Let us return once more – and for the last time – to Jáchymov, a small town nestled in a deep, forested valley of the Ore Mountains. It lies somewhat hidden, yet in an excellent strategic location, within walking distance of Ostrov, Klínovec, and Boží Dar (in German Gottesgab; Fig. 1) – the highest town in the Czech Republic, situated right on the border crossing to Oberwiesenthal in Saxony (Fig. 2). From Boží Dar, one can also continue into Božídarské rašeliniště Nature Reserve.

Fig. 1. Boží Dar, Ježíšek post office

Fig. 1. Boží Dar, Ježíšek post office

Fig. 2. View from Klínovec to Saxon Oberwiesenthal

Fig. 2. View from Klínovec to Saxon Oberwiesenthal

However, Jáchymov boasts many other remarkable firsts and renowned “bests”. It was here that the world’s first radon spa was founded, centred around the construction of the grand Radium Kurhaus (author’s note: today’s Radium Palace) – once one of the most luxurious hotels in Europe (Fig. 3). The origins of the spa are closely tied to the discoveries of Marie Curie, the first woman to earn a doctorate from the Sorbonne and to receive two Nobel Prizes. In 1520, Jáchymov also became home to the first pharmacy in Bohemia. To this day, the town remains unique worldwide for its use of brachytherapy (“Jáchymov boxes”, BRT), a specialized treatment method found nowhere else. All these remarkable Jáchymov milestones have already been discussed in detail in the April and especially August issues of VTEI this year [1, 2]. So now, let us turn our attention to another local marvel that literally shaped Jáchymov’s history – Svornost Mine. And let us start from the very beginning.

Fig. 3. Radium Palace

Fig. 3. Radium Palace

The spa season

Even a hundred years after Marie Curie’s visit to Jáchymov, it still pays to be in the right place at the right time [see more in 2]. For instance, visiting Jáchymov Spa in the second half of May this year offered a special opportunity: on Saturday, 24th May, guests could attend the ceremonial opening of the 119th spa season and meet the leadership of the town, the spa, and Svornost mine, including an invitation to the international conference The legacy of Marie Curie in Jáchymov Spa and the 100th anniversary of her visit [3]. The highlight of the day’s festivities was the blessing of the springs and wishes for a successful spa season delivered by Father Milan Geiger, followed by speeches from František Holý, the Mayor of Jáchymov, Gustav Žaludek, Director of the Spa, and Martin Přibil, Director of Svornost Mine. The ceremony also featured mine workers in traditional uniforms (Fig. 4). Svornost Mine – one of Jáchymov’s defining landmarks and enduring symbols – is, in many

ways, ever-present in the town. Without its “water of life,” there would be neither patients nor visitors, no spa at all. Let us therefore take a closer look at its history.

Fig. 4. Opening of the spa season (May 2025)

Fig. 4. Opening of the spa season (May 2025)

Mining region

The Jáchymov region forms an important part of the Ore Mountain Mining Region (Erzgebirge in German), which is composed of 22 areas. Five of these are located on the Czech side: Jáchymov Mining Landscape, Abertamy – Boží Dar – Horní Blatná Mining Landscape, the Red Tower of Death, Krupka Mining Landscape, and Mědník Mining Landscape, while the remaining 17 lie across the border in Saxony. Together, these sites bear powerful witness to the immense influence that mining and ore processing on both sides of the mountains had on the global development of mining and metallurgy. Over 800 years of almost continuous extraction and processing of ores have shaped in the Ore Mountains a truly unique mining landscape, characterized by an exceptional concentration of technical monuments whose variety and density are unparalleled anywhere in the world. These heritage sites document the methods of mining and refining various types of ores from the 12th to the 20th century – primarily silver, tin, cobalt, arsenic, nickel, iron, and, in more recent times, uranium.

Svornost Mine

Svornost Mine (Fig. 5) undoubtedly has its own genius loci and is regarded in Jáchymov as a true “family treasure”. It dates back to 1518, although at that time the shaft bore the name Konstantin. It was excavated in the upper part of the town along the newly discovered, rich silver vein Stella, which had been found in Jáchymov in 1516. For the miners of that era, the most important task was the extraction of ore, primarily silver in this case, from the vein. In the 16th century, this meant purely manual labour – the driving of adits, galleries, and shafts was most often done using only a hammer and pick. So, how was the ore actually extracted? The miner would strike the back end of a pick with his hammer so that the tip of the pick drove into the rock, breaking off fragments of stone. This method of extraction gave the adit its characteristic shape, still visible in old mine workings today. It is assumed that during a single shift, a miner wore out 30 to 40 picks. These were loosely fitted into their handles, allowing the miner to replace them easily with new ones. The blunted tools had to be resharpened daily in the mining smithy (author’s note: this information comes from a tour of the exhibition in the former Royal Mint).

Fig. 5. Svornost Mine (August 2024)

Fig. 5. Svornost Mine (August 2024)

However, after this demanding extraction, the silver-bearing ore usually contained no more than 0.1 % silver, and any further processing to obtain the metal from the ore was at that time extremely complex and costly. Considering that between 1516 and 1554, some 250,000 kilograms of silver were mined in Jáchymov by this method, and that the mine contains more than 120 kilometres of galleries [5], the hard work of the miners of that era still commands great respect today. As early as 1520, thanks to silver mining, Jáchymov was elevated to the status of a free mining town. In 1530, the shaft was renamed Svornost (German Einigkeit – “Unity”) in commemoration of the reconciliation between the mine’s two former rival owners.

Svornost Mine is also the world’s first uranium mine. During its operation, silver was extracted here first, followed later by cobalt and other ores, and from 1853 onwards by uraninite, which was used in the local factory producing luminous paints for glass and porcelain (author’s note: this uranium colour factory in Jáchymov operated successfully for almost one hundred years, but was demolished at the beginning of the Second World War). It is also the oldest functioning mine in Europe. Since 1906, it has been used to obtain radioactive water for spa purposes. This water, thousands of years old, originates from the depths

of the Jáchymov bedrock and becomes naturally enriched with radon; thanks to its rich chemical composition, it has healing properties.

Geological perspective

From a geological perspective, the Jáchymov deposit was a vein-type deposit, with the fillings of these veins composed of ores of silver, arsenic, cobalt, nickel, bismuth, and uranium. They were formed by the penetration of hydrothermal solutions from the underlying magma into fissures created within the older mantle of metamorphic rocks, consisting mainly of phyllites. This process resulted in the formation of two principal vein systems within the deposit: (1) east–west-oriented veins, known as morning veins, and (2) north–south-oriented veins, referred to as midnight veins.

- The east–west-oriented morning veins are weakly mineralised or barren faults that roughly follow the strike of the phyllite sequence, though they differ in dip. Their fillings consist of clay and mylonitised (author’s note: consolidated) fragments of the surrounding rocks. Manifestations of hydrothermal mineralisation are sporadic; only in the vicinity of intersections with the north–south-oriented midnight veins does more intense mineralisation occur along these veins. This vein system is characterised by stable structural conditions. The veins reach lengths of up to one kilometre, and their thickness most

commonly ranges between 0.5 and 1 metre [4].

- The north–south-oriented midnight veins are far more numerous and more richly mineralised. However, the structural conditions of this system are much less consistent than those of the morning veins. The midnight veins are generally only a few hundred metres long, and their thickness varies considerably. Along the same vein, thickness often fluctuates over very short distances – from just a few centimetres to over a metre – averaging between 10 and 30 centimetres. The vein filling is mostly composed of dolomite, calcite, and quartz, while in some sections of the veins, fluorite is the dominant mineral. Uranium ore – pitchblende, or uraninite – was extracted in Jáchymov from more than 400 veins, with a total vein surface area of 8,000,000 m². However, the average thickness of the uranium mineralisation was only 0.15 mm, making it a poor deposit with low productivity [4].

Hydrogeological perspective

The presence of fault lines, minor tectonic features, and vein structures, which are predominantly hydraulically permeable, favourably influences the infiltration of surface water into the rock complex. From a hydrogeological perspective, the groundwater of the Jáchymov area can be divided into two groups as well: (1) cold waters and (2) thermal waters.

- Cold groundwater, circulating within the metamorphic rocks, is discharged both through surface springs and through outflows in the mine workings. The temperature of these springs corresponds to the depth at which they emerge. Springs at higher levels have lower temperatures, which increase with depth. More substantial water outflows are associated with major open fault lines and vein structures, which enable more active contact of water between surface and deeper parts of the metamorphic complex [4].

- Thermal groundwater is represented by radioactive thermal springs. All currently known radioactive thermal springs in Jáchymov emerge at the twelfth level of Svornost Mine, roughly 500 metres underground, which corresponds to the zone of greatest artificial lowering of the groundwater table. Some of these thermal springs were tapped during geological exploration

(e.g., C–1), while others were intersected during mining operations (e.g., Curie) [4].

Following their exposure through mining activities, a system of several springs developed here, which are hydraulically connected and share the same water source and mineralisation, as well as similar chemical composition and nearly identical temperatures. All the springs are also characterised by pronounced radioactivity, which, together with other physicochemical properties of the water, creates a globally unique and extremely valuable natural medicinal resource.

Radioactive healing springs

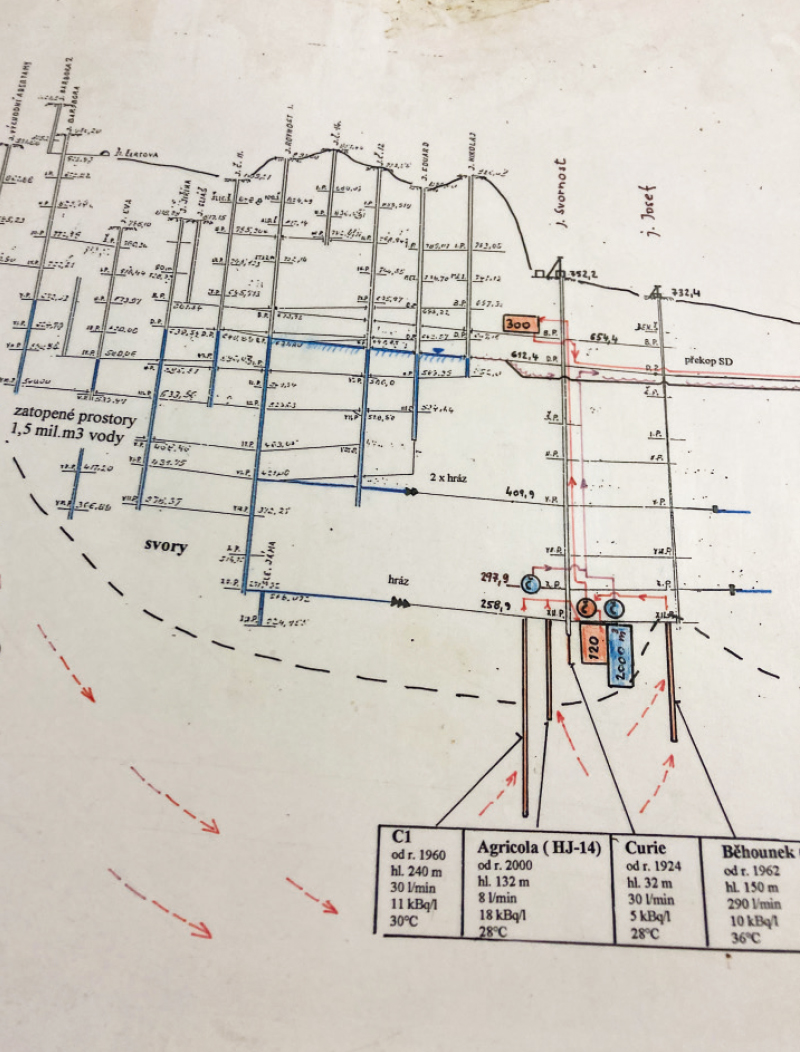

For balneotherapy, four springs are currently used in Jáchymov, as shown in the map from Svornost Mine (Fig. 6):

- Curie Spring is the oldest. It was discovered on 12 March 1864 during further shaft excavation at a depth of approximately 30 metres below the twelfth level. The original discharge of the spring was about 400 l/min, with a temperature of 22.5 °C. (Author’s note: by comparison, the current discharge is around 30 l/min, with an average temperature of 28.8 °C and an average activity of 5.7 kBq/l.) At the time of its discovery, the spring was so powerful that it completely flooded the shaft, reaching up to 300 m along the Daniel adit on the sixth level [4]. Initially, this was more of a hindrance to the miners, as it obstructed their work, and they attempted to pump the water out. However, like their predecessors 300 years earlier, they soon experienced the beneficial effects of this mine water, which relieved the aches of their fatigued bodies. A significant contribution to this understanding came from the mine manager at the time, Josef Štěp; he, together with the physician Leopold Gottlieb, who, building on the scientific discoveries of the Curie’s, investigated the effects of radioactive waters (see [2] for more), initiated a new era

in Jáchymov’s history, and laid the foundations of local balneology. In honour of Marie Curie, the spring was later named after her. It has been officially used for spa baths since 1924. - C–1 Spring was discovered during geological exploration in 1960. It was drilled from the twelfth level of Svornost Mine to a depth of 240 m. The spring has an average discharge of around 40 l/min, a temperature of approximately 29.6 °C, and an average activity of 11.5 kBq/l [4].

- Academician Běhounek Spring (author’s note: often referred to simply as Běhounek) (Fig. 7) is the most important source of radioactive water for the spa operation. It was discovered as a result of geological exploration carried out between 1962 and 1963, during which nine boreholes were drilled at the twelfth level of Svornost Mine. One of these (borehole HG–1, at a depth of 152.7 m) intercepted a powerful spring with a discharge of 570 l/min and a temperature of 28.6 °C. Its radon concentration was 10 kBq/l [4]. The spring was named in honour of Dr František Běhounek, a prominent Czech physicist and chemist, who had been a student of Marie Curie at the Sorbonne in his youth and maintained a warm connection to Jáchymov. Together with Curie and C–1 springs, Academician Běhounek Spring provided a sufficient supply of medicinal radioactive water for baths for patients in the treatment houses, thereby contributing to the intensive development of the spa industry in Jáchymov.

- Agricola Spring is the newest of the local springs, discovered in 2000 by borehole HJ–14 at a depth of 132 m. It has a discharge of 5 l/min and a temperature of 28 °C, with a radon concentration of 25 kBq/l [3]. This spring is also named after a notable historical figure associated with Jáchymov. Georgius Agricola, born Georg Bauer, worked in the 16th century in Jáchymov as the town physician. In addition to studying medicine in Italy, he was educated at German universities and also engaged in mineralogy, mining, and metallurgy. Presumably for this reason, he focused particularly on the health of miners and the treatment of their specific illnesses, as well as on the therapeutic properties of the local waters and minerals. His scientific work laid the foundations for modern mineralogy and the sciences related to mining and metallurgical activities. A commemorative plaque in the spa honours him as well (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6. Svornost Mine, spring map

Fig. 6. Svornost Mine, spring map

Fig. 7. Svornost Mine, Academician Běhounek Spring

Fig. 7. Svornost Mine, Academician Běhounek Spring

Fig. 8. G. Agricola memorial plaque in Jáchymov

Fig. 8. G. Agricola memorial plaque in Jáchymov

All four of these springs are still used for treatment today, with patients receiving a mixture of their waters during baths. The water is conveyed via pipelines to a radioactive water retention tank with a capacity of 150 m³, built into the rock massif at the twelfth level of Svornost Mine. From this tank, the water is pumped into an accumulation reservoir with a capacity of 300 m³ located on the Barbora level, 100 m below the surface. From there, it is transported by gravity along the Daniel level through a pipeline nearly 3 km long to the individual balneotherapy facilities of the treatment spa. The entire system of collection and transport of radioactive water from Svornost Mine to the points of use is closed to prevent the escape of radon from the water [4].

Half a kilometre underground

Entering the depths of Svornost Mine – that is, descending to the twelfth level, roughly 500 metres underground – is not entirely impossible for patients or visitors to the Jáchymov spa. Guided tours with expert commentary are occasionally organised. All that is required is sturdy footwear and warm clothing – mine staff then provide a blue protective coat and a helmet with a headlamp – and perhaps a little courage, as visitors voluntarily plunge in a metal cage through darkness and cold, icy water dripping on them, while the hoist wails deafeningly. But it is worth it. Below, only a few technical instructions remain on very wellworn doors (Fig. 9), marking the end of the familiar, civilised world. The tunnels are dark, damp, and cold, and each person is truly on their own here (Fig. 10). Yet, when illuminated by the headlamps on the helmets, the walls seem to come alive, playing with all the colours of a wide variety of ores and minerals – limestone, sulphur, iron, as well as silver, tin, cobalt, and others (Fig. 11). After all, Jáchymov hosts 17 metal-bearing ores and over 400 different minerals. Our guide adds that this makes Svornost Mine the richest geological site in the world. Complex stalactites are also often seen here, thriving in the cold, damp conditions (Fig. 12).

Fig. 9. Svornost Mine after descending to the 12th level underground

Fig. 9. Svornost Mine after descending to the 12th level underground

Fig. 10. Most tunnels in Svornost Mine are not illuminated, so a helmet with a headlamp is very useful

Fig. 10. Most tunnels in Svornost Mine are not illuminated, so a helmet with a headlamp is very useful

Fig. 11. Svornost Mine – the richest geological site in the world

Fig. 11. Svornost Mine – the richest geological site in the world

Fig. 12. Rich speleothem decoration

Fig. 12. Rich speleothem decoration

One of the few permanently illuminated spots is the altar dedicated to Saint Barbara, the patron saint of all miners (Fig. 13). Miners and mine workers came here to pray, and after the end of the Second World War and during the 1950s, political prisoners also prayed here while working in the uranium mines. The tiny chapel is therefore carefully maintained at all times, and even contains flowers.

Fig. 13. St Barbora Chapel in Svornost Mine

Fig. 13. St Barbora Chapel in Svornost Mine

The mine tour continues through more dark tunnels until the guide stops at a large mining installation with a tank and Academician Běhounek Spring (Fig. 14). From this point, the richest of the four springs is distributed to the various spa buildings throughout Jáchymov. In one of the side tunnels, the original mine carts and parts of historic pumps are still on display (Figs. 15a, b).

Fig. 14. A mine employee pumps Běhounek Spring into the test basin

Fig. 14. A mine employee pumps Běhounek Spring into the test basin

Fig. 15 a, b. Original carts and pump components

Fig. 15 a, b. Original carts and pump components

The circuit of the twelfth level of Svornost Mine lasts only about an hour, after which it is back into the metal hoist cage heading upwards – towards light, warmth, and fresh air. Looking back at the upper part of the mine, an interesting detail comes into view: a propeller that keeps turning (Fig. 16). Indeed, we have been in the oldest functioning mine in Europe and the world’s first uranium mine (Fig. 17).

Fig. 16. The Svornost Mine propeller

Fig. 16. The Svornost Mine propeller

Fig. 17. The author of the text was also 57 when she went down Svornost Mine; for F. Běhounek definitely a “Granny” (August 2024)

Fig. 17. The author of the text was also 57 when she went down Svornost Mine; for F. Běhounek definitely a “Granny” (August 2024)

The “Granny” went down

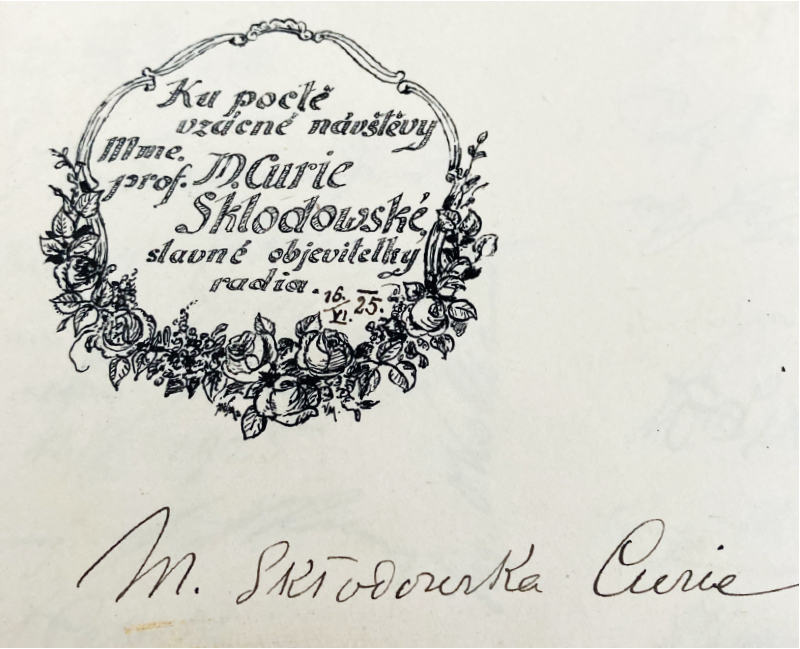

Here, a historical aside is in order. As mentioned in the August issue of VTEI [2], Marie Curie visited Jáchymov in June 1925. She spent several days there and was accommodated at the Radium Palace Hotel. Her guide at the time included the aforementioned František Běhounek, her student and young collaborator from the Sorbonne, who was very familiar with Jáchymov. As part of a conference held this June to celebrate the 100th anniversary of this visit [3], Professor Ing. Tomáš Čechák, CSc., from CTU shared a charming anecdote from her time in the town. Academician Běhounek reportedly recalled Madame Curie as follows: “On 17 June, the Granny descended into Svornost Mine. I was 26 years old, she was 57, yet she went down. She humbly accepted the greasy hat that had previously been worn by God knows who, and signed the visitors’ book there.” (Author’s note: this visitors’ book was on display for viewing during the aforementioned conference, see Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Marie Curie’s signature

It should be noted that the 57-year-old “Granny” (bábinka), as the young Běhounek called Marie Curie, repeatedly shocked him with her boundless energy and curiosity. At her request, for example, they set out for the highest peak of the Ore Mountains, Klínovec (1,244 m a.s.l.), and she then insisted that they return to Jáchymov on foot, because she wanted to “breathe in the fresh mountain air.” It is said that her Czech entourage could barely keep up with her at the time.

Adit No. 1

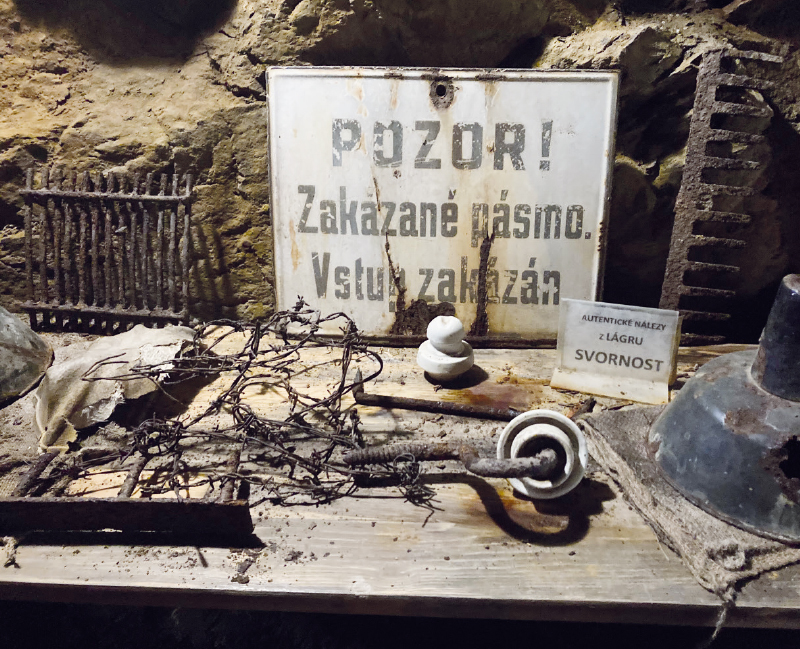

Just about 100 metres from Svornost Mine, in the direction of the centre of Jáchymov, lies Adit No. 1. Although it is near the surface, it is still cool inside. The adit is 260 m long and was driven in 1952 to verify uranium mineralisation. Silver was also mined here, from a silver vein called Jan Evangelista. Unlike Svornost, its tunnels are illuminated, so remnants of the silver vein are still visible on the walls (Fig. 19). Also on display are finds from Svornost and Jáchymov labour camps from the period 1949–1961, that is, from the “harsh” years when tens of thousands of political prisoners, sentenced to long terms, were forced to work in ten local concentration camps (Fig. 20). A reminder of them are the so-called katry (Fig. 21), massive metal grilles used to confine prisoners underground (author’s note: from this term, the Czech expression “sedět za katrem” – to be in prison – later emerged).

Fig. 19. Adit No. 1

Fig. 19. Adit No. 1

Fig. 20. Original objects from the Jáchymov labour camps

Fig. 20. Original objects from the Jáchymov labour camps

Fig. 21. Adit No. 1, metal grille

Fig. 21. Adit No. 1, metal grille

Jáchymov cemetery

A lasting reminder of the political prisoners in Jáchymov is also the local cemetery beneath the Church of All Saints, known as the Hospital Church (Fig. 22). It was established between 1516 and 1520, making it the oldest functioning historic building in the town. Why is it called Hospital? Because, from 1530 onwards, a municipal hospital stood next to the church, operating for over 400 years. In 1955 it was completely destroyed by fire and was never rebuilt; today, an urn grove occupies its site.

Fig. 22. Hospital Church

Fig. 22. Hospital Church

While the tombstones in some parts of the cemetery are already crumbling and gradually being reclaimed by nature, the graves of former miners and political prisoners are carefully maintained as a testament to the nation’s memory (Fig. 23). In the Ore Mountains, and especially in Jáchymov, one is often struck by the thought of how turbulent and “harsh” (krušný) the wartime and postwar periods must have been here, with concentration camps and forced labour for political prisoners. However, the Czech name of the mountains (Krušné) comes from the verb krušit, meaning “to mine,” and thus refers to this rich mining region, crisscrossed with hundreds of kilometres of underground adits; it has nothing to do with hardship or suffering.

Fig. 23. Grave of Jáchymov prisoners

Fig. 23. Grave of Jáchymov prisoners

Jáchymov levels

After uranium mining at Svornost ended in 1964, the mine was transferred to Jáchymov Spa and has since been used solely for pumping radon water for therapeutic purposes and for operating the radioactive waste repository managed by the State Office for Nuclear Safety. In 1979, reconstruction of the mine began, alongside the driving of the New Svornost Drainage Adit (author’s note: information from a lecture by the director of Jáchymov Spa, MUDr. Jindřich Maršík, MBA, at the conference on 12 June 2025; see [3]) (Fig. 24). Today, it is hard to believe that, after mining ended, the area around the mine was completely covered with enormous spoil heaps from the underground workings, and that the entire valley was filled with mounds of stone. After six decades, however, the land is once again green with forest, and the restored landscape presents a welcoming face. The only remnants of the ever-present spoil heaps are the terraced slopes, so typical of the former mining landscape. The main street and the elongated town square follow the valley of the Jáchymovský Stream, while all the side streets and alleys on the steep slopes on either side reveal that the town still depends on kilometres of retaining walls and dozens of staircases (Fig. 25).

Fig. 24. New drainage adit

Fig. 24. New drainage adit

Fig. 25. Jáchymov levels

Fig. 25. Jáchymov levels

On one of the hills above the spa centre stands the Chapel of Saint Barbara, built in 1777 and also dedicated to the patron saint of all miners (Fig. 26). This chapel is quite unusual, however, as it has two small towers on its roof, symbolising the unity of the local miners and metallurgists in Jáchymov, who together initiated its construction. Another interesting fact is that in 1917 the chapel was moved to the hill above the spa park, including its interior furnishings, because it originally stood in the town centre on the site of today’s Hotel Astoria, where it had begun to obstruct the developing spa facilities.

Fig. 26. St Barbora Chapel

Fig. 26. St Barbora Chapel

The Radon Trail

In the April issue of VTEI [1], we became acquainted with two routes in Jáchymov – the Valley of the Mills and the Mill Trail. Now, let us take a walk along another route, which also passes through Jáchymov and the surrounding forests full of curiosities (Fig. 27). In addition to offering charming views of the Jáchymov levels already mentioned, it has educational value. This is the Radon Trail, established in Jáchymov in 2011 in cooperation with the town authorities. Two years ago, the trail was replaced with a newer, more popularised version. Its primary purpose is to serve as an educational tool, raising awareness of radon in the local environment, methods of measurement, potential risks associated with exposure, and possibilities for prevention.

Fig. 27. One of the local natural phenomena

Fig. 27. One of the local natural phenomena

That the world’s first radon trail was established in Jáchymov is more than logical. The reason lies both in the local geological conditions – the bedrock, crisscrossed with historic adits, allows radon to penetrate buildings – and in the use of construction materials from mining waste, which contain radioactive elements and emit gamma radiation. The town has actively addressed this long-standing issue, and an obvious partner and provider of expert support is the State Office for Nuclear Safety, which continuously monitors the local radiation situation. Another

partner in establishing the trail was the Ministry of Industry and Trade. The Radon Trail has a total of ten stops with information panels, from which visitors gradually learn about radioactivity, natural sources of ionising radiation and radon, as well as its effects on human health, the ways radon penetrates buildings, and more. Perhaps the most surprising finding along the trail is that the most significant source of radiation exposure for humans comes from nature itself – specifically, the radioactive gas radon, which is present all around us. The final two panels focus directly on the spa and its treatments. The trail returns to them along a fresh forest path (Fig. 28). Were it not for the still-legible inscription on an old bench made of planks – “they can close you up, but they must let you out” – it would be hard to believe, on this sunlit path, just how turbulent the history of Svornost Mine, and indeed of Jáchymov as a whole, has been.

Fig. 28. Radon Trail

Fig. 28. Radon Trail

Jáchymov lives

To end on a more optimistic note, let us return to Jáchymov’s traditional balneology, the many satisfied patients from all over the world, and their highly effective treatment with unique radon baths, originally known as radioactive emanations. Visitors to Jáchymov – this spa town nestled in the forests of the Ore Mountains – are always eager to return, some even as many as twenty times in succession, to undergo treatment and recharge their vital energy. Thanks to them, Jáchymov is now awakening to a new era. Historic buildings are being restored, new shops and guesthouses are opening to accommodate visitors, and the spa houses offer a rich social and cultural programme – including lectures, guided excursions, and concerts of popular, dance, and classical music, often featuring promising young artists (Fig. 29).

Fig. 29. Pianist and composer Marek Kovářík (Běhounek Spa House, May 2025)

Fig. 29. Pianist and composer Marek Kovářík (Běhounek Spa House, May 2025)

Photos on pp. 52–59: Z. Řehořová

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to the management of Svornost Mine for the opportunity to descend to the twelfth level, 500 metres underground, and for the guided tour with expert commentary. My thanks also go to the Head Physician of the spa, MUDr. Jindřich Maršík, MBA, Prof. Ing. Tomáš Čechák, CSc., and the other speakers at the conference The legacy of Marie Curie in Jáchymov Spa and the 100th anniversary of her visit for their highly engaging presentations. I am deeply grateful that, during the conference, I had the chance to meet, for the last time, the Chair of the State Office for Nuclear Safety, Ing. Dana Drábová, Ph.D., Dr.h.c.,

who sadly passed away while this article was being prepared.

An informative article that is not subject to peer review.