ABSTRACT

The presented article addresses current problems in food waste management and prevention at the municipal level in the Czech Republic. It summarises the authors’ team’s knowledge within the framework of long-term solutions to this issue, presents a diverse range of preventive measures, conducts an elementary economic analysis of municipal expenditures and revenues in waste management, and points out current problems and pitfalls for development in the coming years. The most important ones include the growing obligations of municipalities in preventing the creation and management of municipal waste and the associated increasing pressure on staffing the circular economy and waste management agenda, insufficient capacities for food waste management in the near future (with the planned fulfilment of national goals), an inadequate system of transmission and exchange of relevant information, and the ever-recurring indiscipline of citizens in primary waste sorting.

INTRODUCTION

Food waste generation represents a significant environmental, economic and socio-ethical challenge. At both international and national levels, this issue has received increasing attention, as it is closely linked to the efficient use of natural resources as well as to the principles of the circular economy and food security. On the one hand, these include wastes that, through appropriate separation, can provide a valuable raw material source, for example for composting or biogas production (instead of ending up in landfills), and, on the other hand, food products that are still fit for consumption but, for various reasons, are not used and become waste. Food waste is generated at all stages of the complex food supply chain – starting with primary production, where losses occur due to weather conditions, pest infestations, or failure to meet market standards for shape and size, through the processing industry, distribution and retail, and finally to end consumers (including households, restaurants, school canteens, and other public catering facilities) where the share of waste generation is often the highest [1]. From the perspective of the agri-food sector, the issue of food waste therefore affects a wide range of different areas and represents an interdisciplinary matter involving the competencies of several ministries of the Czech Republic.

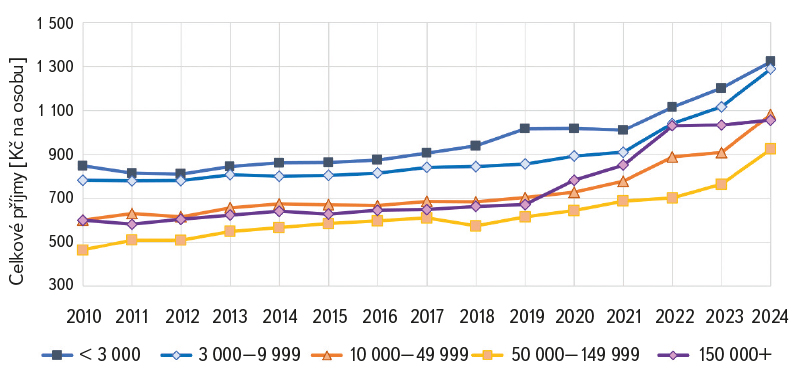

In the European Union, households are identified as the largest producers of this type of waste, accounting, according to estimates, for more than 50 % of the total volume of food waste [2] (Fig. 1). This is mainly due to poor shopping planning, improper food storage, misunderstanding of the labelling “best before” and “use by”, inappropriate portion sizes during cooking, and other factors such as, for example, reluctance to make use of leftover food. Another significant share of food waste is generated in public catering facilities. A substantial proportion of this waste consists of food that would still be edible and usable. Such food is often discarded for reasons of convenience, lack of time, low awareness of environmental impacts, or due to organisational and operational constraints.

Fig. 1. Food waste production in the European Union at each stage of the food chain in 2023 [2]

Household food waste burdens not only household budgets but also the environment. The impacts are significant:

- Environmental – natural resources (water, energy, land, and human labour) are consumed unnecessarily. It is estimated that the global carbon footprint of food waste accounts for approximately 8–10 % of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions [3]. In addition, food waste disposed of in landfills generates methane, a gas with a significantly higher global warming potential than carbon dioxide.

- Economic – for households, discarded food represents a direct financial loss. At the macroeconomic level, it constitutes a loss of value across the entire supply chain and increased costs for municipalities related to waste management.

- Socio-ethical – in a global context, where hundreds of millions of people suffer from undernutrition and food insecurity, massive waste represents a serious ethical paradox: while some of the population experiences food insecurity, a substantial amount of food prepared for consumption goes unused.

For the sustainable and circular-economy-compliant management of already generated food waste, as well as the practical implementation of measures to prevent its generation, it is necessary to provide expert support to municipalities in the Czech Republic. Increasing responsibilities in the areas of circular economy and waste management are being transferred to them, and for many, navigating this environment is becoming complex and, in the long term, unmanageable. The provision of methodological, data-driven and technical support to cities and municipalities in the Czech Republic is essential to achieving national and European targets for reducing food waste and to enabling a successful transition to a more sustainable model of resource management [4].

METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURE

The methodological approach to addressing preventive measures for reducing food waste at the municipal level was based on current strategic documents in the fields of circular economy and waste management, on the results of previous research projects conducted by the authors’ team, and on a review of relevant outputs from research projects carried out by other organisations, as well as practical experience.

Strategic documents

At the international level, the key document is the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, specifically Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.3, which aims to halve per capita global food waste by 2030. To support its implementation, the Champions 12.3 initiative was established, bringing together governments, businesses, and non-profit organisations.

At the European level, the issue has become a priority within the Circular Economy Action Plan. The key legislative framework is provided by the revised Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council [5], which amends the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC). This amendment requires Member States to adopt specific food waste prevention programmes and sets a target to reduce food waste by 50 % by 2030, in line with SDG 12.3 of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. To ensure comparable data across the EU, Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1597 [6] was adopted, defining a uniform methodology for measuring food waste. Scientific knowledge on food waste has been further advanced through projects such as FUSIONS and REFRESH, funded under the Horizon 2020 programme [7, 8]. Both projects delivered methodologies for measuring food waste, prevention scenarios, and policy recommendations. Current European initiatives build on these findings, including support for food redistribution and waste taxation.

The Czech Republic has implemented the European requirements on food waste into its national legislation and strategic documents. A key instrument is the Czech Waste Management Plan for 2025–2035, which in Chapter 3.4 includes the Food Waste Prevention Programme [4]. This programme defines three specific national targets:

- Prevent the generation of food waste and reduce its production in primary production, food processing, distribution, and consumption.

- By the end of 2030, reduce food waste generated during processing and production by 10 % compared with the amount produced in 2020.

- By the end of 2030, reduce per capita food waste in retail and other food distribution channels, in restaurants and catering services, and in households by 30 % compared with the amount produced in 2020.

In summary, the legislative and strategic framework at the EU level is now relatively robust. The Czech Republic transposes these requirements into national policy and research activities; however, a comprehensive and detailed strategy is still lacking – one that would more effectively integrate the various actors across the food supply chain and provide municipalities with concrete, data-driven tools to achieve the established targets. In the future, it will therefore be essential to strengthen inter-ministerial cooperation, expand targeted measures at the level of municipalities, schools, and food facilities, and establish a reliable system for data sharing and monitoring.

Research results and experience from practice

For the development of concrete and practically applicable proposals for preventive measures, key inputs were the empirical findings, results, and knowledge obtained through research projects conducted by the authors’ team as well as by other organisations.

Within the activities of the Centre for Environmental Research: Waste and Circular Economy and Environmental Safety (CEVOOH; SS02030008), the TGM WRI team has long addressed the issue of food waste in Section 1.C on Biodegradable Waste. In previous years, the aim has been to develop a national methodology to meet reporting obligations for food waste generation in the Czech Republic at the national level for the European Union authorities [9]. The methodology covers all stages of the food supply chain (primary production, processing and manufacturing, retail and other food distribution channels, restaurants and catering services, households) and is based on a calculation approach strictly aligned with EU requirements and the waste catalogue. The methodology has become the main stimulus for an interdisciplinary, independent approach to precise reporting and documentation of waste generation in the primary production and food processing segments.

The main indicator for the municipal sector is the generation of household food waste, determined based on data from the Waste Management Information System (ISOH). The calculation includes waste from selected catalogue items (20 01 08, 20 01 25, 20 02 01, 20 03 01) with handling codes A00, AN60, and BN30. The resulting value represents the annual quantity of food waste generated by households participating in the municipal system. The purpose of monitoring this indicator is to assess whether food waste generation is decreasing. Trend analysis enables municipalities to evaluate the effectiveness of measures related to collection optimisation, food redistribution, and public awareness campaigns.

The supplementary indicator I.KO expresses the quantity of avoidable food waste, i.e., waste that could have been consumed but was discarded. It uses data from ISOH and conversion factors established for individual components of municipal waste – mixed municipal solid waste (MSW), biodegradable waste, and market waste. The combination of both indicators provides municipalities with a comprehensive tool for planning, evaluating the effectiveness of measures, and monitoring progress in food waste prevention.

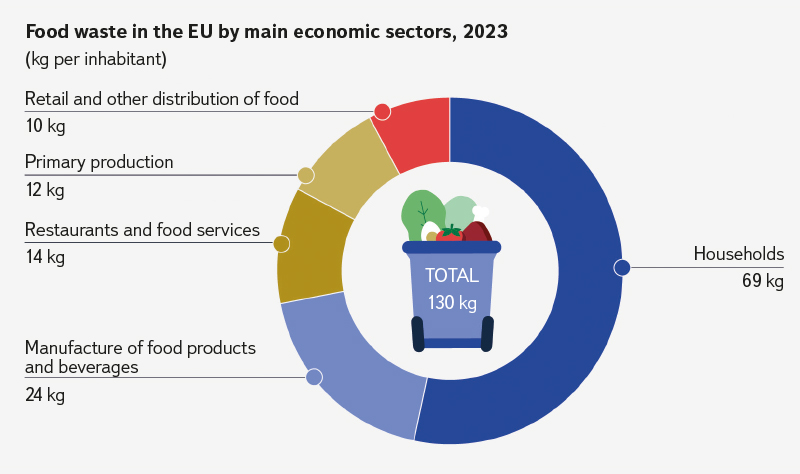

For a detailed understanding of the quantity and composition of the biodegradable fraction of mixed municipal waste, and for the subsequent development of realistic proposals for measures, insights from MSW analyses are essential. These analyses were carried out in several projects: first, within the research project Waste and Prevention of Its Generation – Practical Procedures and Activities for Implementing the Obligations of the Regional Waste Management Plan of the Capital City of Prague (Growth Pole programme; CZ.07.1.02/0.0/0.0/16_040/0000379, Fig. 2), and currently within the ongoing project Effective and Sustainable Management of Food Waste in Municipalities (acronym NAPO, Environment for Life 2 programme, TA CR, No. SS07010095, 2024–2026). The main aim of the second project is to establish a previously unrealised systematic approach and to develop a comprehensive tool for the sustainable management of food waste for municipal authorities and their associations in the Czech Republic. Dozens of MSW analyses, with a particular focus on food waste, have provided detailed information on the composition of these wastes and have identified the fractions with the greatest potential for waste prevention. Equally important is the highly active involvement of representatives from selected cooperating cities and municipalities, with whom proposals for preventive measures were consulted in connection with the ongoing results of MSW analyses and the operational experience of officials responsible for waste management. The preliminary results of these MSW analyses clearly confirm that there is a sufficient quantity of food waste in municipal waste with potential for utilisation and waste prevention (Fig. 3); the complete results of the MSW analyses will be published in 2026.

Fig. 2. One of the key activities in identifying food waste and obtaining the necessary data is the analysis of MSW in municipalities (photo: authors’ archive)

Fig. 3. After being sorted from the MSW, food waste is photo-documented and provided with a description of its condition, expired warranty period, etc. (photo: authors’ archive)

In research and awareness-raising, the initiative Save Food (Zachraň jídlo) plays an important role, highlighting the extent of food waste through campaigns and collaboration with retailers, schools, and producers, while providing concrete recommendations on how to prevent it [10]. In 2022, an extensive study by the Food Bank Prague and Mendel University in Brno quantified the scale of food surpluses in retail and proposed improvements to the food donation system [11]. In collaboration with the Faculty of Education at Charles University and the Faculty of Business and Economics at MENDELU, the project Smart with Food (Chytře s jídlem) was launched, focusing on food waste and aiming to raise awareness and change the behaviour of children, schools, and households [12]. Household shopping and cooking practices are further supported by the platform Buy What You Eat (Kup, co sníš), which offers advice, tips, guides, recipes, and inspiration on how to use ingredients as efficiently as possible, minimising unnecessary losses [13].

Experience has also been gained through the project and platform I Sort Gastro (Třídím gastro), which provides comprehensive services by the company Energy Financial Group (EFG) focused on the separation, collection, and energy recovery of biodegradable kitchen (catering) waste [14, 15]. In the management of already generated food waste, the results of research activities related to composting and biogas plants were also utilised [16–18].

Other relevant sources that supported the development of preventive measures include expert materials from the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic, ISOH statistics, EKO-KOM outputs (MSW analyses), and reports from municipalities that conducted their own MSW analyses. These materials enable comparisons across different regions, municipality sizes, and types of municipalities, help identify key determinants of food waste, and allow the design of measures that are practically implementable under the conditions of various municipalities [19–21].

RESULTS

Systemic measures at the national or municipal level targeting food waste must lead to a reduction in the production of mixed municipal waste. This reduction can be achieved through two mutually complementary approaches:

- through consistent and well-planned waste prevention (including not only food waste itself but also the wastes that are sometimes inevitably generated during food production, such as plastic packaging in which food is discarded),

- through a significant increase in the efficiency of separation and subsequent utilisation of food waste that has already arisen within cities and municipalities.

Proposed measures can be applied individually within a municipality. However, it is more effective to integrate these solutions into a coherent system and exploit potential synergies (for example, combining awareness-raising with technical interventions, or infrastructure with incentive tools). The goal is to design the most comprehensive solutions possible, enabling the development of efficient, adaptable models that can function in diverse local conditions.

When implementing the proposed measures in practice, it is necessary to comply with current legislation and also take into account regulations concerning other specific areas (particularly public health protection, hygiene standards, and technical norms). Technical solutions (such as bin sizes, collection logistics, and composting or biogas capacities) should be dimensioned appropriately to local conditions.

From the perspective of the municipal waste producer (i.e., the municipality) prevention is absolutely key, as it significantly reduces waste management costs (for both residual and separated waste). However, waste prevention measures cannot be strictly enforced, or only to a very limited extent – for example, through differentiated waste fees, incentives for households producing low amounts of waste, or participation in awareness programmes. Voluntary motivation therefore plays a crucial role in preventing waste generation, and this can be strongly influenced by properly targeted awareness-raising. The second dimension involves creating an environment that enables motivated citizens to live a “zero-waste” lifestyle, supporting urban composting, establishing platforms for food redistribution, and similar initiatives.

Proposals of preventive measures

Biodegradable municipal waste and support for composting

Biodegradable municipal waste (BMW), a substantial part of which consists of discarded food, accounts for approximately 40 % of municipal waste. At the same time, it is the only type of waste that citizens can fully and legally utilise in the home environment, even in large quantities (Fig. 4). Landfilling of biowaste is also restricted by legislation, and waste producers are obliged to implement measures leading to separate collection and further utilisation of BMW.

Fig. 4. Today, we can see composters not only in family houses, but they are also increasingly used by residents of panel houses in housing estates (photo: authors’ archive)

There are several methods for ensuring the utilisation of biodegradable waste, but they differ considerably in terms of efficiency, financial costs, and environmental burden. Given the complexity of the issue, all methods have a place within waste management. However, it is advisable that their implementation and support follow a hierarchy similar to that applied to waste management in general: measures with the lowest environmental (and often financial) costs should be prioritised, with other solutions considered only once the more favourable options have been exhausted.

Domestic and garden composting

According to the experience of municipalities, grant support for the purchase of garden composters for residents with gardens, users of inner courtyards, and similar settings has proven effective. Grant schemes can also be targeted at the acquisition of indoor vermicomposters intended for domestic composting of kitchen waste. A starter culture of earthworms must be placed in the vermicomposter, preferably a selectively bred, highly efficient species of so-called Californian earthworms (Eisenia andrei), which prefer higher temperatures, reproduce rapidly, and process kitchen waste very effectively. However, they require care comparable to that of a specific “domestic animal”, namely the provision of sufficient food (biowaste), appropriate temperature, and adequate moisture. Users of vermicomposters therefore need to be familiar with the requirements of the earthworms and the rules of their care to ensure that the composter functions properly and that the earthworms do not die.

Community composting

Community composting refers to the shared composting of organic waste by multiple households, typically neighbours (residents of a single apartment building or entrance, or users of suitable shared spaces). Composting may take place in closed or open composters, or on compost heaps (Fig. 5). A composter located in a publicly accessible area must be enclosed and lockable, with keys held only by authorised users. The composter should be sited so that it does not cause nuisance through potential odour or insects and is reasonably accessible to all users. It is essential that at least one administrator is designated within the user group; this person oversees cleanliness, ensures proper compost management, and organises the use of the produced compost (or delegates necessary tasks to other users). Each group should establish internal operating rules (definition of acceptable compostable waste, user responsibilities, responsibility for equipment, etc.). Composters should preferably be insulated (to allow year-round use), lockable, and multi-chambered, with one chamber used for collecting fresh waste and the others for compost maturation.

Fig. 5. The disadvantage of community composting is the lower possibility of checking the deposited waste from a larger number of citizens, when waste in plastic bags or even waste that is not related to composting at all may appear at the collection point (photo: authors’ archive)

Composting and the treatment of biowaste in schools

Schools and other institutions may compost biowaste provided that several rules are observed. Composting should involve plant residues only, not food leftovers. The composting process must not pose a risk to the environment or to human health; it therefore has to be carried out properly, with no leakage of leachate into watercourses or similar pathways. The resulting compost is ideally used on school grounds.

To ensure high-quality composting, biowaste must be consistently sorted at the point of generation; that is, during food preparation and in classrooms. Collection should take place in special ventilated bins placed in each classroom (or at each waste collection point within the school). Ventilated bins, into which compostable bags are inserted, ensure that the waste dries out rather than rotting. The bins must be closable to prevent pests, particularly fruit flies, from accessing the biowaste. The removal of bags containing biowaste should take place at least once or twice a week, or more frequently if necessary. The compost must be turned (aerated) at least twice a year, and it is necessary to ensure the mixing of residues with a high nitrogen content (fruit, food preparation residues) with carbon-rich materials (grass, wood chips). The resulting stabilised compost (after approximately one year) can be used for the maintenance of school grounds. It is also advisable to involve pupils and students in the system (education, taking responsibility), for example by having them remove biowaste, check the quality of sorting, and care for the compost. The transformation of organic residues into compost and fertiliser is also an interesting topic for biology lessons.

Community fridge

Public spaces where unwanted but still usable items can be left and freely taken by others have two positive effects. They facilitate the act of “not throwing away things that I no longer need” and enable their donation beyond one’s own family or friends. They also make it possible to donate items that can otherwise be given away (or accepted) only to a limited extent, in particular due to social conventions or feelings of embarrassment (unsuitable gifts, food, etc.). At the same time, items are not devalued (neither physically nor “emotionally”), for example by being left next to waste containers in the hope that someone might take them. Experience from the operation of similar “sharing points” (community fridges, clothing exchanges, libraries) shows that they are used both by people in genuine need (especially for clothing and food) and by people motivated by environmental concerns (consumption of “almost discarded” food), as well as simply by people willing to try something different and sufficiently open-minded, particularly students (for example with food and books).

In practice, community fridges are the most common form of such sharing points; however, in principle, any products can be shared in this way, provided that it is technically feasible, that sufficient supply and demand exist, and that people are willing to offer items free of charge and to take them from an “unverified source”.

A community fridge requires a permanent electricity supply, daily monitoring (proper functioning of the refrigerator, inspection of contents, and removal of unsuitable or spoiled food), and placement in a location protected from weather conditions and direct sunlight. For these reasons, their maintenance is most often undertaken by operators of cafés or other facilities; some are located in university dormitory premises, while others are installed at municipal offices. In the case of a community fridge, it is essential to ensure strict operational management and to provide clear, prominent notices setting out the operating rules and informing users that consumption of stored food is at their own risk. These operating rules, which define what may be placed in the fridge and under what conditions, must be carefully formulated and publicly displayed. The safest items are purchased foods with an unexpired best-before date that remain unopened, as well as undamaged fruit and vegetables. In some community fridges, it is also possible to leave home-prepared food, as well as opened packages where this does not affect quality (eggs, pasta, shelf-stable foods), or shelf-stable foods with an expired best-before date for which any decline in quality is minimal (pasta, legumes). It is also advisable to designate an uncooled space for storing foods that do not tolerate cold and, in particular, humidity (such as potatoes), or that do not require refrigeration at all (shelf-stable foods).

Discounted food apps

The prevention of food waste has shifted markedly towards digital solutions in recent years, among which mobile applications connecting businesses with end consumers play a key role. In the Czech Republic, the most widely used platforms are Nesnězeno (Uneaten) and Too Good To Go, which enable customers to purchase unsold meals or food at a reduced price [22, 23]. This approach not only saves money for households but also helps to reduce the amount of food discarded and supports local food service businesses. While Nesnězeno, owing to its longer presence on the market, has built a strong network with more than 1,700 partner establishments, the newer Too Good To Go relies on international experience and technological innovations, including a tool using artificial intelligence for stock planning. Both apps primarily target urban and younger populations and employ the element of surprise, as customers often do not select a specific meal in advance but instead purchase a so-called rescue package. In the context of rising food prices, increasing pressure for sustainability, and the high share of households in overall food waste generation, these applications represent an important instrument for the systemic reduction of food losses.

Using tap drinking water instead of bottled water

Water as a food item is often overlooked. The public water supply provides high-quality water that is regularly monitored by the supplier for hygienic standards, is ideally stored (in cool, dark conditions), and, with continuous turnover, remains fresh. Compared with bottled water, it is very inexpensive; one litre of drinking water (water supply and sewerage charges) costs only a few halers, whereas a litre of bottled water costs several Czech crowns. Bottled water is also a source of large amounts of plastic waste, a substantial proportion of which is transported abroad for further processing. It is therefore necessary to focus on prevention rather than solely on recycling, which in itself represents a significant environmental burden (production, transport, and the recycling process itself).

In the Czech Republic, high-quality drinking water is taken for granted. Nevertheless, bottled water retailers have been so successful with their marketing campaigns that tap water is often perceived as inferior. This perception needs to be challenged through targeted activities and the promotion of tap water.

One simple yet effective preventive measure to reduce waste from single-use packaging is the provision of tap water to customers in restaurants and cafés. Promoting the consumption of tap water helps to limit the use of bottled beverages and thus also reduces the amount of plastic and glass packaging that ends up as waste. Municipalities can support this measure through awareness campaigns, labelling establishments that offer tap water, or providing technical support (for example, filtration systems).

Food banks

Food banks in the Czech Republic are key actors in the fight against hunger and food waste [24]. They represent an important component of the system providing assistance to people in need, while simultaneously actively combating food waste. Their primary mission is to collect safe food that would otherwise end up as waste and to distribute it to those who need it most. This system operates thanks to close cooperation with retail chains, food producers, farmers, volunteers, and an extensive network of recipient non-governmental organisations.

Food banks obtain food from a variety of sources. These include primarily surplus food from retailers (e.g. products approaching their minimum durability date or with damaged packaging), unsold products from manufacturers and growers, as well as donations from the public collected through food drives, such as the nationally well-known Food Collection.

The collected food is subsequently sorted, stored and distributed through partner charitable and humanitarian organisations. These organisations then ensure that the assistance reaches the target groups directly. The most common beneficiaries include families in crisis and single parents, seniors on low incomes, people experiencing homelessness, individuals with disabilities or chronic illnesses, and similar groups.

Improving the efficiency of sorting biodegradable waste

Municipalities in the Czech Republic have been obliged to enable the separate collection of biodegradable waste since 2015, initially only on a seasonal basis. Since 2019, municipalities have been required to ensure facilities for the separate collection of biowaste throughout the entire year. At least at a general level, such a system is therefore in place in the Czech Republic. However, MSW analyses carried out by the authors’ team and other bodies indicate that the efficiency of these systems and their more substantial impact on reducing the amount of BMW in MSW disposed of in landfills have so far remained relatively low (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The ongoing results of the MSW analyses carried out as part of the NAPO research project show that the share of usable BMW is still around 40 %

Separate collection and the introduction of catering (food) waste collection for municipal residents and businesses

Here, catering waste refers to waste classified under catalogue code 20 01 08 – Biodegradable waste from kitchens and canteens. Leftovers of cooked meals and similar waste from catering facilities and households are usually not collected separately and largely end up in mixed municipal waste. Catering waste can only be composted to a limited extent due to the risk of rodents, insects and potential infection (especially meat and cooked food residues). As the level of separate collection of other waste fractions improves, the share of catering waste in mixed municipal waste increases. This is a waste fraction that can be further utilised (e.g. in biogas plants); however, is difficult to use directly for energy recovery (by incineration), and its disposal (as biodegradable municipal waste) in landfills is increasingly restricted by legislation. These factors all underline the need to divert this waste stream and to introduce consistent separate collection and recovery. As with other waste fractions, separation at the source is essential, because subsequent sorting is practically impossible and mixing significantly reduces the potential for further utilisation. A model example of good practice is the already mentioned Třídím gastro initiative [14].

Collection of edible oils at the point of use (canteens, restaurants)

Used edible oil from households and catering establishments still ends up in significant quantities in the sewer system or in mixed municipal waste. Such practices can cause pipe blockages, damage to sewerage infrastructure and increased maintenance costs.

Edible oils and fats, however, represent a recoverable raw material that is collected and sorted under catalogue code 20 01 25 – Edible oil and fat. A number of companies are involved in the collection and reuse of this oil; the technology is well established and there is demand for the material, which is even purchased (typically for a few Czech crowns per litre). Selected locations can also serve as collection points for oil from households (most commonly schools or school canteens). The level of separate collection of this material (i.e. the proportion of oils ending up in the sewer system) is closely linked to public awareness of the potential damage caused by oil in pipes (blockages, the need for repairs).

Information and awareness campaigns

In the area of preventing the generation of BMW and food waste, the public is a crucial target group, capable of effectively influencing the quantity and type of waste produced in everyday life. An effective information campaign can therefore quickly create (and thus have an immediate impact) and, throughout the implementation of preventive measures, ensure the continuous operation of an openly accessible information base on waste prevention at various levels. It thus acts both immediately (short-term) and over the long term. The strategy for disseminating information in this area is considered one of the most important forms of intervention.

Awareness-raising is absolutely crucial to support the public in activities aimed at reducing waste generation. This is because such solutions are often less convenient for users (for example, the need to bring your own containers, cups, etc.), whereas waste seemingly “disappears” once discarded. It is therefore necessary to strengthen understanding of the connections involved (the link between a discarded cup and a landfill or incinerator, which are perceived negatively) while simultaneously promoting and disseminating proper, practical approaches for living with minimal waste. This applies across many levels – from individual citizens to small businesses, large companies, and public administration or institutions. Simultaneously, it should be noted that the actual effectiveness of information campaigns can vary widely. As confirmed by analyses of MSW in municipalities with intensive public awareness initiatives – encouraging residents to collect and separate BMW and food (catering) waste, including the provision of a sufficient number of street collection containers and bins for households – municipalities often struggle to achieve significant reductions in waste generation. This is largely due to residents’ non-compliance and failure to follow the rules, meaning that even substantial financial investments do not always result in meaningful decreases in the amounts of these wastes (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Citizen indiscipline and failure to respect basic rules for MSW collection and sorting remain evident in some municipalities, even after years of information and awareness campaigns (photo: authors’ archive)

Information and awareness campaigns can encompass a wide range of activities targeting residents, while also linking them to community events, schools, or local businesses. Municipalities can use various channels to disseminate and promote these campaigns, such as the municipality’s website, leaflets, local newspapers, labels on collection containers, mobile applications, official social media pages, and similar platforms. The range of possibilities is quite extensive and may focus on activities such as:

- regularly inform the public about current developments in the field of the circular economy and waste management within the municipality;

- inform about the types of waste collection containers, their colour coding, the placement of labels and internationally recognisable pictograms indicating accepted and non-accepted waste on the containers, and the use of QR codes enabling the reporting of issues related to collection points;

- organise guided visits to facilities that form part of the waste management system (landfills, sorting lines, recycling centres, composting plants, biogas plants, energy recovery facilities, manufacturers using returnable packaging, etc.); the purpose of these visits is to demonstrate real-life operations and to dispel myths and misconceptions about waste management, such as the claim that “separating waste makes no sense because it is all later dumped into a single refuse truck or landfill pit anyway”;

- participate in science and research projects and inform the public about these activities;

- disseminate information on initiatives, events, and organisations whose activities aim to reduce food waste (such as Neplýtvej potravinami, Zachraň jídlo, Kup, co sníš, food banks, and similar initiatives)

- organise, or co-organise, courses promoting properly planned food purchasing and cooking from primary ingredients (unpackaged foods);

- disseminate information about social and communication platforms and applications for electronic devices;

- promote zero-waste shopping and related initiatives, provide information on local retailers, and explain the hygiene requirements that must be met (appropriate containers and subsequent storage of products at home to prevent deterioration);

- provide information on available financial support (grant programmes) aimed at supporting production and sales practices that minimise the generation of food waste (sales into customer-owned containers, use of returnable packaging in production and retail);

- disseminate information on examples of good practice;

- provide advisory support in legislative, accounting, and hygiene matters (in cooperation with public health authorities and retail operators) related to the sorting and management of food waste and the use of returnable/customer-owned packaging; consider issuing the manual in other languages as well (at least as a translation of the electronic version);

- provide financial incentives for, and differentiate between, citizens and entities that take a responsible approach to the sorting of food waste;

- create interactive maps indicating collection containers suitable for depositing food waste, community fridges, and zero-waste shops (including, for example, outlets offering coffee into customers’ own containers), incorporating data filtering options, information on opening hours, contact details, and similar features;

- provide long-term support for municipal projects and recommend them to residents (home composters, community composting, pilot projects for collection and sorting, etc.);

- through schools, educational institutions, and leisure-time centres, organise public competitions (currently popular among pupils and students, for example photo competitions) focused on identifying and rewarding original ideas and solutions in the field of food waste prevention, proper food waste management, and the use of recycled materials (for example composts).

Revenues and expenditures in municipal waste management

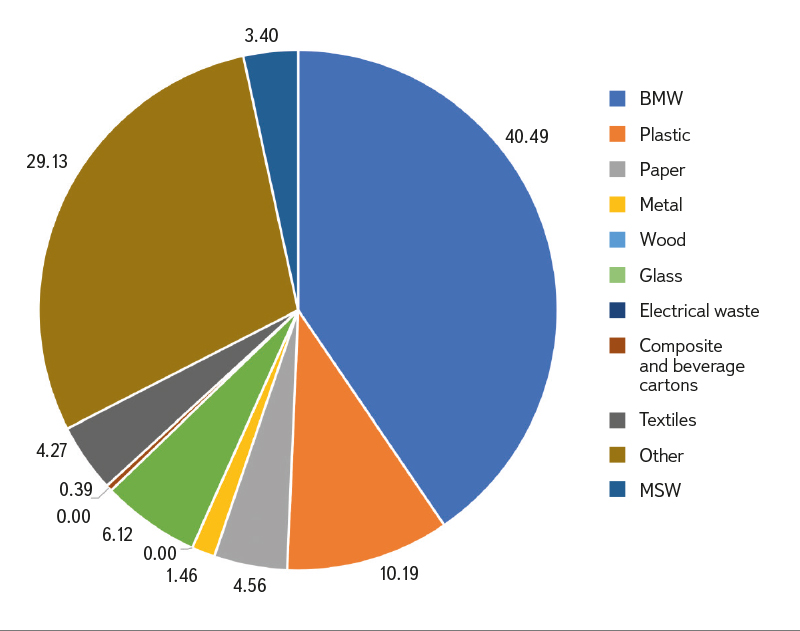

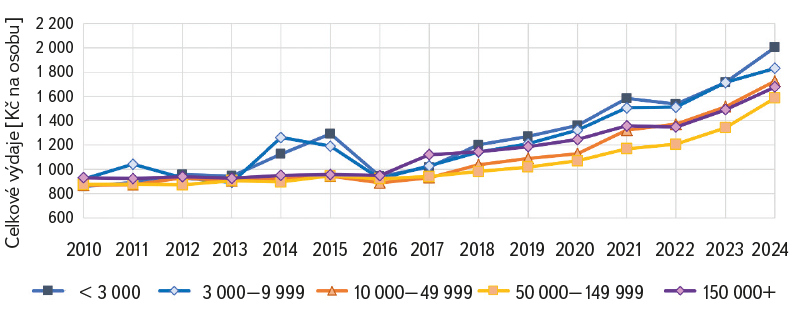

Within municipal budgets, waste management is tracked through revenues, expenditures, and the financial relationships between them. These are further specified using budget items, paragraphs, and similar classifications, monitored according to the budgetary structure defined by Decree No. 412/2021. Capturing financial relationships in the budget is closely linked to the municipalities’ waste management models. These financial relationships reflect different approaches, ranging from municipalities independently performing waste management activities through their offices, to purchasing services from collection companies, establishing municipal organisations, or cooperating within associations of municipalities. The choice of model depends primarily on the size of the municipality, its organisational capacity, and economic stability. Over the long term, a significant increase in the burden of waste management on municipal budgets can be observed. While in 2010 it amounted to CZK 2 billion, by 2024 it had risen to CZK 7 billion, representing an increase of 241 %. The overall net financial impacts of waste management in municipalities are mainly driven by the growth in municipal expenditures on waste management. From 2010 to 2024, total municipal spending on waste management increased from CZK 9.3 billion to CZK 19.7 billion. This 111 % increase was influenced by inflation; however, even after adjusting for inflation, there remains a real increase of 29 % (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Development of municipal waste management in 2010–2024 (Ministry of Finance, State Treasury Monitor)

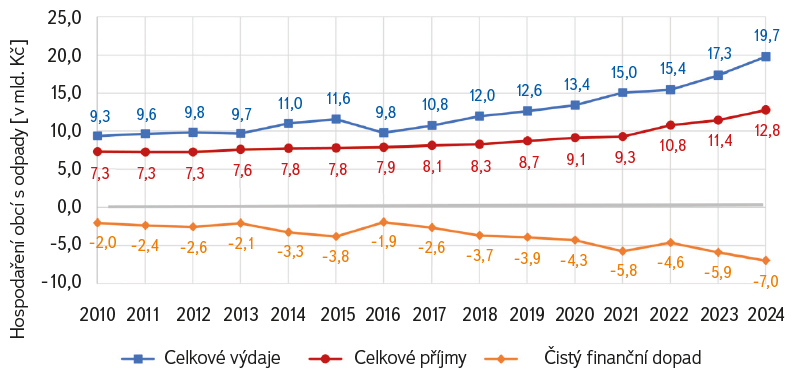

Municipal expenditures on waste management mainly relate to costs for collection and transport, waste utilisation and disposal, prevention of waste generation, and monitoring (Fig. 9). Municipalities pay these costs to waste collection companies, and they also include fees for landfill disposal. Most of these expenses are operational, while capital expenditures cover items such as equipping collection yards, composting facilities, or acquiring collection vehicles. Expenditure levels vary according to the size of the municipality; in 2014–2015, smaller municipalities had higher capital expenses due to EU subsidies. Over the long term, the highest per capita costs are borne by the smallest municipalities, and differences between size categories are widening. Higher unit costs in small municipalities may be linked to lower collection efficiency, underutilisation of capacities, and limited opportunities for optimisation. This highlights the need for system rationalisation, increased prevention, and stronger support for waste separation.

Fig. 9. Total municipal expenditures on waste management by size category in 2010–2024 (Ministry of Finance, Treasury Monitor / Czech Statistical Office)

The main source of municipal revenue in waste management is the local fee for the municipal waste management system and the fee for municipal waste disposal, set by a generally binding municipal ordinance. Some municipalities may also collect these fees through contractual arrangements. Other sources of revenue include payments for sorted waste, contributions from collective systems, and income from landfill disposal fees collected by the municipality where the facility is located. Additionally, some municipalities may charge fees for waste that they transport in bulk to landfills (e.g., construction debris), with the fee based on the costs of disposal.

Over the long term, it has been observed that per capita revenues are highest in the smallest municipalities and decrease as municipal size increases, with the exception of the very largest municipalities (Fig. 10). Between 2021 and 2024, revenues across all municipal size categories increased on average by about one third. This increase is primarily driven by the size of the local waste fee, which constitutes a major component of total municipal revenues.

Fig. 10. Total municipal revenues from waste management by size categories (Ministry of Finance, Treasury Monitor / Czech Statistical Office)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The transfer of responsibilities in the field of the circular economy and waste management to municipalities has been increasing in recent years. Municipalities are required not only to ensure the implementation of systemic measures and to achieve statutory targets, but also to cope with a shortage of qualified staff, limited access to relevant information, and growing pressure on municipal budgets. An analysis of the current situation indicates that, without long-term and systematic support for municipal activities in these areas, the Czech Republic may face significant difficulties in the future, both in achieving the expected transition to a circular economy and in ensuring the long-term sustainability of the waste management system, as well as in meeting (often very ambitious) environmental targets.

Measures to prevent food waste and reduce the generation of biowaste are not merely a cost; they represent an investment in a sustainable future – resource conservation, emission reductions, support for the local circular economy, and an improved quality of life. A municipality that becomes actively involved can achieve not only environmental benefits, but also financial savings, greater self-sufficiency, and strengthened civic responsibility.

In response to the growing financial burden, municipalities are seeking new motivational and systemic approaches. Some are introducing volume-based charging systems that encourage residents to reduce the generation of mixed municipal waste, while others make use of grant programmes (for example Operational Programme Environment and National Recovery Plan) to invest in waste collection centres, composting facilities, and biowaste infrastructure. An important trend is the development of inter-municipal cooperation, which makes it possible to share costs, optimise collection systems, increase the effectiveness of implemented measures, and achieve economies of scale.

Rising costs of operating waste management systems confirm that waste prevention, including food waste prevention, represents the most economically and environmentally effective strategy.

Long-term support for waste separation, reduction of mixed municipal waste volumes, public education, and, in particular, a strong emphasis on waste prevention can significantly contribute to increasing municipal revenues from waste management while simultaneously reducing the overall burden on municipal budgets. More efficient waste management thus represents not only an environmental but also an economic benefit for municipalities of all sizes.

From the perspective of food waste issues, the following concise conclusions can be defined on the basis of experience and available information to date:

- At present, there are two types of end facilities for the treatment of food waste in the Czech Republic: biogas plants and composting facilities. As stated in the analytical section of the Waste Management Plan of the Czech Republic for 2025–2035, with regard to the planned national targets, current capacities are insufficient. Investments in infrastructure will therefore be unavoidable in the coming years.

- Analyses of MSW carried out by the author team show that the proportion of BMW, which includes food waste, still accounts for around 40 % by weight, despite the fact that the separate collection of BMW at the municipal level has been in place since 2019.

- The analyses also show that even municipalities with relatively substantial information campaigns and financial incentives aimed at increasing the separate collection of BMW and catering waste have, in many cases, not yet achieved a significant reduction of these waste streams in MSW.

- For the prevention of food waste at the municipal level, continuous influence on citizens’ behaviour is essential. However, despite considerable effort on the part of municipalities, effectiveness may remain low. In the future, increased pressure can be expected for greater financial incentives for responsible citizens who are actively engaged in the system.

- To improve the current situation, long-term and systematic support for municipalities by the state is absolutely essential. The most important aspects include providing information on examples of good practice, creating sharing mechanisms, standardising procedures, integrating the topic into the education system, publishing data and case studies, supporting effective systemic solutions, providing grant support, and ensuring mutual communication when planning new legislation and setting national targets in relation to municipalities.

- For Czech municipalities, it is advisable to start with measures that require low capital investment but deliver a high local impact. It is necessary to assess the local situation (MSW analyses, citizen participation) and to select appropriate technologies and approaches (home or community composters, collection systems, mobile applications). Available grant programmes and funding schemes should be actively utilised, and networks of cooperation should be established (for example between municipalities, associations, non-profit organisations, food banks, and farmers) to share experience and optimise costs.

- Among preventive measures, composting activities (home, community, and school-based) and food redistribution have proven to be relatively effective.

- Municipal budgets are coming under increasing pressure due to the growing demands of waste management and the circular economy. For small municipalities, one possible solution appears to be their grouping into larger units with greater bargaining power vis-à-vis collection companies and entities involved in the treatment of waste, including (but not limited to) food waste.

- The development of waste prevention systems and efficient management of biowaste delivers synergistic benefits: it reduces the carbon footprint, improves soil quality through the return of organic matter, supports the local economy, and contributes to meeting the objectives of European strategies such as Fit for 55, the European Green Deal, and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal No. 12 (Sustainable Development Goal 12 – Responsible Consumption and Production). Sustainable and self-sufficient waste management thus becomes not only an environmental, but also a strategic pillar of development for Czech municipalities.

Acknowledgement

The paper was produced within the framework of long-term research activities of TGM WRI focused on the prevention and management of food waste, financially supported from institutional funding provided by the Ministry of the Environment of the Czech Republic under the Long-term Concept for the Development of the Research Organisation.

The Czech version of this article was peer-reviewed, the English version was translated from the Czech original by Environmental Translation Ltd.