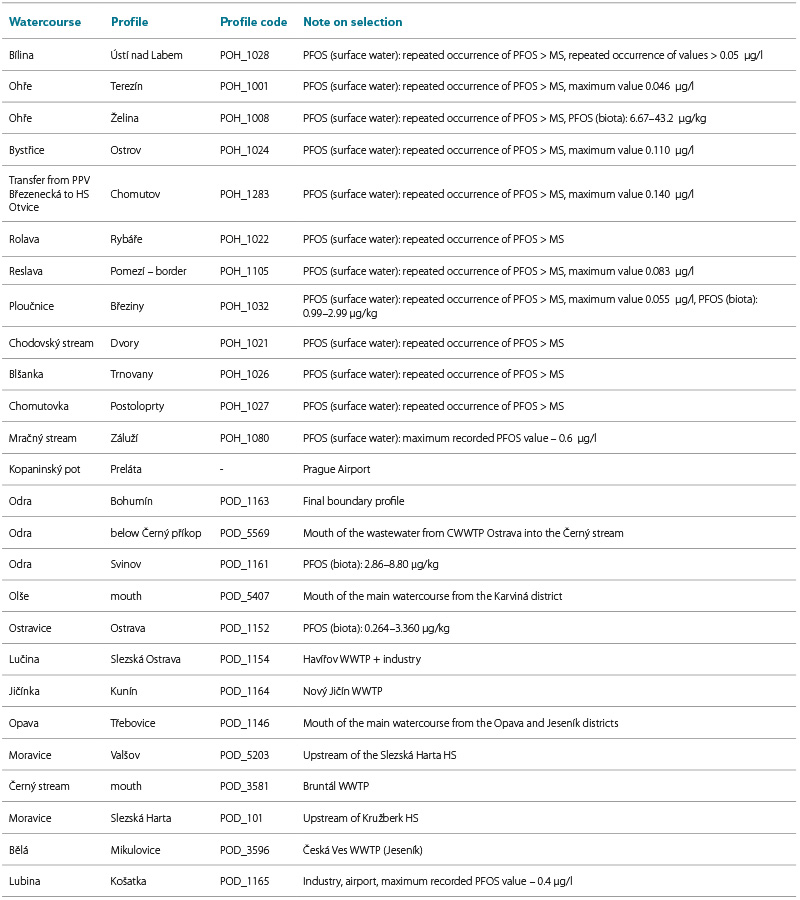

As of June 2024, the European Commission prepared an amendment to several EU water policy directives [48]. The amendment to European Parliament and Council Directive 2008/105/EC proposes a new list of priority substances for the aquatic environment, along with the corresponding environmental quality standards (EQS). Under number 65, a group of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) was listed, comprising 24 chemical perfluorinated compounds. For this sum of PFAS, an EQS has been set – annual average (EQS‑AA) of 0.0044 µg/l (4.4 ng/l) for the surface water matrix and 0.077 µg/kg wet weight for biota. In contrast to Directive 2020/2184, the amendment to Directive 2008/105/EC assigns a conversion factor for each PFAS relative to perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS = 1), against which the toxic risk of each additional PFAS is assessed. The analytically determined concentration of each PFAS is then multiplied by its respective factor, and the resulting sum is compared with the EQS. It should be noted that the PFAS lists in Directives 2020/2184 and 2008/105/EC do not fully overlap; 16 PFAS are common to both lists (Tab. 1).

Tab. 1. Comparison of lists of PFAS substances according to Directive 2020/2184 of the European Parliament and of the Council and the draft amendment of Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council

The draft amendments to the directives prepared by the European Commission were discussed in the European Parliament in autumn 2024. From January 2025 until early autumn, during the Polish and Danish Presidencies, a so-called trialogue took place between the Member States and the Council of the European Union, aimed at reaching a consensus on the legislative proposals for the amended water protection directives, including Directive 2008/105/EC. At the time of writing this article, the trialogue process had not yet been completed, but its conclusion was approaching. In the final stages of the trialogue, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) was also included in the PFAS sum. It has been found that this perfluorinated organic compound, with the shortest hydrocarbon chain, also exhibits persistence in the environment [49]. TFA concentrations in surface waters vary widely, ranging from a few to several hundred ng/l [50].

Environmental quality standards are also proposed in the amendment to European Parliament and Council Directive 2006/118/EC on the protection of groundwater against pollution and deterioration. In light of the latest scientific knowledge, Annex I of this Directive is supplemented with a quality standard for the sum of the four most problematic PFAS (PFHxS, PFOS, PFOA, PFNA) and TFA, in accordance with the value proposed by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). To account for differences in the toxicity of the four PFAS and TFA, relative potency factors are applied when calculating the sum of these five substances. The EQS is also 0.0044 µg/l (4.4 ng/l), the same as for surface water. The Directive notes that, in light of the latest scientific knowledge, it is important that the parameters for PFAS, including TFA, set out in Directive 2020/2184/EC be reviewed and, if necessary, revised in the near future, and that any such revisions be harmonised with the EQS set out in Annex I of Directive 2006/118/EC. Legislative approval of the amended directives is expected by the end of 2025.

Within the EU, there is also an ongoing intensive discussion on how to harmonise EQS for PFAS across surface water, groundwater, and water intended for human consumption, which will be important for the further development of legislative instruments. It is also noted that the current EQS cover only selected PFAS, even though many more (potentially several thousand) are present in the aquatic environment. For these reasons, the European Commission is preparing to establish EQS for the total PFAS load in surface waters. This is expected to take place during the next review of Directive 2008/105/EC. As part of the documentation for the review, six proposals for addressing total PFAS have been prepared [51]. The greatest consensus currently exists around the proposal setting an annual average EQS-RP of 0.05 µg/l of total organic fluorine for surface waters. The Joint Research Centre (Italy) proposes measuring total organic fluorine, or “total PFAS”, only if the corresponding EQS for the sum of 24 PFAS (for both surface waters and biota) has been met (not exceeded).

The relative potency factor (RPF) is used in the risk assessment of mixtures of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances to express their potential harmfulness relative to a specific index compound, typically PFOA, for a given health-relevant endpoint. By assigning an RPF of 1 to the index compound, the equivalent exposure of any PFAS in the mixture can be calculated as “PFOA equivalents.” This allows for a more accurate assessment of the cumulative health risk posed by multiple PFAS, which often co-occur in environmental contamination.

The requirements of Directive 2008/105/EC, as amended by Directive 2013/39/EU, have been transposed into national legislation on the protection of surface waters through Government Regulation No 401/2015 Coll. [52]. Currently, environmental quality standards have been established only for PFOS, set at 6.5 ∙ 10-4 µg/l (annual average EQS) and 36 µg/l as the maximum allowable concentration.

The amended Decree No. 428/2001 Coll. [53] already incorporates a quality limit for raw surface water (intended for treatment to drinking water) for the sum of 20 PFAS in accordance with European Parliament and Council Directive 2020/2184 (0.1 µg/l) for all three categories of raw water treatment: A1, A2, and A3.

An overview of analytical methods for PFAS determination

A range of analytical methods has been developed for PFAS monitoring, enabling their determination at sub‑nanogram levels. Most methods employ liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometric detection. They mainly differ in the sample preparation approach – direct injection, online and offline solid-phase extraction (SPE), or dispersive magnetic solid-phase extraction (DMSPE) are all possible. The method applied for analysing water at the inlet and outlet of a drinking water treatment plant in Catalonia is based on the direct injection of 900 µl of sample without any prior preparation [54]. A similar method, also based on the direct injection of 100 µl of centrifuged water sample without any further preparation, using UHPLC‑MS/MS for the analysis of several perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAA) across a wide range of water matrices, demonstrated high sensitivity (sub‑nanogram quantification), speed, accuracy, and low matrix effects [55]. A direct injection method of 150 µl of water sample using an Agilent 1100 HPLC coupled to a Waters Quattro Micro tandem mass spectrometer is described in a study analysing both water and soil samples [56]. Another analytical method applicable for the determination of these contaminants is based on solid-phase extraction (SPE) followed by gas chromatography with negative chemical ionisation and mass spectrometric detection. The method is highly sensitive, and the results are fully comparable with those obtained using HPLC–MS/MS. Using this method, surface water samples from the Vltava and Elbe rivers were tested, and the target substances were detected in all samples [57]. A further review study [58] is devoted to analytical methods for PFAS determination developed and applied between 2018 and 2023. For PFAS extraction, solid-phase extraction is most commonly used, followed primarily by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry for quantification [58]. A solid-phase extraction method using 100 ml of water sample was applied to determine 22 PFAS in drinking water in the Czech Republic. High-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometric detection was used for the actual analysis. Using this method, 67 tap water samples and 31 bottled water samples were analysed. PFAS intake by an adult from tap or bottled water amounted to a few per cent of the tolerable weekly intake established by the European Food Safety Authority and therefore did not represent a significant risk [59].

Another direct injection method for the analysis of PFAS in environmental water samples uses centrifugation and membrane filtration of small sample volumes, which are then analysed by UHPLC‑ESI‑MS/MS using a delay column to reduce interference from background PFAS contamination. For the actual analysis,

an AB Sciex 6500 plus Q‑Trap mass spectrometer is used, operated in negative multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. The instrument system includes a delay column positioned between the pumps and the autosampler to reduce interference from background PFAS. The method monitors eight short‑ and long‑chain PFAS, which are identified by tracking specific precursor–product ion pairs and their retention times, and quantified using calibration curves based on isotopically labelled internal standards. The method is technically robust and provides sufficient sensitivity and reproducibility for use as a primary screening approach to detect and quantify PFAS at levels typically observed in surface and drinking waters. It can accurately detect and quantify common PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS, at concentrations below the commonly recommended screening level of 70 ng/l [60].

Another study [61] addresses the determination of PFAS in accordance with Directive 2020/2184/EU using the prescribed methods. In this paper, three different methods were developed and evaluated for the determination of 20 PFAS in tap and bottled water, based on online and offline solid-phase extraction (SPE) and direct injection. In all cases, ultra‑high‑performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC‑MS/MS) was used as the analytical technique. Offline SPE using Oasis Weak Anion Exchange (WAX) cartridges provided the best performance in terms of quantification limits (LOQ ≤ 0.3 ng/l) and accuracy (R ≥ 70 %) in drinking water samples. Online SPE and direct injection had certain drawbacks, such as background contamination issues and lower accuracy for the least polar compounds. The offline method was applied to the analysis of 46 drinking water samples, including 11 commercial bottled samples, 23 Spanish tap water samples, and 12 international tap water samples [61].

In Greece, a method combining ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Orbitrap-MS), using an electrospray ionisation (ESI) interface in negative mode, was developed, validated and applied to real samples. Samples of lake and seawater, as well as wastewater from municipal and hospital WWTPs, were analysed. The concentrations in surface waters were below the limit of detection or significantly lower than those in wastewater [62].

Another emerging method aimed at accelerating and simplifying PFAS determination applies dispersive magnetic solid-phase extraction (DMSPE) to enrich PFAS in various surface water samples. For the preconcentration and extraction of PFAS from various river water samples, magnetic Fe₃O₄ @ MIL-101 (Cr) was used for the first time as an adsorbent in MSPE. Concentrations of the target analytes in the water samples were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography with a diode-array detector and ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography – tandem mass spectrometry [63].

To assess PFAS contamination levels in sludge originating from selected PFAS at 43 WWTPs in the Czech Republic, an analytical screening method was developed and validated for 32 PFAS representatives, including new substitutes (e.g. GenX, sodium dodecafluoro-3H-4-oxanonanoate, 8-dioxanonanoate – NaDONA). For the risk assessment of agricultural use of WWTP sludge commonly applied as fertiliser, human exposure to PFAS was calculated for various types of vegetables grown in soil potentially fertilised with realistically contaminated sludge in the Czech Republic [64].

A method for the quantitative determination of PFOS was also developed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with Orbitrap mass spectrometry (Orbitrap-MS), employing a heated electrospray ionisation (HESI) interface operated in negative mode. HPLC separation of the analytes was achieved using a reversed-phase C18 analytical column (RP-C18). The method enables reliable monitoring of PFOS and its derivatives in environmental samples in accordance with the criteria of the environmental quality standard, taking into account the maximum permissible concentrations and the annual average concentrations specified in Directive 2013/39/EU. The method was applied for the routine analysis of selected PFAS in environmental samples from the Baltic Sea region [65].

A non-target screening (NTS) approach based on high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) is also essential for the comprehensive characterisation of PFAS in environmental, biological, and technical samples, due to the very limited availability of authentic PFAS reference standards. Since MS/MS information is not always achievable in trace analysis and only selected PFAS are present within homologous series, additional techniques for prioritising HRMS-measured data according to their probability of being PFAS are highly desirable. The procedure proposed in the study could also be applied to the monitoring of other groups of compounds [66].

Given the approaching obligation to regularly monitor the concentrations of selected PFAS, methods enabling highly sensitive analysis for the routine determination of PFAS in various types of water (drinking water, surface water, and groundwater) are being developed rapidly [67, 68]. Simultaneously, methods for the quantification of short-chain and ultra-short-chain PFAS are being developed [69].

Due to the fact that there is a very large number of PFAS and it is rather demanding to identify or quantify all of them in a sample, simpler methods for determining total organic fluorine are increasingly being adopted for screening purposes. The most commonly used method for this purpose is the determination of adsorbable organic fluorine (AOF), which provides non-specific information on the amount of organofluorine compounds. A procedure using combustion ion chromatography (CIC) covers a wide range of organofluorine compounds that are currently not detectable by LC-MS/MS. AOF is important for estimating unknown PFAS concentrations, screening PFAS contamination, and assessing PFAS exposure [70, 71].

As noted above, the number of publications addressing PFAS is enormous. The main challenges that must be addressed when analysing PFAS are high background levels, which require strictly followed procedures at the very stage of sample collection, and the careful selection of suitable sampling containers and other tools used during sample processing. Given the very strict environmental quality standards proposed in European legislation, methods for determining PFAS are highly demanding in terms of instrumentation. Due to their widespread presence, background levels of the target compounds can be high even in standard laboratory equipment. Some components of analytical instruments also need to be replaced with PFAS-free equivalents.

Sampling

Due to the ubiquitous presence of PFAS, even the simple act of sampling is complicated, including the choice of materials for the sample containers. The influence of storage and sample preparation conditions – such as storage duration, solvent composition, storage temperature (4 °C and 20 °C), and sample mixing technique (shaking or centrifugation) – on PFAS losses into container materials was studied for commonly used HDPE materials, including polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polypropylene copolymer (PPCO), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), and glass. The highest losses of long-chain PFAS in aqueous solutions were observed with polypropylene. Sorptive losses of long-chain PFAS decreased in an 80 : 20 water : methanol solution (%, v/v). Sorption losses of PFAS with temperature were dependent on the solvent composition [72]. When sampling for these compounds, strict procedures must be followed to prevent secondary contamination. Sampling equipment and accessories must not contain materials such as PTFE, PVDF, PCTFE, ETFE, or FEP (e.g., commercial brands Teflon®, Hostaflon®, Kynar®, Neoflon®, Tefzel®). LDPE must not be used in direct contact with the sample medium (e.g., for sample containers) but may be present in, e.g., protective bags. HDPE is most commonly used for sample containers and should be pre-tested for the presence of PFAS.

Field clothing and footwear used by sampling personnel must not contain Gore-Tex® or other waterproof materials, nor materials with stain-repellent surface treatments. Suitable clothing and footwear include items made of cotton, PVC, or polyurethane that have been repeatedly washed beforehand without synthetic softeners. PFAS may also be present in a wide range of personal care products, including cosmetics, creams, shampoos, repellents, etc. Therefore, it is recommended not to apply such products on the day of sampling or during sampling activities, in order to avoid any contact between these products and the sampling equipment and materials. Provided that all other principles are observed, these products may be used before sampling work begins, but their application in the field during sampling (for example, sunscreens or insect repellents) should be avoided. The basic precaution is thorough hand washing and the use of powder-free nitrile gloves.

Sample contamination may also occur during transport. It is therefore essential to avoid all of the above-mentioned materials, water-repellent labels on sample containers, and permanent markers. To check for possible contamination during sampling and transport, field blanks and transport blanks are collected [73].

Current monitoring of PFAS in surface waters in the Czech Republic

Substances from the PFAS group are not yet monitored systematically across the entire Czech Republic. An analysis was carried out of the available monitoring data for individual substances from this group obtained from the river basin authorities, which conducted monitoring of surface water quality. When calculating average values (annual averages or overall averages for the period during which PFAS compounds were monitored), values below the limit of quantification (LOQ) were included at the LOQ level.

In the Ohře river basin, PFOS was measured annually from 2012 to 2023 at 42–110 profiles. During 2012–2017, the limit of quantification (LOQ) was 0.010 µg/l, and from 2018 onward it was 0.020 µg/l. Throughout the entire monitoring period, the majority of measurements were below the LOQ, ranging from 70 % to 100 % in individual years. Positive values therefore ranged from 0 % to 30 % in individual years. Overall, 83 % of measurements were below 0.020 µg/l, 16 % were between 0.020 and 0.100 µg/l, and 2 % exceeded 0.100 µg/l, with the maximum recorded value reaching 0.600 µg/l. The annual mean values evaluated for the entire basin ranged from 0.010 to 0.021 µg/l in individual years, with an overall mean of 0.017 µg/l for the entire period. In 2024, monitoring of PFAS in the Ohře basin was initiated in accordance with Directive 2020/2184 on the quality of water intended for human consumption in drinking water reservoirs. The LOQ used was 0.006 µg/l for PFBA and 0.001 µg/l for all other PFAS. Only a few values above the LOQ were detected for PFPeA, PFHxA, PFHpA, PFOA, PFDA, PFTrDA, PFBS, PFHpS, PFOS, PFDS, and PFTrDS, ranging from 0.001 to 0.014 µg/l.

In the Odra river basin, only PFOS was measured at 80–82 river network profiles during 2017–2023, with a LOQ of 0.100 µg/l from 2017 to 2021, which was lowered to 0.010 µg/l in 2022. Over the entire monitoring period, only two positive values were recorded (0.210 and 0.400 µg/l in 2018). Annual mean values evaluated for the whole basin ranged from 0.010 to 0.101 µg/l, with a mean of 0.075 µg/l for the entire period.

In the Morava river basin, PFOS and PFOA were monitored during 2013–2023 at 44–100 profiles. The LOQ for PFOS was 0.020 µg/l in 2013–2019, 0.010 µg/l in 2020–2022, and 0.6 ng/l from 2023. Throughout the entire evaluated period, values below LOQ predominated. The proportion of positive values in individual years up to 2022 was only 0–2 %. Overall, 99.5 % of values were below 0.020 µg/l, 0.4 % were in the range 0.020–0.100 µg/l, 0.1 % were above 0.100 µg/l, and the maximum recorded value was 3.65 µg/l. Annual mean values calculated for the entire basin ranged from 0.0006 to 0.021 µg/l in individual years, with an overall average of 0.016 µg/l. Since 2023, when the LOQ was lowered to 0.6 ng/l, approximately 10 % of results have exceeded the LOQ.

For PFOA, the LOQ used throughout the entire period was 0.010 µg/l. Over the entire evaluated period, values below the LOQ predominated. In individual years up to 2022, only 0–2 % of values were positive. Overall, 99.6 % of values were below 0.010 µg/l, 0.3 % of values ranged from 0.010–0.100 µg/l, and 0.1 % of values were above 0.100 µg/l, with the maximum recorded value being 1.8 µg/l. Annual mean values, calculated for the entire catchment, ranged from 0.010–0.014 µg/l in individual years, with an overall mean of 0.011 µg/l. In 2024, monitoring of PFAS was initiated at 27 selected profiles in the Morava basin, covering the scope of Directive 2020/2184 on the quality of water intended for human consumption and the proposed amendment to European Parliament and Council Directive 2008/105/EC. The applied LOQs for individual substances ranged from 0.018 to 1.0 ng/l. In addition to PFOS and PFOA, PFBA, PFPeA, PFHxA, PFHpA, PFNA, PFDA, PFUnDA, PFBS, and PFHxS were also detected above the LOQ, in the range of 0.02–12.6 ng/l.

In the Elbe river basin, PFOS and PFOA were monitored annually from 2012 to 2024 at 20–130 profiles. The LOQ for PFOS was 0.020 µg/l in 2012–2015, 0.002 µg/l in 2016–2017, and 1 ng/l from 2018 onwards. Throughout the entire monitoring period, values below the LOQ predominated, accounting for approximately 70 % overall, with 96.5 % of values below 0.020 µg/l, 3.2 % ranging from 0.020 to 0.100 µg/l, 0.3 % exceeding 0.100 µg/l, and the maximum recorded value 0.568 µg/l. The annual mean values calculated for the entire basin ranged from 0.0013 to 0.031 µg/l in individual years, with a mean of 0.0054 µg/l for the entire period.

For PFOA, the LOQ was 0.020 µg/l in 2012–2015, 0.005 µg/l in 2016–2023, and 1 ng/l from 2018 onwards. Throughout the monitored period, values below the LOQ predominated, accounting for about 95 %. Overall, 99.6 % of the values were below 0.020 µg/l, 0.4 % were in the range 0.020–0.100 µg/l, and the maximum recorded value was 0.046 µg/l. Annual mean values (evaluated for the entire basin) ranged from 0.0025 to 0.020 µg/l in individual years, with an overall mean of 0.0063 µg/l. Broader PFAS monitoring in this catchment started in 2025.

In the Vltava river basin, PFOS and PFOA were monitored on 28–134 profiles during 2012–2024. The LOQ for PFOS was 0.100 µg/l in 2012–2013, 0.005 µg/l in 2014–2021, 0.003 µg/l in 2022, and 0.5 ng/l from 2023 onwards. Throughout the entire monitoring period, values below the LOQ prevailed. Positive values in individual years ranged from 0 % to 26 %. Overall, 87 % of values were below 0.020 µg/l, 12.9 % were between 0.020 and 0.100 µg/l, 0.1 % were above 0.100 µg/l, and the maximum recorded value was 0.289 µg/l. Annual mean values evaluated for the entire basin ranged from 0.0022 to 0.100 µg/l in individual years, with an overall average of 0.017 µg/l. Since 2023, when LOQ was lowered to 0.5 ng/l, approximately 20 % of results have exceeded the LOQ.

For PFOA, the LOQ was 0.100 µg/l in 2012–2013, 0.010 µg/l in 2014–2021, 0.005 µg/l in 2022, and 2 ng/l from 2023 onwards. Throughout the entire monitoring period, values below the LOQ predominated. Positive values in individual years ranged from only 0 % to 22 %. Overall, 87.4 % of values were below 0.010 µg/l, 12.6 % were in the range 0.010–0.100 µg/l, and only a single value exceeded 0.100 µg/l, with the maximum recorded value being 0.111 µg/l. The annual mean values for the entire basin ranged from 0.0022 to 0.100 µg/l in individual years, with an overall mean of 0.020 µg/l. In 2023, PFAS monitoring in line with Directive 2020/2184 on the quality of water intended for human consumption was initiated at 42 selected profiles in the Vltava basin, and from 2024 it was extended to include four additional substances. The applied LOQ for individual substances ranged from 0.5 to 6.0 ng/l. In addition to PFOS and PFOA, PFBA, PFBS, PFHxS, PFHpA, PFHxA, PFOS-H4, and PFTrDA were detected above the LOQ in the range of 1.2–55 ng/l. Further details on the monitoring of these substances in the Vltava basin are provided in [74].

The values detected in surface waters in the Czech Republic can be compared with findings of PFAS compounds in other countries. Between 2004 and 2010, surface water samples from 41 cities across 15 countries were analysed. PFOS and PFOA were present in all samples, with average concentrations ranging from non-detectable (ND) to 0.070 µg/l for PFOS and 0.0002–1.630 µg/l for PFOA. The maximum average PFOS concentration in surface waters in the United Kingdom was 0.019 µg/l. The PFOA concentration in surface waters in Osaka reached 1.630 µg/l. In the other cities included in the study, average PFOA concentrations were generally below 0.100 µg/l. In surface water from the Júcar River, PFAS were detected at concentrations ranging from 0.04 ng/l to 0.0831 µg/l. In Sweden, average concentrations of 26 PFAS were found in samples collected from drinking water source areas at 0.0084 µg/l, in surface waters at 0.112 µg/l, and in groundwater at 0.049 µg/l. In surface waters of the Rhine river basin, from Lake Constance to the North Sea, the concentrations of 40 PFAS were examined to assess the impact of both point and diffuse sources. Among the PFAS, perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) predominated with concentrations up to 0.181 µg/l, and perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) with concentrations up to 0.335 µg/l. These two compounds accounted for up to 94 % of the total PFAS [24].

Pilot extension of monitoring to additional profiles

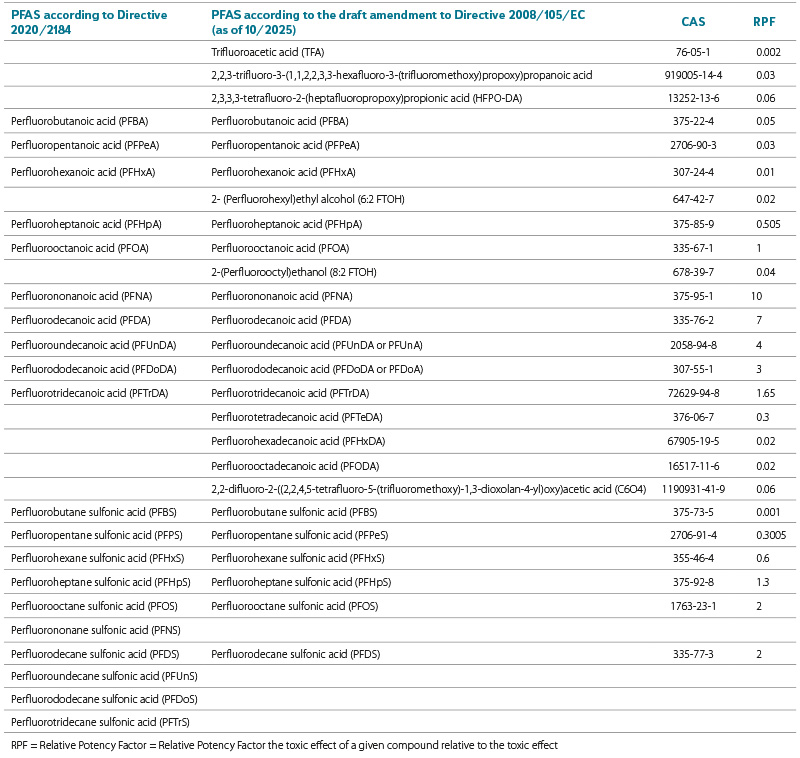

To supplement the monitoring profiles of PFAS substances on a broader scale, pilot monitoring was proposed in the Ohře and Odra river basins. In collaboration with the river basin administrators major closing profiles and sites with repeated PFOS detections above the limit of quantification were selected. These profiles are listed in Tab. 2. In addition to the sites in the target river basins, the Kopaninský stream on the outskirts of Prague was included, as it is strongly affected by Václav Havel Airport.

Tab. 2. Selected sampling profiles

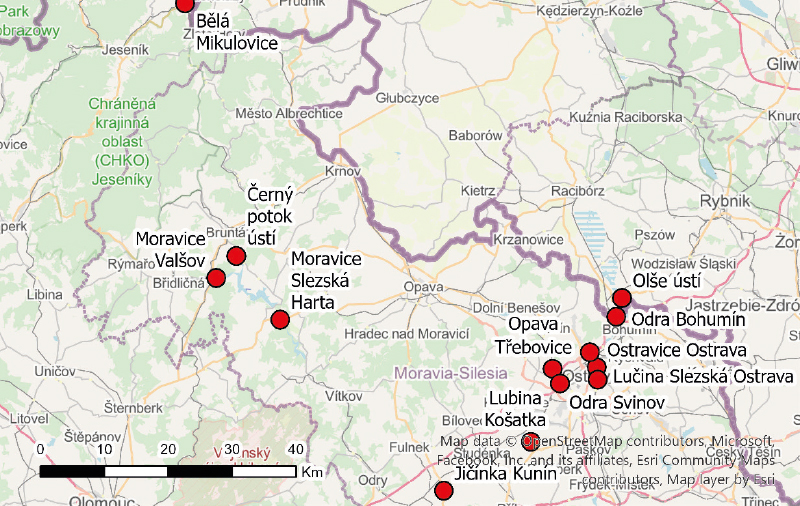

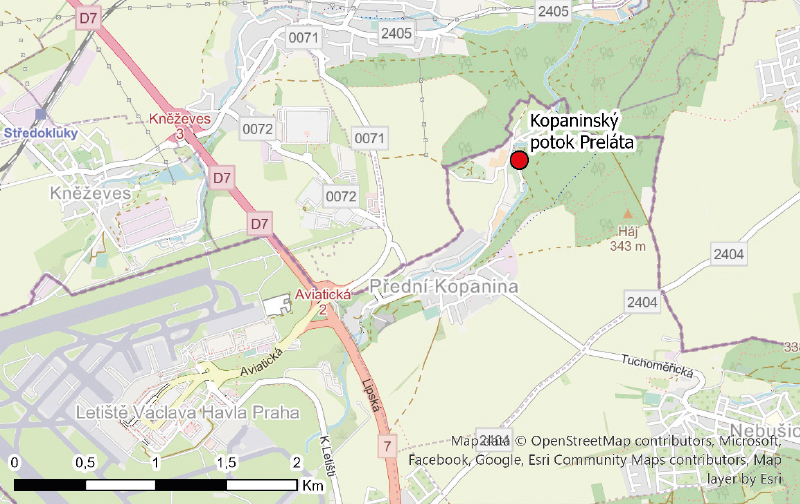

A summary of the monitoring sites in the Ohře basin is shown in Fig. 1, the sites sampled in the Odra basin are presented in Fig. 2, and Fig. 3 shows the sampling site on the Kopaninský stream.

Fig. 1. Location map of Ohře basin profiles

Fig. 2. Location map of Odra basin profiles

Fig. 3. Location of the sampling profile on the Kopaninský stream

The sampling also includes the measurement of field parameters: air temperature, water temperature, and water electrical conductivity. At profiles where it is possible, the flow is recorded at the nearest gauging station.

ANALYTICAL METHODS USED FOR THE DETERMINATION AND IDENTIFICATION OF PFAS

Target analysis

In developing the method for determining PFAS in surface water, we based our approach on published methods that employed similar instrumentation [67, 68]. A liquid chromatography method with mass spectrometric detection under negative electrospray ionization conditions was selected. Methanolic standard solutions were purchased from Neochema and Altium International, as well as internal standards from Wellington Laboratories, and instrument accessories for PFAS analysis.

Analyses were carried out on an Exion LC/SCIEX liquid chromatograph coupled with a Triple Quad™ 7500 mass spectrometer using negative-mode electrospray ionization, Q0D optimization, and simple mode for the analysis. For analyte separation, a delay column Phenomenex Luna Omega C18, 100 Å, 50 × 2.1 mm, 1.6 µm, and an analytical column Phenomenex Luna Omega PS C18, 100 Å, 100 × 3.0 mm, 3 µm, were used. For the gradient elution of analytes, mobile phase A (20 mM ammonium acetate in water) and mobile phase B (methanol) were used. The mobile phase flow rate was 0.6 ml/min. The initial concentration of mobile phase A was 90 %, decreasing to 45 % at 0.1 min. From 4.50 min to 4.95 min, the concentration of mobile phase A was 1 %, returning to 90 % at 5.0 min. This gradient was used for PFAS with shorter chains.

Long-chain PFAS such as PFHxDA and PFODA are more hydrophobic than short-chain PFAS and appear to bind to polypropylene containers when the methanol concentration is below 40 %. For these compounds, the method had to be adjusted, and the gradient elution conditions were modified. The initial concentration of mobile phase A was 90 %, decreasing to 35 % at 1.5 min. At 8 min, the concentration of phase A was 5 %. From 8.1 min to 12.0 min, the concentration of mobile phase A was 1 %, rising to 90 % at 12.5 min. Calibration with the internal standard was prepared over the range 1–200 ng/l.

Sample preparation is performed as follows: 1 ml of the water sample is added to a 2 ml glass vial containing 0.65 ml of a mixed methanolic solution of surrogate standards (resulting in a concentration of 50 ng/l for each standard). The final MeOH concentration in the diluted sample is 40 %, and standards, blanks, and control samples are prepared with the same methanol concentration. The volume of sample injected is 100 µ/l.

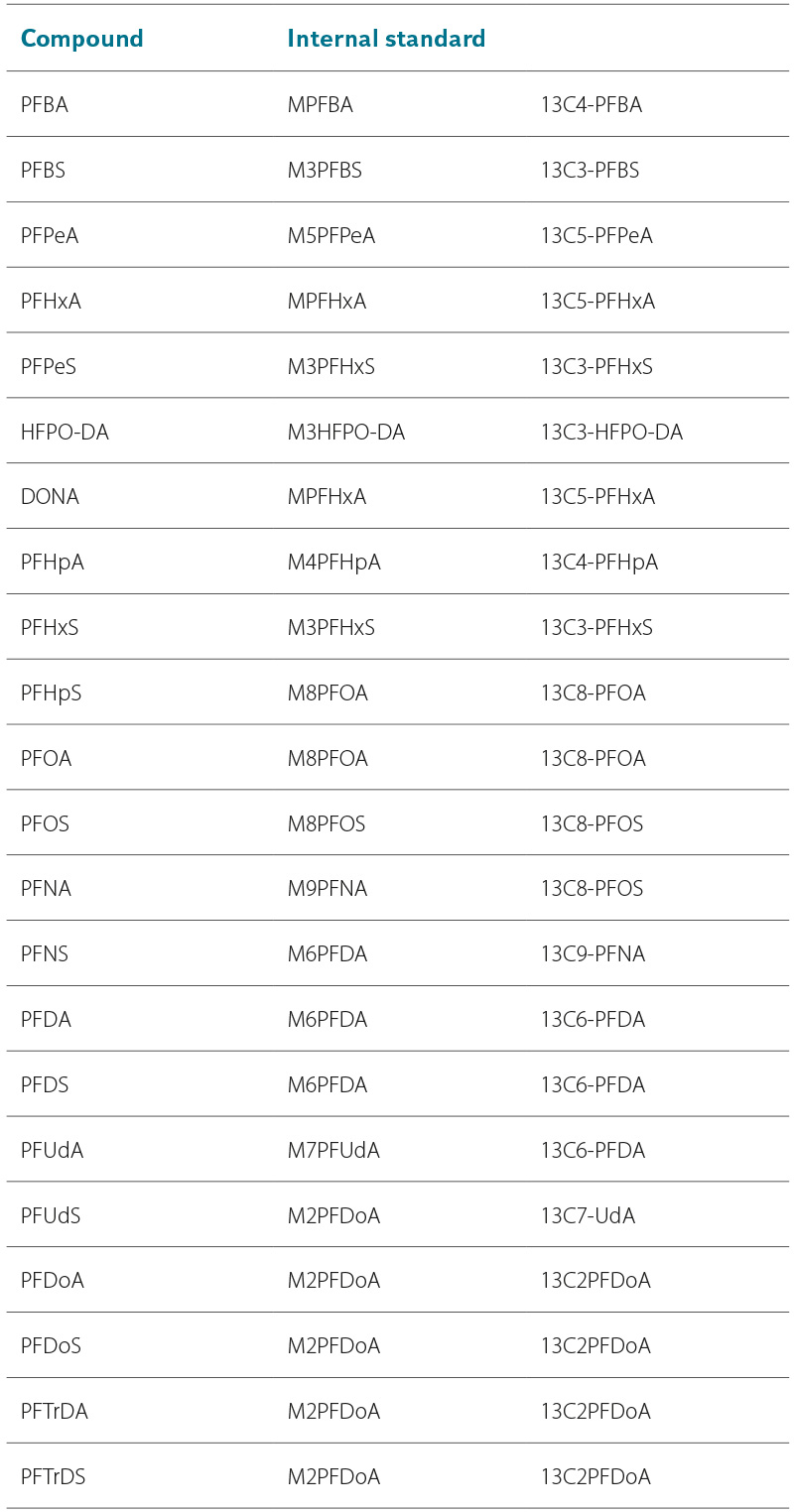

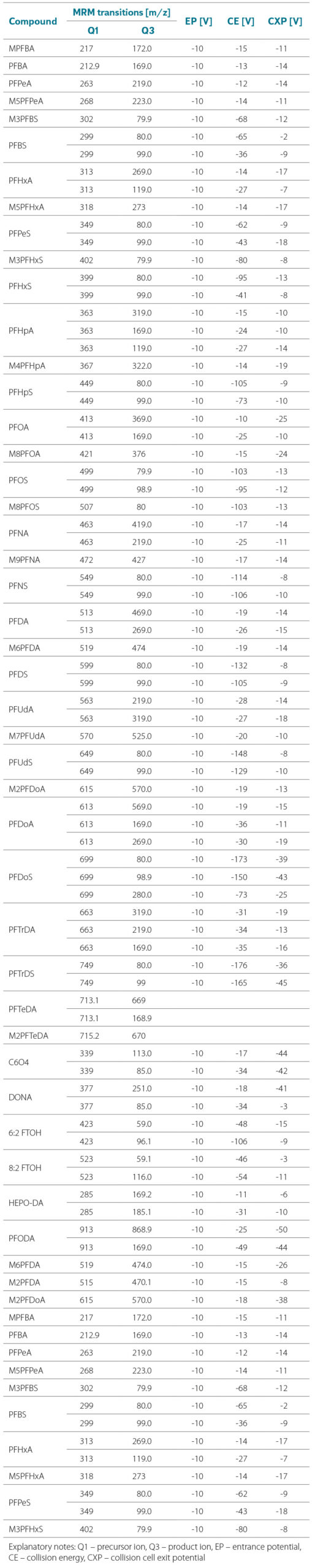

Optimal chromatographic conditions were tuned for each individual PFAS. For each analyte, two characteristic transitions are monitored, one of which is for the internal standard. Tab. 3 provides an overview and characteristics of the internal standards assigned to each analyte. The measured MRM transitions are listed in Tab. 4. The method is ready for testing with analytical standards.

Tab. 3. Internal standards

Tab. 4. Selected diagnostic ions

Non-target analysis

For the development of a non-targeted analysis method focused on PFAS, high-resolution liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry and electrospray ionization in negative mode was chosen.

Analyses were performed on an Agilent 1290 Infinity II liquid chromatograph coupled with a SCIEX X500R QTOF mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization in negative mode. In the first phase, a universal method for non-targeted analysis using ammonium formate as the mobile phase was tested. For PFAS, ammonium acetate was ultimately chosen as the mobile phase. For the separation of analytes, an Arion Plus C18 analytical column (100 × 2.1 mm, 3 µm) was used. Mobile phase A is 5 mM ammonium acetate, and mobile phase B is methanol. The gradient starts at 95 % A for 0.5 min and decreases to 5 % A by 14 min, where it is held for 4 min. At 18.1 min, the concentration of A is raised back to 95 %. From 18.1 min to 22 min, the concentration of A is maintained at 95 %. The column temperature is 30 °C, and the mobile phase flow rate is 0.2 ml/min. The injection volume is 100 µl. Compounds are analysed using electrospray ionisation in negative mode (ESI–) combining a full scan over the mass range 70–1 200 Da with data-independent acquisition. The spray voltage is −4,500 V, the collision energy −35 V, and the declustering potential −80 V for all compounds. Compound identification is performed using a spectral library.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are currently receiving considerable attention. These substances, due to their chemical properties, widespread use across various industrial sectors, environmental persistence, long-term bioaccumulation potential, and the associated risks to human health, raise significant concern. The article summarizes the legislative requirements for monitoring PFAS in the EU and the Czech Republic, including the lists of substances according to European Parliament and Council Directive 2020/2184 and the proposed amendment to Directive 2008/105/EC. Based on data provided by the individual River Basin Authorities, an analysis of the current status of PFAS monitoring in surface waters in the Czech Republic was carried out. The determination of these substances is analytically demanding and requires the implementation of new methodologies, including instrumental equipment. In the individual river basins, these substances are monitored to varying extents and with differing sensitivity. Until 2022, only PFOS, as well as PFOA (except for the Odra and Ohře basins) were systematically monitored in surface waters in the Czech Republic. However, due to the different LOQ used in individual river basins in previous years, when most results were lower than the stated LOQ, the nature of the data does not allow for an objective assessment of the situation throughout the Czech Republic. With the expansion of analytical capabilities, methods are gradually being introduced that enable the determination of individual compounds with higher sensitivity and, in particular, a wider range of PFAS substances monitored. Since 2023, monitoring of PFAS has also started in individual river basins in accordance with the requirements of Directive 2020/2184 on the quality of water intended for human consumption and, where applicable, in accordance with the proposed amendment to Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, including the pilot monitoring by TGM WRI described in the article. Following the final approval of the amendment to Directive 2008/105/EC, there will be a need to transpose the new environmental quality standards for PFAS into Government Regulation No. 401/2015 Coll. According to the latest status of the discussions (in September 2025), the transposition deadline is expected to be 21 December 2027. By the same date, Member States shall establish a supplementary monitoring program for PFAS (including other newly identified priority substances) and, by 22 December 2030, a preliminary programme of measures concerning these substances.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of Project no. SS07010208 Research on the Identification and Quantification of Selected PFAS in Surface Waters (PFAS-SW), funded by the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (TA CR) under the Programme of Applied Research, Experimental Development, and Innovations in the Field of the Environment – Environment for Life, Subprogramme 1 – Operational Research in the Public Interest. Important information for the project was provided by the cooperating state enterprises Ohře Basin, Odra Basin, Vltava Basin, Elbe Basin, and Morava Basin Authorities.

The Czech version of this article was peer-reviewed, the English version was translated from the Czech original by Environmental Translation Ltd.