ABSTRACT

In the last quarter of the 18th century, a unique system for timber floating was built in the region of Nové Hrady. Its creation is linked to the name of the then owner of the Nové Hrady Estate, Johann Nepomuk Buquoy, while the project and its implementation were designed and overseen by engineer Johann Franz Riemer. The uniqueness of the system lay in the fact that it allowed the floating of both loose timber (logs) and bound timber (rafts), even on the narrow and low-capacity streams of the Novohradské hory (Gratzen Mountains). The basis of the navigation system was formed by modified (navigable) watercourses, on which there were reservoirs (ponds) ensuring the necessary amount of water for floating timber. The beginnings of the construction of the navigation system date back to the second half of the 1770s. Materials preserved in the archival records of the Nové Hrady Estate provide insight into the beginnings of the waterway construction in 1780–1784. In 1783, the first part of the construction of the navigation system was completed. From that year on, logs were transported to České Budějovice and the first rafts to Prague. In the section to České Budějovice, the waterway included the Pohořský stream, which connects to the Černá and Malše rivers. After 1783, the expansion of the navigation system continued to the upper reaches of the Černá river and its tributaries. The navigation system was completed at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries by making smaller tributaries of the Černá river navigable and with the construction of reservoirs on those streams. The navigation system was maintained and operated until the first half of the 1940s.

INTRODUCTION

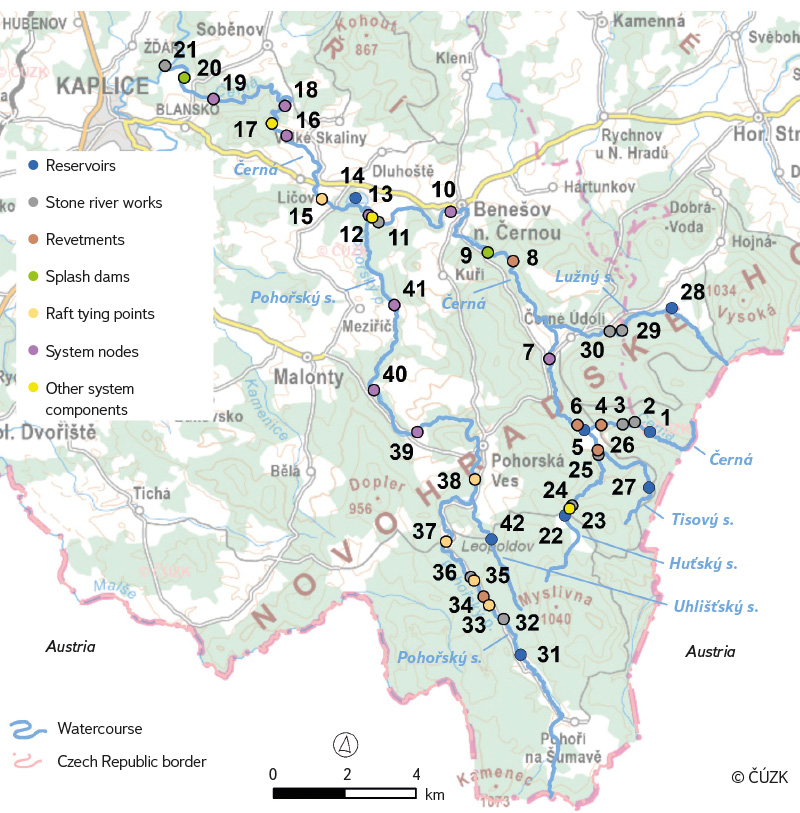

From the late 1770s to the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, a unique navigation system was constructed in the Novohradské hory (Gratzen Mountains) and their foothills, enabling the transport of both loose timber and bound timber. The key part of the system was located on the Nové Hrady Estate, which had been owned since 1621 by the Buquoy family, of French origin [1]. To transport the abundant timber from the forest districts of the Gratzen Mountains, the Černá river and its tributaries were used. From Kaplice, the logs were driven further to České Budějovice along the Malše river (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map of key parts of the navigation system

Based on a set of surviving and hitherto systematically unprocessed sources from the Nové Hrady Estate archive, this study attempts to map in greater detail the construction and operation of the navigation system in the last quarter of the 18th century, with a primary focus on the years 1780–1784. The study concentrates on the more general aspects of the system’s construction and development and builds on insights presented in the existing professional literature, which has mainly addressed the system during its peak and later periods of operation.

Purpose of the navigation system and the context of its creation

As a result of the so-called “wood crisis” – caused by the massive exploitation of forests in response to growing demand for wood as fuel, industrial, and construction material – around the mid-18th century, the demand for firewood and construction timber increased sharply, especially in large towns. This created an opportunity for owners of large forest estates to monetise previously almost untouched timber resources. The waterway represented the cheapest and, at the time, practically the only means of transporting timber. From a technical perspective, there were two methods of floating timber along waterways. The first was the log driving (Holztrift, Holzschwemme). This method was used to transport firewood (Brennholz) and later also pulping timber (Schleifholz) intended for cellulose production. The second method was timber rafting (Holzfloßung),

used for floating long logs. Individual logs were joined into rafts (Flöße), which were then bound together into large rafts called ‘pramms’ (Prahm) many tens of metres long. This method was used to transport construction timber. These large rafts could also carry additional cargo, such as logs, various wooden products (shingles, wooden rods, planks), or other goods – for South Bohemian rivers, this included salt from the Alpine regions. This practice increased the profitability of timber rafting. Historical records indicate that as early as the first half of the 1780s, efforts were made to increase the profitability of the Buquoy navigation system. Later on, this was apparently common practice: at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, rafts carried firewood, timber for mines (Grubenholz), and railway sleepers (Schwellen) [2–4].

The beginnings of efforts to transport timber from the forests of the Gratzen Mountains date back to the mid-18th century. In 1748, František Karel Berner proposed log driving using reservoirs. The first attempt to float timber from the Gratzen Mountains forests was made by entrepreneurs Goldberg and de Sommer in the mid-18th century [5, 6]. They drove logs intended for the manufacture of masts to Hamburg, but the endeavour remained only an experiment; systematic timber floating required the river channels to be made navigable and modified. At the time, the then-owner of the Nové Hrady Estate,

Count Franz Leopold Buquoy (1703–1767), was presented with several proposals for large-scale log driving from the Gratzen Mountains. These proposals differed considerably, particularly regarding the financial costs of establishing the system. They also included a proposal by the engineer Johann Franz Riemer from 1761, which involved the construction of reservoirs and the improvement navigation of river channels. Due to unfavourable circumstances – for instance, the famine of 1770–1772 – Riemer’s proposal was only implemented in the second half of the 1770s under Count Johann Nepomuk Buquoy (1741–1803) [7].

Geographical delimitation of the navigation system

The core of the system consisted of navigable streams. The principal waterways were the Malše (Maltsch), the Černá (Schwarzaubach) and Pohořský stream (Buchersbach). Gradually incorporated into the system were the Uhlišťský stream (Kohlstätterbach), a tributary of the Pohořský stream, and the tributaries of the Černá – Lužný (Luggaubach), Huťský (Gereutherbach) and Tisový stream (Eibenbach).

A key element of the navigation system was the ponds or reservoirs constructed on each of the navigable streams. Since the streams generally did not provide sufficient water to transport timber, the navigation systems could not function without this component. In sources from the 1780s and 1790s, the ponds are referred to as Reservoire, that is, reservoirs. Some of them originally served as fishponds, but most were created specifically as part of the navigation system. By the end of the 19th and first half of 20th centuries, the reservoirs were referred to exclusively as ponds (Triftteiche). The navigation system also always included one additional pond located off the waterways, below the confluence of the Černá river and Pohořský stream. This pond supplied water for log driving along the lower reaches of the Černá and the Malše. The composition of the ponds was changing over the course of the system’s development.

In the first half of the 20th century – during the peak and late phases of the navigation system – the following ponds were in operation: Pohořský (Buchersteich) and Uhlišťský (Kohlstätterteich) on their eponymous streams, Zlatá Ktiš (Goldener Tisch) on the Černá, Mlýnský (Mühlbergteich) on the Lužný stream, and Huťský (Gereutherteich) and Tisový (Eibenteich) on their eponymous streams (Fig. 2). Just below the confluence of the Černá and Pohořský stream, the Buquoy family leased the Kancléřský pond (Kanzlerteich) from

the Český Krumlov prelature [3].

Fig. 2. Uhlišťský Pond – one of the navigable reservoirs (photo: M. Bureš, July 2024)

Fig. 2. Uhlišťský Pond – one of the navigable reservoirs (photo: M. Bureš, July 2024)

By releasing water from the ponds (reservoirs), a surge of water was created that enabled the transport of loose or bound timber along the route from the Gratzen Mountains to České Budějovice. Water was discharged through wooden pipes placed at the lowest point of the dam (Fig. 3). The amount of water released was regulated by equipping each pond with multiple pipes (two to four, varying by pond) and by the ability to open each pipe only halfway.

Fig. 3. Remains of a wooden outlet pipe at Huťský Pond (photo: M. Bureš, July 2024)

Fig. 3. Remains of a wooden outlet pipe at Huťský Pond (photo: M. Bureš, July 2024)

Watercourses had to be modified for transport purposes. Making them navigable involved a wide range of measures aimed at creating a smoothly passable waterway. The channels had to be cleared of rocks and sand deposits. Where desirable and technically feasible, the channels were straightened; river bends lengthened the waterway and increased the risk of logs being washed onto the bank and damaged, and they also made timber rafting more difficult. Exposed sections and bends were protected with timber revetments. In the bends of the watercourses, stone linings were constructed (Fig. 4). The passability of driven wood was ensured by raft sluices built into the weirs. Where rafts were to be assembled, binding stations with their own weirs (Bindwehre) were established.

Fig. 4. Bend on the Černá River below Zlatá Ktiš Pond, built from dressed stone blocks (photo: M. Bureš, May 2003)

Fig. 4. Bend on the Černá River below Zlatá Ktiš Pond, built from dressed stone blocks (photo: M. Bureš, May 2003)

In the forests, sites were constructed for storing logs. At the landing sites on the timber transport routes, timber depots (Legstätte) were established; there, splash dams (Rechen, Holzfangrechen) were installed to stop and remove timber from the water (Fig. 5) [5, 8]. By the mid-1780s, depots existed along the waterway to České Budějovice: on the Černá river at Ličov and in Ponholz near Blansko by Kaplice, on the Malše at Velešín, and at the southern edge of České Budějovice by the so-called Špitálský weir.

Fig. 5. Simple timber barrier a so called rechle (from the German Rechen, meaning rake) (source: Roučka, Z. Předválečnou Šumavou. Život – práce – krajina. Plzeň, 2006)

Fig. 5. Simple timber barrier a so called rechle (from the German Rechen, meaning rake) (source: Roučka, Z. Předválečnou Šumavou. Život – práce – krajina. Plzeň, 2006)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The construction of such an extensive and well-planned system took many years and generated a substantial body of written documents at the time. To the present day, a collection of documents has survived, albeit with significant gaps, covering the years 1780–1799. It is preserved in the State Regional Archive in Třeboň, within the archives of the Nové Hrady Estate [9]. Due to their fragmentary nature, the development of the navigation system can be followed in a more continuous manner only for the years 1780–1784. This period, however, represents a key stage in the system establishment.

The existing professional literature on the Buquoy navigation system is limited. A more comprehensive treatment of the topic is provided by Michal Bureš and Jan Pařez [5], and partially also by Jan and Erika Andreskovi [6] in the book Novohradské hory a podhůří (Gratzen Mountains and Foothills). Another team of authors, which included the author of this study, reviewed the history of the navigation system with a focus on the transport of logs; archaeologist Michal Bureš assessed the significance of the surviving parts of the system from the perspective of heritage conservation [1]. The present study builds on the research results published in the above-mentioned article. The history of timber floating in the Gratzen Mountains is also addressed by Jarmila Hansová in her study on splash dams [8]. Among smaller, older works, the article by Petr Jelínek [10] is noteworthy. A valuable account of the course of timber floating in the Gratzen Mountains during the 1930s is provided by Josef Klouda in his 1960 article [11].

The primary sources of information on the Buquoy navigation system remain the three publications by the Buquoy chief forest officer Theodor Wagner, published in 1895 [2], 1904 [3], and 1913 [4]. Existing literature therefore presents the system in its peak form at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The most abundant and information-rich source consists of the so-called construction reports (Bauberichte), submitted at weekly intervals by Johann Franz Riemer or another official supervising the construction of the navigation system. The reports primarily document the clearing of streams, the construction and, where necessary, repair of sluices, weirs, and revetments of streambeds and banks. They also contain information on the progress of floating both loose and bound timber. Through the construction reports, the owner of the estate, Count Johann Nepomuk Buquoy, received up-to-date information on the progress of the construction of the navigation system, while various matters were also submitted to him for decision, such as the 1783 proposal to establish a new reservoir. Many construction reports contain his decisions and instructions, his comments, as well as words of praise. The Count actively intervened in both the building of the system and the floating operation, and he demanded full commitment from his officials.

Occasionally, the construction reports are accompanied by appendices in the form of tabulated statements recording the work carried out over a given period (usually a week). These list the type and number of construction personnel (masons, carpenters, labourers, stone-blasters), the amounts of wages paid, etc. The most complete surviving set of documents relates to the floating of logs and rafts in April and May 1783.

Some other written documents also have considerable informational value – proposals or expert opinions – which touch on a wide range of aspects connected with the construction and operation of the navigation system, from the techniques of log tying to the question of securing a sufficient number of raftsmen, the financing of construction costs, and the organisation of forest management in accordance with the needs of timber floating. The extensive cartographic documentation from the second half of the 18th century, often accompanied by detailed textual annotations, is equally significant. This material is also preserved in the Nové Hrady Estate archive collection.

A significant source of information on the early stages of the navigation system is a typescript copy of an original 1795 report, held in the State Regional Archive in Třeboň within the collection of the Regional Water Management Development and Investment Centre in České Budějovice [7].

All the above-mentioned source material – consisting primarily of dozens of handwritten documents from the final quarter of the 18th century – first had to be read through to gain an overview of the range of topics it covers. From this body of material, information was selected that made it possible to compile a chronological outline of the beginnings of timber floating in the Gratzen Mountains. A number of assertions found in both the professional literature and the sources themselves were verified from a critical perspective (for example, the claim that rafts were first floated to Prague as early as 1783). To extract many of the detailed pieces of information, it was necessary to combine and compare data contained in individual sources – whether written documents or maps. A separate task involved arranging these individual pieces of information in chronological order, as the sources in the archival collection are not organised in a way that allows them to be read as a continuous narrative.

Given that the core of this study (the Results) explicitly rests on the processing and interpretation of primary source material, it would not have been feasible to cite every single piece of information, as this would require a reference after virtually every sentence – and frequently to two or more documents at once. Therefore, wherever sources are cited only in general terms, or where no other reference is provided, the information is drawn from the corpus of materials introduced above (construction reports and other written documents, maps) held in the Nové Hrady Estate archival collection, from which the vast majority of the data originates.

RESULTS

The year 1780

Construction of the navigation system began in 1778, following a thorough examination of Riemer’s proposal and the granting of official permission for the works. The Buquoy navigation system predated both of the renowned Šumava timber-floating canals – the Schwarzenberg Canal (under construction from 1789) and the Vchynicko–Tetovský Canal (under construction from 1800). In terms of technical design it was entirely unique, as it made it possible to operate timber rafting even on the low-capacity, narrow watercourses of the Gratzen Mountains.

A more continuous sequence of the fragmentarily preserved sources from the Nové Hrady Estate collection begins in 1780. By that time construction works were already well underway, and the Pohořský stream together with part of the Černá river had been modified to such an extent that from 9 to 13 April it was possible to float 955.5 (cubic) fathoms (note: the Czech sáh = fathom) of logs to the depot at Ličov (Litschau) below the confluence of the Černá and Pohořský stream. To gain an idea of how much timber this represents when converted into the cubic metres used today, it is important to bear in mind that these were so-called stacked cubic fathoms, that is, the volume of wood arranged into piles including the spaces between the logs. 955.5 stacked cubic fathoms corresponds to roughly 6,500 stacked m3. This approximate conversion is based on the cubic fathom defined by the Lower Austrian system of measures, which was in force in Bohemia in the 1780s. Under this system a cubic fathom equalled approximately 6.82 m3. The volume of the actual timber (expressed in so-called solid m3) was in fact two thirds to one half smaller. The logs were typically two or three feet long (a foot in the Lower Austrian system of measures corresponds to approximately one third of a metre) [12].

The waterway downstream of Ličov was being heavily modified with a view to extending the stretch navigable by log driving and introducing timber rafting. In all probability, during the summer months of 1780, Uhlišťský pond was constructed on Uhlišťský stream (Theodor Wagner, in a treatise from 1904, gives the year 1775). The contract for the construction of Uhlišťský pond was concluded in the spring (probably April 1780) with a certain Joseph Wagner of Stropnice for the sum of 1,200 gulden. The necessary tools – such as wheelbarrows, pickaxes, iron bars, augers, and hammers – as well as gunpowder for breaking rocks were to be supplied to him by the Buquoy estate administration. In 1780, splash dams were built at Ponholz [8]. From the construction reports we learn, among other things, of the intention to build splash dams at Velešín (April), of the cleaning of the lower course of the Pohořský stream, of modifications to the weirs along the lower reaches of the Černá (October), and of the construction of two sluices at the weirs by the paper mill (Papiermühl) near Blansko by Kaplice (end of 1780).

A relatively large space is devoted in the construction reports to this type of navigation-related construction work. It was carried out directly by the Buquoy estate administration, using its own carpenters (Zimmerleiten) and masons (Maurer), assisted by journeymen (Geßelle) and labourers (Handlanger), as well as stone-blasters (Steinschießer). They were paid for their work at weekly intervals. Part of the work was contracted out by the estate administration, as in the case of the construction of Uhlišťský pond. The Buquoys had sufficient construction timber available from their own estate forests. The construction of the navigation system was ideally to be financed from the proceeds of timber sales. In the early 1780s the Buquoy family traded in timber from forest districts outside the Gratzen Mountains; for 1782 there is an explicit reference to the sale of timber from the forest districts of the Libějovice estate, which the Buquoys also held at that time. Another potential financial source was the revenue from the grain trade, or income flowing into the manorial treasury from feudal rents. If the navigation system was to pay for itself, it had to be completed as quickly as possible.

The year 1781

In the spring of 1781, from 23 to 28 April, logs were floated to Ličov, to the paper mill near Blansko, and to Ponholz. Thus, in that year log driving was extended along the entire Černá river from its confluence with the Pohořský stream. At all three timber depots a total of 1,471.5 fathoms of logs were hauled out. Most of the timber was floated to Ponholz – 1,102 fathoms. The first raft-floating trials probably also took place no later than the autumn of 1781. The surviving construction reports from November inform us only about the floating of logs, to a total volume of almost 1,200 logs, to the (manorial) Lužnice sawmill (Luschnitzer Breth-Saag, Luschnitzer Saag Mühl) situated on the Pohořský stream near Terčí (today Pohorská) Ves. The logs were apparently floated from several locations along the upper course of the Pohořský stream, possibly including the so-called Baron Bridge (Baronwehr) below Pohořský pond, to which the starting point of timber rafting was later shifted [3]. The surviving sources indicate that at least until 1795, rafts were floated from Lužnice sawmill, whereas logs were floated on the upper, steep course of the Pohořský stream [7]. Lužnice sawmill was located near Terčí Ves (Fig. 6), which is why the timber depot there is commonly referred to as Terčí Ves depot (Theresiendorfer Legstatt). At Terčí Ves, splash dams were installed to allow logs to be pulled out of water. In the depot, timber could properly dry before being floated further to its destination.

Fig. 6. Location of Lužnice sawmill (Herrschaftliche Luschnitzer Saag Mühl) near Terčí (nowadays Pohorská) Ves (source: State Regional Archives in Třeboň, Satellite Office Třeboň, archival fond Nové Hrady Estate, map No. 2 759)

Fig. 6. Location of Lužnice sawmill (Herrschaftliche Luschnitzer Saag Mühl) near Terčí (nowadays Pohorská) Ves (source: State Regional Archives in Třeboň, Satellite Office Třeboň, archival fond Nové Hrady Estate, map No. 2 759)

The year 1782

In 1782, logs were probably floated on the Malše river on a large scale for the first time. From 8 to 19 April, 2,115.75 fathoms of timber were floated to the depot in Velešín. From 22 to 28 May, timber was floated to Ličov (214 fathoms) and Ponholz (352 fathoms). For 1782, the first autumn float is also documented, which took place from 4 to 9 November; logs were then transported to Ličov (319.25 fathoms) and Ponholz (258.5 fathoms).

The first reports of trial timber rafting on the Pohořský stream and the Černá date from the spring of 1782, specifically on the stretch from the timber depot at Terčí Ves, where logs were floated individually, to Ponholz. The sources describe a series of four timber rafting trials, which took place from late April to the first half of May. During the fourth rafting, carried out on 13 May, 13,156 Viennese fathoms of timber were successfully floated from Terčí Ves to Ponholz. The raft arrived in Ponholz to great admiration from the onlookers; the route to České Budějovice was open. For 1783, it was planned to float rafts to Prague, and preparations for this were underway. At the beginning of December 1782, leading officials of the Nové Hrady Estate met, with Riemer and Count Buquoy himself in attendance, to discuss preparations for log driving and timber rafting in 1783. They addressed the establishment of a timber depot in České Budějovice, the demand for logs, the organisation of tree felling for log driving and rafts, and the financing of further development of the navigation system. It was resolved to construct a timber depot above Budějovice at the so-called Špitálský weir (Spitalwehr), with the land to be leased rather than purchased. At the same time, during the winter, possibilities for selling timber in Budějovice were to be explored. Even in 1782, construction and transport work continued along the waterway. The cleaning of streambeds and the construction and repair of wooden bank reinforcements also continued.

The year 1783

In the history of the Buquoy navigation system, 1783 holds a prominent position. From 7 to 15 April, the first transport of logs to České Budějovice took place. At the newly constructed timber depot near Špitálský weir, 1,232 fathoms of wood were removed from the water. The timber had been floated from the depot in nearby Velešín. It consisted of wood (or part of it) that had been floated from the Gratzen Mountains to Velešín the previous year, for which buyers apparently could not be found.

The second transport of logs to České Budějovice took place from 23 April to 13 May. It was the first transport of logs to Budějovice directly from the forests of the Gratzen Mountains. On the Pohořský stream, the logs were thrown into the water at several locations on 23 and 24 April. By 13 May, all floated timber had been stacked into piles at the České Budějovice depot. In total, it amounted to 1,933 fathoms, partly of hardwood but predominantly softwood logs. Simultaneously with the transport to České Budějovice, timber was also floated to Ponholz. At the local splash dams, 492 fathoms of logs were floated. The costs of transporting logs to České Budějovice and Ponholz in the period from 23 April to 13 May amounted to 1,575 gulden 44 kreuzer, while the net profit from the transport was 2,697 gulden 1 kreuzer.

From May 1783, we have reports of two timber rafting trials, which also had a purely practical purpose, as they were used to deliver timber for the construction of sluices at the end of the route just before České Budějovice. The first trial timber rafting took place from 6 to 8 May 1783. The transport ran from Terčí Ves to the mill weir in Plav. The timber rafting coincided in time with the log driving. Both operations were uncoordinated at the time, and, as Riemer notes in his report of 11 May 1783, the rafts floated from Doudleby to the mill weir at Plav over accumulated logs. The second timber rafting (from Terčí Ves) took place from 15 to 19 May 1783, again aimed at the mill weir below Plav, where construction timber for the sluices was delivered. In both timber rafting operations, three smaller rafts of construction timber were dispatched from Terčí Ves, which were joined into one large raft at the paper mill near Blansko by Kaplice. It consisted of 10 rafts, each made up of eight or nine logs. Timber rafting of the same dimensions took place at the beginning of June 1783, this time reaching as far as Vidov. The floated construction timber was intended for the building of sluices at Plav, Vidov, and Špitálský weir, as well as for the construction of a small house for the overseer at the Budějovice timber depot.

In 1783 there was a severe drought; moreover, the previous year had also been low in rainfall. Perhaps it was the lack of water that prompted Riemer at the end of May to submit a proposal for the construction of a new reservoir, this time on the Černá. After its creation, Riemer notes, it will no longer be necessary to wait for the Pohořský stream to refill before the next timber rafting. In periods of low water, the waters from both reservoirs could be combined. The text does not specify which reservoir is being referred to. Most probably, it was the later-disappeared Leberharter reservoir, whose existence is documented by an undated map, probably produced shortly after 1795 (Fig. 7). This reservoir was located at the confluence of the Černá and Huťský stream. The second reservoir on the Černá – Zlatá Ktiš – was constructed later, between 1789 and 1796 (according to Theodor Wagner in his 1904 publication). In 1783, the construction of the reservoir was apparently abandoned, as the proposal for its establishment was repeated in an extensive report by the Buquoy estate management office at the beginning of February 1784.

Fig. 7. Situation on the upper reaches of the Černá River in the second half of the 1790s; the map shows the later defunct Leberhart Reservoir (source: State Regional Archives in Třeboň, Satellite Office Třeboň, archival fond Nové Hrady Estate, map No. 2 759)

Fig. 7. Situation on the upper reaches of the Černá River in the second half of the 1790s; the map shows the later defunct Leberhart Reservoir (source: State Regional Archives in Třeboň, Satellite Office Třeboň, archival fond Nové Hrady Estate, map No. 2 759)

The first rafts to Prague – albeit in limited quantities – were probably floated in the autumn of 1783. During the summer, drought hindered the construction of sluices at the end of the route to České Budějovice, namely at Plav, Vidov, and Špitálský weir; due to low water levels, it was not possible to float construction timber in rafts from the Gratzen Mountains. Although the studied sources do not contain reports describing timber rafting from autumn 1783, Count Buquoy’s order of 14 January 1784 suggests that at least trial runs to Prague must have taken place in autumn 1783. 1783 is given as the start of timber rafting in the 1795 report on the navigation system [7], as well as in the commentary on a map of the system produced shortly after 1795 (in the inventory compiled for the maps from the archival fond Nové Hrady Estate, this map is No. 2,760).

The beginning of the navigation work on the Černá river, in the section above its confluence with the Pohořský stream, also falls within 1783. In July 1783, cleaning of the Černá was to commence so that it could subsequently be made navigable, which was carried out in 1785 (according to the commentary on map No. 2,760, held in the archival fond Nové Hrady Estate).

The year 1784 and the subsequent fate of the navigation system

The first explicit mention of rafting from the Gratzen Mountains through České Budějovice onwards to Prague dates from June 1784. In the report of 4 June, Riemer describes a raft consisting of 400 logs travelling to Prague, which, according to his estimate, was to arrive on 14 or 15 June. It was to be loaded with fathom timber from the Libějovice estate of the Buquoy family. A report dated 7 September 1784, dealing with the preparations for timber rafting in 1785, suggests that rafts were again floated in limited quantities that year, and that timber rafting had not yet brought the profit expected by the Count. The entire business struggled with a shortage of raftsmen, and there were evidently some difficulties in gathering a sufficient number of logs to be floated in order to make full use of the navigation system capacity.

Despite the slow start for timber rafting, 1783 and 1784 marked a decisive turning point in the history of the Buquoy navigation system. The successful opening of the waterway from the Gratzen Mountains to České Budějovice crowned the many years of effort by Count Buquoy and his staff – engineer Johann Franz Riemer, the estate officials (administrative, financial, and forestry), and other participants – raftsmen, craftsmen (stonemasons and carpenters), and hired labourers (stone blasters and general assistants).

In the following years, the navigation system was further expanded. The reservoir on the Černá, proposed in 1783, must have been constructed either in 1784 or 1785, since by 1785 logs were already to be floated on the upper reaches of the Černá, and rafts from 1792. At the end of the 1780s, construction began on a second reservoir on the Černá – Zlatá Ktiš – which was finally completed shortly after 1795. At the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Lužný, Huťský, and Tisový streams were made navigable. On the last two, reservoirs of the same name were built.

The construction and operation of the navigation system transformed the previously sparsely settled forests of the Gratzen Mountains into a cultural landscape interwoven with a network of entirely new mountain settlements. The navigation system functioned and prospered throughout the 19th century and nearly the entire first half of the 20th century. Timber rafting was carried out until the summer of 1938. Logs were verifiably floated even in the first half of the 1940s [1, 10].

DISCUSSION

The study builds on previous research on the Buquoy navigation system, focusing on the initial years of its existence. It provides a range of new insights and, in part, clarifies information recorded in the literature, primarily under the influence of Theodor Wagner’s works from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

From the surviving sources, it is possible to fairly clearly trace the gradual expansion of the waterway between 1780 and 1783. By 1783, the Buquoy navigation system for both loose logs and rafts had reached České Budějovice, which corresponds with the data in Wagner’s writings and the professional literature. The research also allows the construction of Uhlišťský pond to be dated to 1780, whereas Wagner gives the year 1776 [3]. The sources further indicate that in its early years, the system included the manorial (Buquoy) Velký Ličovský pond (in contemporary sources referred to as Seifritzteich or Seifriedtsteich), which was only later replaced by Kancléřský pond leased from the Český Krumlov prelature.

Thanks in particular to the set of sources from the Nové Hrady Estate archival fond, it was possible to shed light on the organisational and institutional background of the construction and operation of the navigation system – for example, the involvement of the manorial offices and their staff, as well as the active role of Count Buquoy. The information on the first timber rafting trial is particularly valuable, as it documents the technical issues faced by the first raftsmen. Documents from 1783 and 1784 bear witness to the difficult beginnings of timber rafting and its insufficient profitability during the first years of the system’s operation.

The limits of the research were set by the fragmentary and ultimately rather restricted source base, so it was not possible to fully resolve a number of questions, and some remain open. This applies, for example, to the question of whether, and to what extent, loose logs was already being floated on the Pohořský stream and the Černá before 1780. Similarly, we know practically nothing about the course and scale of the raft operations in the autumn of 1783. We have only very fragmentary information at our disposal regarding the making of the Černá navigable upstream of its confluence with the Pohořský stream, as well as regarding the construction of the earliest reservoir on the Černá, the so-called Leberhart reservoir. Given that the key archival fond, Nové Hrady Estate, has not yet been processed, it is entirely possible that it still contains documents that could shed more light on the history of the navigation system. The extensive – though fragmentarily preserved – source material could not be fully utilised in its entirety. More time would be required for that, as well as close cooperation with other specialists, especially archaeologists who could interpret the information relating to the technical aspects of the system’s construction, and experts in forest management.

CONCLUSION

In the last quarter of the 18th century, a unique navigation system was constructed on the watercourses of the Gratzen Mountains and their foothills, enabling the transport of both loose logs and bound timber on low-discharge streams with a considerable head. The key part of the navigation system lay within the Nové Hrady Estate, owned by the noble Buquoy family. It was created according to a design by the engineer Johann Franz Riemer, who oversaw the construction and played a decisive role in shaping the further development of the navigation system into the form it acquired at the end of the 18th century, in which it then – albeit with certain modifications – endured until the first half of the twentieth century. The principal timber-floating route of the system consisted of the Pohořský stream, the Černá, and the Malše, which flows into the Vltava in České Budějovice.

Construction of the navigation system began at the end of the 1770s. By 1783 the system was ready for the floating of logs and rafts to České Budějovice; from there the rafts continued via České Budějovice and Týn nad Vltavou to Prague. In 1783 the navigation system comprised the Pohořský stream, the Černá from its confluence with the Pohořský stream, and the Malše. At that time three ponds (reservoirs) existed: Pohořský pond (second half of the 1770s) and Uhlišťský pond (1780), both constructed on the streams of the same name, and Velký Ličovský pond below the confluence of the Pohořský stream and the Černá, located outside the main route. Wood depots along the route were located in Terčí (Pohorská) Ves, Ličov, Ponholz, Velešín, and České Budějovice. Whereas logs were floated to the respective depots directly from the uppermost sections of the waterway, timber rafting was somewhat more complex. Logs were driven from the forest to the depot in Terčí Ves, where they were tied together into rafts. At the paper mill near Blansko several rafts floating from Terčí Ves were tied together into one long unit, which then continued to České Budějovice.

From 1785, logs were also floated on the upper course of the Černá, that is, upstream of its confluence with the Pohořský stream. This was preceded by making the Černá navigable and the construction of another reservoir on the Černá, probably the later-disappeared Leberhart reservoir at the confluence of the Černá and the Huťský stream. Due to a lack of sources, we can only form a basic picture of how the navigation system was expanded during the 1780s and 1790s. Subsequent development took the form of making higher reaches of the Černá and its tributaries – the Lužný, Huťský, and Tisový streams – navigable. From 1792, rafts were also to be floated on the upper reaches of the Černá. This is an interesting piece of information, as reports of this navigation are absent in sources from the late 19th and first half of the 20th century. In 1796, Zlatá Ktiš on the Černá was completed, and around 1800 ponds on the Huťský and Tisový streams were established (Mlýnský pond on Lužný stream was older). With this, under the supervision of engineer Riemer, the construction of the entire navigation system was completed.

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out as part of the NAKI III grant project No. DH23P03OVV007 Complex Approaches to the Identification, Protection and Maintenance of Historical Water Retention and Distribution Systems in Mountain Areas of the Czech Republic with regard to Heritage Conservation. I would like to take this opportunity to thank both reviewers – Ing. Magdalena Nesládková and Radek Šťovíček.

The Czech version of this article was peer-reviewed, the English version was translated from the Czech original by Environmental Translation Ltd.