ABSTRACT

Thermometry is a non-invasive technique suitable for detecting hidden mineral water springs. Its applicability was evaluated in two contrasting hydrogeological settings: Mariánské Lázně, characterized by cold, CO₂-rich mineral springs, and Karlovy Vary, dominated by thermal springs.

In Mariánské Lázně, the objective was to identify previously undocumented springs. Ground thermometry with a thermal infrared (TIR) camera proved highly effective. The survey was supplemented by measurements of free dissolved CO₂ (Härtl tube), temperature, electrical conductivity, and pH. A total of 131 thermal anomalies were recorded along 20 km of watercourses, 14 of which were confirmed as new mineral springs. The actual number of springs is likely higher, as CO₂ analyses are limited in springs strongly diluted by surface water.

In Karlovy Vary, the aim was to localize and quantify wild thermal springs (up to 73.4 °C) within the bed of the Teplá river, which influence the equilibrium of the entire spring system. TIR imaging was ineffective due to rapid dilution by river water. Therefore, point temperature measurements were performed in a regular grid over a 1,300 m² area of the riverbed. This approach revealed 14 untapped so-called wild thermal springs. In parallel with water temperature measurements, electrical conductivity was also continuously recorded, and at the end of the mapping a summary discharge balance of the springs was attempted, unsuccessfully, using a FlowTracker device based on water flow measurements in the Teplá. Ultimately, the total yield of the wild springs in the study area, that is, in the vicinity of the Vřídlo springs, was estimated at 2–3 l/s. This estimate is based on long-term changes in pressure conditions within the Vřídlo structural system.

The results of both thermometric surveys demonstrate that, when an appropriate workflow is applied, thermometry represents a highly versatile and effective method for the qualitative assessment of mineral water discharges. However, for successful application, the methodology must always be adapted to the specific hydrogeological and hydrological conditions of the site. The results of both partial surveys provided information on the distribution of mineral springs and will serve as a basis for defining the protection of spring structures.

INTRODUCTION

In hydrogeological practice, thermometry is most commonly used to identify concealed inflows of groundwater into surface waters. It represents an alternative to simple discharge measurements in a watercourse, where differences in flow are assumed to be caused by groundwater inflow. Thermometry is based on the premise that groundwater usually exhibits a more stable temperature throughout the year compared with the more variable temperatures of surface water [1]. The temperature of groundwater in the near-surface zone of the geological environment approaches the mean annual air temperature and increases with depth below ground as a result of the geothermal gradient. This thermal contrast creates anomalies in watercourses or receiving waters at locations where groundwater emerges [2], which can be detected using probe thermometers, cameras recording in the infrared thermal spectrum (TIR), or standard conductometers with a temperature sensor, both through in situ measurements and remote sensing [3]. The thermal contrast can be understood as a natural non-conservative tracer. Its advantage lies primarily in its ubiquity, natural occurrence, non-invasive nature, and ease of detection, which enables rapid mapping [4]. Unlike conservative tracers, whose concentrations are directly related to mixing ratios [5], the quantitative interpretation of thermal anomalies in terms of discharge estimation is indirect and complex [6]. The measured temperature signal is influenced by the temperature of groundwater, surface water, the degree of mixing with surface water, and heat exchange with the atmosphere, which depends, inter alia, on the thermal capacity of water. For these reasons, thermometry is considered a qualitative, or in some cases semi-quantitative, method.

The effectiveness of detecting a thermal signal is directly related to the magnitude of the temperature difference (∆T). Under conditions in the Czech Republic, thermometric surveys are most effective in winter, when relatively warm groundwater contrasts with cold water in streams or receiving waters. However, diurnal temperature fluctuations are also important. Surveys conducted at night or under complete cloud cover minimise disturbing effects [3]. Detection is further influenced by seasonal variability in stream discharge: at higher flows, the detection threshold increases and sensitivity decreases. In general, better results can be achieved under calm conditions and during periods without recent precipitation, which tends to homogenise the temperature of the water column. Heat exchange is influenced by conduction, convection, and radiation, as well as by transport processes, predominantly advection, whereby heat is transported with the movement of groundwater and, respectively, surface water [6]. The second main transport mechanism is thermal dispersion, which arises as a result of differing flow velocities [7]. Although it is sometimes simplified or neglected in models, particularly at low flow velocities, dispersion can be important for the accurate interpretation of heat transport processes [7]. The combination of these processes determines the size, shape, and intensity of the thermal signal. In qualitative assessments, it is assumed that the intensity and size of a thermal signal reflect the discharge or temperature of a spring (a larger or more pronounced anomaly approximately corresponds to higher discharge or a higher inflow temperature) [6]. The shape of the thermal signal is influenced by flow direction and mixing dynamics [8]. In quantitative applications, the main difficulty is the aforementioned non-conservative nature of the “tracer”. It is necessary to take into account the thickness of the water column above the discharge point, the degree of mixing, the velocity of surface water flow, and the influence of atmospheric conditions. There is no universal calibration for quantification, and each site must therefore be assessed individually [9, 10].

Experience with the use of thermometry for locating concealed springs is extensive both internationally and within the Czech context. However, in the field of natural medicinal resources, this method has not yet become part of routine practice, and experience with its application remains limited. Thermometry was used, for example, in the mapping of the tectonic structure of western Bohemia, including the wider surroundings of Mariánské Lázně. This work was carried out between 1984 and 1988, and areas such as the Pott valley in Mariánské Lázně were surveyed using thermometric methods [11]. The results, however, were intended primarily to verify the hypothesis that abundant groundwater discharges are tectonically predisposed, while issues related to natural medicinal resources were largely not addressed, reportedly also due to the low sensitivity of the detectors available at that time. In Karlovy Vary, so-called commission inspections using thermometry were conducted in 1980 [12], but their purpose was not to quantify measurements; rather, they served as reconnaissance of the site in connection with ongoing remediation works. Measurement data from these inspections in Karlovy Vary are not available.

OBJECTIVES

The main objective of the thermometric survey in both Mariánské Lázně and Karlovy Vary (Fig. 1) was to identify previously unknown mineral water discharges. Knowledge of the spatial distribution of mineral springs is crucial for the appropriate design of both preventive and remedial protection measures, including those related to already recorded and exploited discharges. A partial objective was to describe the specific aspects of the application of thermometry in the exploration of mineral water outlets, with two contrasting sites deliberately surveyed in order to verify the applicability of the method across a broader range of conditions. The Mariánské Lázně area is spatially extensive and is characterised by discharges of cold mineral waters enriched with free dissolved (hereafter f. d.) CO₂, whereas the Karlovy Vary area is spatially limited and typical of thermal water discharges. Mariánské Lázně was selected because the search for cold mineral springs places higher demands on the applied technology, which ultimately results in a higher explanatory value of the outcomes obtained from testing thermometry in mineral spring detection. Sub-objectives were defined separately for each site.

Fig. 1. Areas studied with thermometric survey

Fig. 1. Areas studied with thermometric survey

Sub-objectives for the Mariánské Lázně site

The sub-objective was to use newly identified mineral water springs for sampling and, on this basis, to better understand spatial patterns in their composition. The current concept of the hydrochemical zonation of mineral waters is based solely on data from recorded springs [13]. The significance of identifying additional, less abundant, unrecorded mineral springs or seepages is also related to the requirement of the Slavkovský les Protected Landscape Area (PLA) to register and protect mineral water springs as a whole, regardless of whether or not they have designated protection zones. Without knowledge of their location and physical and chemical properties, it is not possible to ensure effective protection of discharging mineral waters. This is also closely linked to the question of the tectonic control of water chemistry and the spatial distribution of springs.

Sub-objectives for the Karlovy Vary site

The sub-objective of the thermometric measurements in Karlovy Vary was to verify whether the current natural and artificial sealing layers at the bottom of the Teplá river channel are sufficiently effective in preventing uncontrolled discharges of thermal water in the lowest parts of the valley. The quality of sealing has always played a crucial role in the trouble-free exploitation of the Vřídlo spring; therefore, the spring sedimentation forming the natural sealing layer had to be continuously supplemented with additional artificial sealing elements to prevent undesirable breakthroughs of thermal water [14]. However, the artificial sealing was never completed over the entire area of the Teplá river channel in the centre of the discharge zone. This area is thus still affected by numerous leakages of thermal water as well as spring gas directly into the surface recipient [15]. In the event of more significant damage to the sealing of the channel bottom in the vicinity of the Vřídlo spring, a decrease in the yield of nearby small springs occurs and degassing of the structural centre takes place. The results of the survey will serve as baseline material for the administrators of the local natural medicinal resources.

STUDY AREAS

Mariánské Lázně

In Mariánské Lázně and its surroundings, more than 100 mineral springs emerge, all of which are characterized by high CO₂ degassing, low temperatures ranging from approximately 7 to 12 °C, and relatively low yields from 0.01 to 1 l/s. The springs differ from one another primarily in their highly variable total dissolved solids (TDS), ranging from 0.2 to 12.0 g/l, as well as in their chemical composition [13, 16]. Based on chemical composition, four main groups of springs can be distinguished, with each group being formed under specific lithological conditions. The first group is associated with serpentinites, the second with amphibolites, the third probably with infiltrated fossil mineralization. The fourth is a so-called transitional group, in which the chemistry is influenced by combined lithology, too short a contact time with the bedrock, or by lithology that does not exhibit a clearly defined chemical signature [16]. These general findings concerning the spring system formed the basis for the design of an appropriate methodology for the thermometric survey.

Karlovy Vary

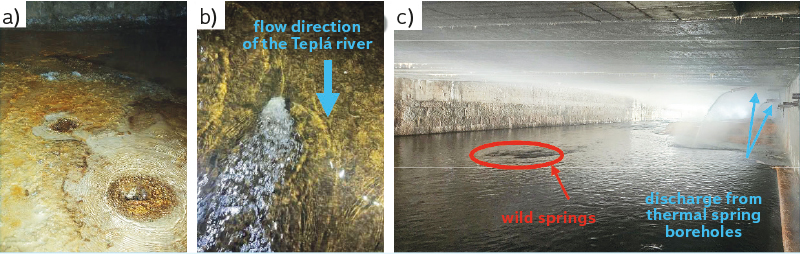

The discharges of the Karlovy Vary thermal waters, with a maximum temperature of 73.4 °C and a total dissolved solids of 6.4 g/l, together with emissions of spring gas, are confined to an approximately 1,700 m long and about 150 m wide discharge zone within granites. The total yield of the spring structure is approximately 33 l/s. From the perspective of the distribution of thermal water and spring gas yields, the centre of the discharge zone lies close to the historical position of the Vřídlo spring, which accounts for about 95 % of the yield of all Karlovy Vary springs. All thermal springs in Karlovy Vary are chemically identical, with the exception of the Hadí and Štěpánčin springs, which have lower mineralisation. Individual springs differ from one another only in temperature and CO₂ concentration [17]. The temperature of the springs is influenced primarily by the ascent velocity of the thermal water along favourable discontinuities towards the surface and, to a certain extent, also by the distance of the discharge point from the centre of the structure. A completely specific phenomenon within the discharge zone is the presence of carbonate spring sediments (aragonite shield) with a thickness of more than 10 m in places [14, 18]. In Karlovy Vary, untapped (“wild”) springs (Fig. 2) have been known for centuries and have always had a significant impact on the exploited springs. The causes of wild springs resulting from failures in the sealing of the riverbed are both natural (river erosion, changes in pressure within the structure, etc.) and anthropogenic (construction works, krenotechnical systems; facilities for the collection and distribution of thermal spring water to hotels, translator’s note, etc.) [19]. The regime of the Karlovy Vary springs is also influenced, for example, by tidal forces [20]. These general insights into the structure formed the basis for the design of an appropriate methodology for thermometric mapping of wild springs.

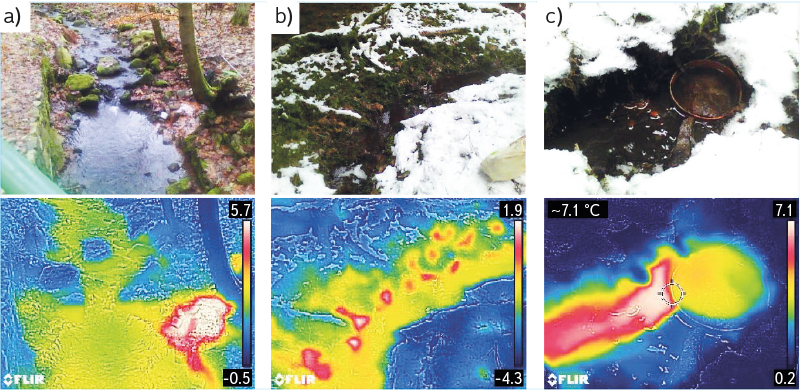

Fig. 2. Untapped ‘‘wild’’ springs; a) springs in the old basement of the Vřídlo, b) wild springs in the Teplá riverbed, c) general view under the bridge with visible untapped springs

METHODOLOGY

For publication purposes, a mineral water spring in the case of Mariánské Lázně is defined as one exhibiting a free CO₂ concentration > 1 g/l, i.e., a carbonated mineral spring, and in the case of Karlovy Vary as one with a temperature > 20 °C, i.e., a thermal spring. A temperature anomaly refers to any thermal irregularity detected by a thermal camera. A new or “wild” mineral water spring is defined as a thermal anomaly where an elevated free CO₂ concentration has been detected using the Härtl shaking apparatus (hereinafter referred to as the Härtl tube), or where the temperature is at least approximately 3 °C higher than the background water temperature.

Mariánské Lázně

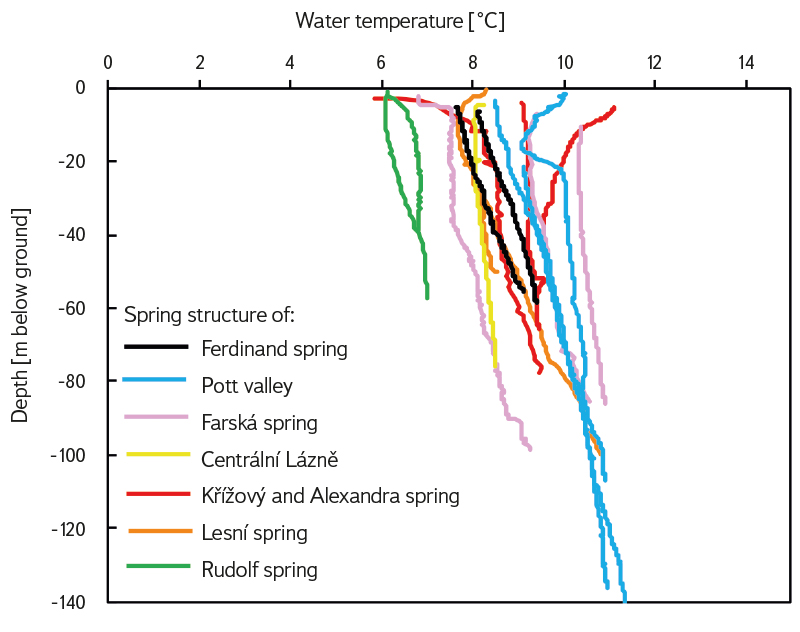

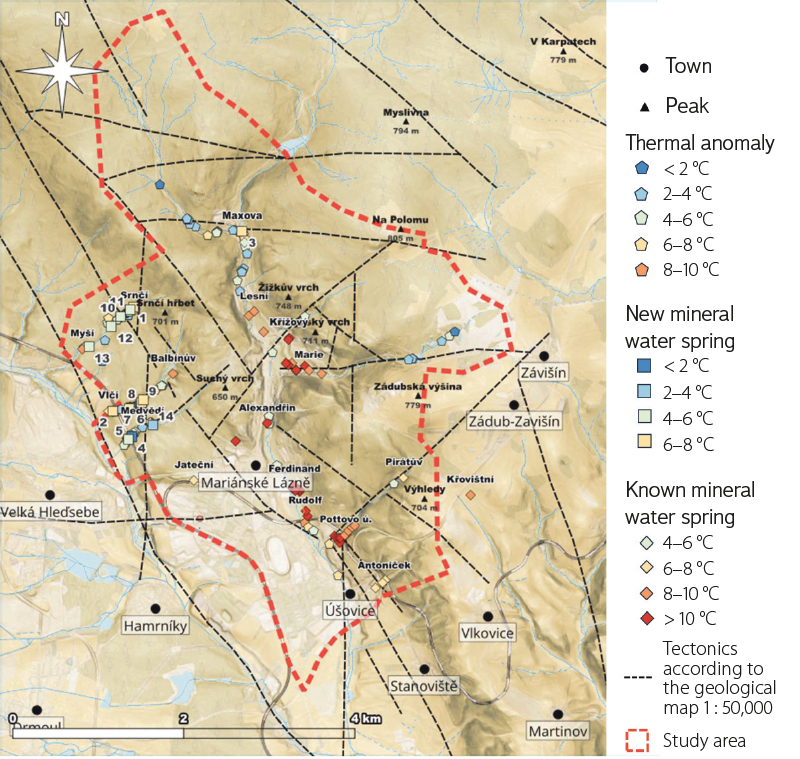

In the study area (Fig. 4), watercourses were first identified using the Basic Geographic Data Base of the Czech Republic (ZABAGED). The thermometric survey itself took place from January to March 2023, using a FLIR C5 TIR camera (USA), capable of measuring temperatures from -20 °C to +400 °C with a capture frequency of 8.7 Hz and a resolution of 240 × 320 pixels in its basic mode, i.e., with automatic calibration. The sequence of activities following the identification of a temperature anomaly of unknown character included: marking the site with a stake, photographic documentation, GPS positioning using a mobile phone, measurement of conductivity, temperature, and pH using a WTW Multi 340i device with a TetraCon 325 probe and a pH-Electrode SenTix 41, and finally, determination of flow rate and free dissolved CO₂ concentration using Härtl tube. Although all identified temperature anomalies were surveyed, sampling for chemical analysis was carried out only for those anomalies in which the presence of free dissolved CO₂ was detected using the Härtl tube, i.e., at new mineral water springs. The most significant new mineral water springs, in terms of flow rate and CO₂ content, were assigned not only an identification number but also names corresponding to nearby springs. For improved spatial accuracy, the temperature anomalies were geolocated in March–April 2023 using an RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) GPS station. Subsequently, an interpretation was carried out and the data were compared with the temperatures and electrical conductivities of previously recorded mineral springs, taking into account that the water temperature in exploited mineral water boreholes increases with depth by an average of 1.6 °C per 100 m (Fig. 3), and that some abstraction points have overflow, which further reduces interpretability. All new mineral water springs were monitored regularly until July 2024 to verify that they were not of a temporary character.

Fig. 3. Change in water temperature with depth in exploited mineral water boreholes in individual spring structures in Mariánské Lázně (adapted from [21])

Karlovy Vary

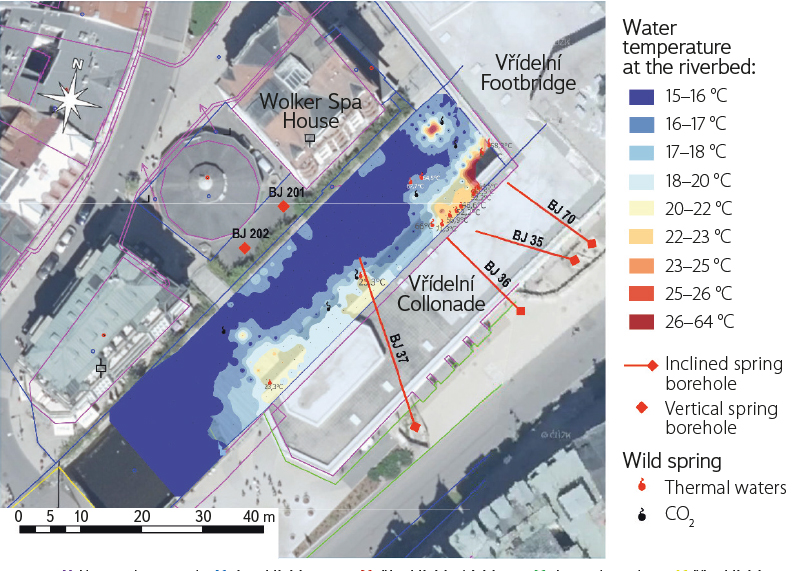

The methodology for locating the thermal spring sources was adapted to the smaller areal extent of the area, the higher temperature of the springs, and the higher dilution ratios, as the Teplá river carries approximately 1.5 m³/s with a water column of about 0.4 m, which precludes the use of a TIR camera. Point measurements were carried out using a conductometer with a temperature sensor arranged in a defined grid. For measuring temperature and electrical conductivity, a Greisinger (Germany) G 1410 instrument was used, allowing temperature measurements from −5.0 to 105.0 °C with an accuracy of ± 0.3 °C. The temperature sensor was encased in insulating foam to ensure that it measured only the temperature at the bottom of the Teplá riverbed. Thermal profiling was conducted over an area of approximately 1,300 m² on 11 September 2024. For profiling purposes, a regular grid was established from Janský most to Vřídelní lávka, i.e., in areas without additional artificial sealing. The spacing between measurement points was 5 m, or 2 m and 1 m in locations where thermal spring discharges were expected. At points with anomalously high temperatures, the exact location of the thermal spring was manually identified and recorded. Subsequent spatial evaluation was performed using the deterministic interpolation method IDW (Inverse Distance Weighting). This methodology was chosen with the understanding that a potential spring could be located even outside the measured points. Thermometry was complemented by flow measurements of the Teplá river, taken both upstream and downstream of the area of interest using a FlowTracker device. These measurements were intended to help balance the total discharge of the wild springs.

RESULTS

Mariánské Lázně

Using thermometry along 20 km of watercourses in the study area, 14 new mineral water springs were identified, while a total of 131 thermal anomalies were recorded (Fig. 4). The thermal anomalies most commonly exhibited an elliptical shape, elongated in the direction of surface water flow. In the case of the new mineral water discharges, it was often observed that the water emerged above the stream bed, overflowing the edges of the spring sediments (Fig. 5a). The new mineral water discharges were distributed unevenly across the area; except for one occurrence (P013A Chudá), their location was restricted to the western part of the area (Fig. 4). Thermal anomalies were also detected in the very centre of Mariánské Lázně, where an anomaly with a temperature of 5 °C and a conductivity of 1,725 µS/cm was measured at the bottom of the partially drained Labutí jezírko. However, the dissolved CO₂ content could not be measured using the Härtl tube, and therefore this trace was not classified as a new mineral water spring.

Fig. 4. Thermometric measurements in Mariánské Lázně

1 = P004/P069 Žabí, 2 = P011, 3 = P013A Chudá, 4 = P035, 5 = P037D Ježčí, 6 = P045A,

7 = P047 Mravenčí, 8 = P053 Šnečí, 9 = P054 Sýkorčí, 10 = P059B, 11 = P067A, 12 = P071, 13 = P073, 14 = P116 (Source: map: DMR 5G)

Thanks to thermometry carried out in freezing conditions, it was possible to detect thermal anomalies at absolute temperatures as low as 1.9 °C (Fig. 5b). Many of the new mineral water discharges were accompanied by iron coatings, emissions of gaseous CO₂, distinctive organoleptic properties, and resistance to freezing. All 14 new mineral water springs consistently exhibited a pH value below 7. For some thermal anomalies, the dissolved CO₂ content could not be measured due to significant dilution by surface water. For this reason, it cannot be excluded that the actual number of mineral water springs is higher. Although the entire discharge system is generally associated with the Mariánské Lázně fault zone, the influence of local tectonics on the spatial distribution of discharges could not be determined (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5. Thermal camera images; a) Lucčina kyselka, b) small springs in the river floodplain, c) Žabí kyselka springing outside the spring catchment

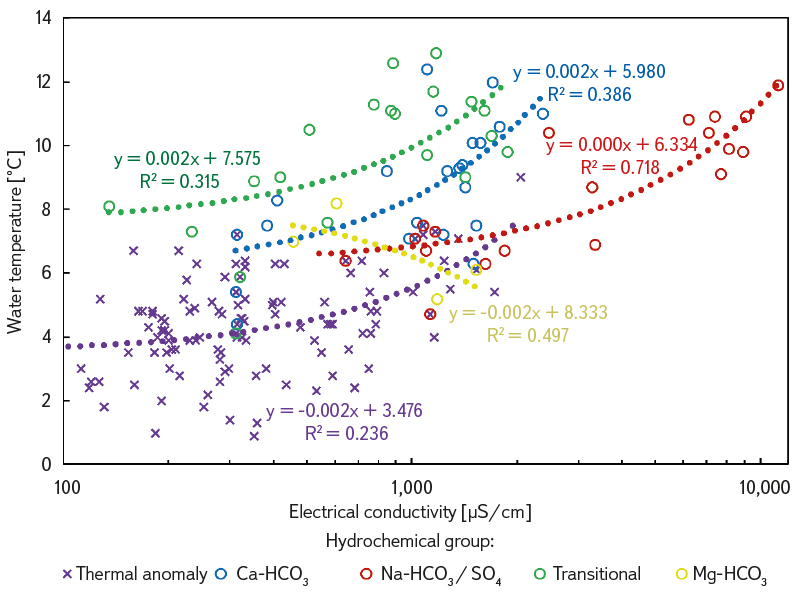

Supplementary conductivity measurements of the thermal anomalies revealed a poor correlation with temperature (Fig. 6). A slightly better correlation is observed when the dataset of new and existing mineral water discharges is divided into hydrochemical groups. In general, however, water temperature is not a suitable predictor for estimating conductivity. The highest coefficient of determination, R² = 0.718, was observed for the Na-HCO₃ / SO₄ group, while the other groups showed significantly lower determination coefficients (R² = 0.315 and 0.386). The only group showing a decreasing temperature with increasing conductivity was Mg-HCO₃ (R² = 0.497); however, this dataset is limited to only four discharges. It was found that higher spring discharge results in lower annual water temperature fluctuations.

Fig. 6. Relationship between seepage temperature and conductivity for temperature anomalies and all known seepages (new and existing) divided by hydrochemical groups in Mariánské Lázně

Beyond its original purpose, the TIR camera proved to be a suitable tool for verifying the status of mineral water discharge record. Fig. 5c shows that Žabí kyselka, a newly discovered and provisionally recorded spring, discharges outside the collection system. Repeated monitoring of the new mineral water discharges revealed significant seasonal variations in both temperature and flow rate, with the lowest temperatures occurring in winter and the highest in summer. In contrast, conductivity and pH values remain almost stable. Out of the 14 new mineral water springs, 11 were sampled for chemical analysis, and the results will be used for the future revision of protection zones within the Slavkovský les PLA.

Karlovy Vary

The thermometric survey, supplemented by conductometry of the Teplá riverbed around the Vřídelní Collonade, revealed the presence of 14 wild discharges of thermal mineral water over an area of 1,300 m². In terms of spatial distribution, the wild discharges are concentrated along the right bank of the Teplá riverbed, with the highest density at the level of the Wolker Spa House. Only four discharges were identified in the centre of the flow or outside the Wolker Spa House section. The fact that wild discharges are predominantly found along the right bank of the Teplá opposite the Wolker Spa House aligns with the historical and current intake points of the Vřídlo (BJ 35–37, 70), which have always been located on the right bank. The highest concentration of wild mineral springs is located near the bases of the inclined spring boreholes BJ 35, BJ 36, and BJ 70. A wild mineral water spring was also found above the fourth spring borehole, BJ 37, although its temperature reaches only 23.3 °C. Even though it was not possible to completely prevent contact between surface water and the temperature/conductivity probe, the highest recorded temperature of a wild spring was 71.3 °C, and the highest measured conductivity was 7,470 µS/cm – values almost identical to those of the Vřídlo spring. Beyond the original scope, six main sites of gaseous CO₂ escape through the Teplá’s water column were visually identified.

Fig. 7. Thermometric measurements in Karlovy Vary

Due to the well-known long-term variations in the discharge of the structure and pressure changes at the regulating wells, it has been estimated that wild discharges currently flow into the Teplá riverbed with a total flow rate of approximately 2 to 3 l/s, including an unknown amount of gaseous CO₂. The total flow of the wild springs was also tentatively assessed using a FlowTracker device, but due to its ± 10 % accuracy, the measurements did not yield the expected results.

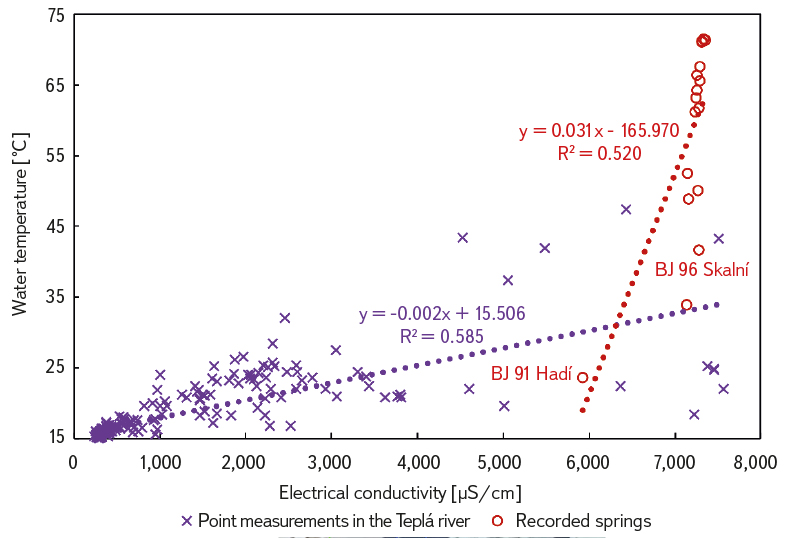

Analysis of the data revealed a correlation between water conductivity in the defined network and temperature, with a coefficient of determination R² = 0.585. Although the coefficient is very similar for the already recorded springs (R² = 0.520), the distribution of values is entirely different. The Hadí spring is the only recorded spring with a distinctly different conductivity. It is the most distant discharge from the centre of the structure, has the highest concentration of dissolved CO₂, and is also the coldest (Fig. 8). Therefore, it can be excluded from the dataset. By analogy with wild mineral water springs, it can be concluded that water temperature is not a reliable precursor for determining conductivity, because if dilution by the Teplá is prevented, the conductivity for all new wild springs would be the same, i.e., ± 7,300 µS/cm, while the water temperature would vary depending on the discharge rate of the thermal water.

Fig. 8. Relationship between point measurements of water temperature at the bottom of the Teplá riverbed and recorded springs on conductivity

DISCUSSION

The methodology for the thermometric survey must reflect the required nature of the survey results. The data collection typology in Mariánské Lázně was adapted to the considerable spatial extent of the area, whereas in Karlovy Vary it was adjusted to the high temperature gradient between surface and thermal waters. Both methodologies proved to be highly effective and each led to the successful identification of mineral water springs.

The results of the survey have practical implications at both sites. In Mariánské Lázně, they are particularly relevant for the Nature Conservation Agency of the Slavkovský les PLA, which seeks to adopt an objective approach to protecting even the less significant mineral water discharge structures. In Karlovy Vary, the findings are important for the administrators of natural medicinal resources (Administration of Natural Medicinal Resources and Colonnades), who are implementing the results in a sealing works project near the Vřídelní Colonnade. The high total discharge of the wild springs into the Teplá river may be linked to the recent reconstruction of part of the Vřídelní Colonnade between 2019 and 2023, which, due to pressure changes, reactivated the wild springs.

Although thermometric measurements, whether using a TIR camera or a temperature probe, proved to be a highly effective tool for locating water discharges and measuring the CO₂ content of mineral water springs, it should be noted that it was not possible to perform Härtl tube measurements on all the identified thermal anomalies in Mariánské Lázně due to the impossibility of isolating surrounding watercourses. Therefore, the total number of new mineral water springs within the set of 131 thermal anomalies may be higher, which is why all thermal anomalies are included in the study results. The discrepancy between the number of detected thermal anomalies and the number of confirmed mineral springs is primarily due to the fact that discharges of ordinary water are far more frequent, even under the conditions in Mariánské Lázně. Even though mineral water discharges are generally warmer during frosty conditions, the methodology was followed consistently: all anomalies exceeding the background temperature by approximately 3 °C were marked. Discharges that were not detected may have been diluted by surface water, which complicates their identification. In Karlovy Vary, a limiting factor was the measurement grid with intervals of 1 to 5 m, which undoubtedly led to some discharges not being identified because they fell between measurement points. Continuous temperature measurement was not a viable solution, as the sensor’s response time was insufficiently fast. At the same time, despite efforts to minimise other interfering factors, it should be emphasised that in Mariánské Lázně it was not possible to maintain completely consistent meteorological conditions, such as daily temperature cycles, thaws, etc., throughout the entire duration of the thermometric survey.

Comparison of the new measurement results with data from the 1980s, both in Mariánské Lázně and Karlovy Vary, shows that modern technologies can significantly increase the success of surveys. While the authors of the study conducted between 1984 and 1988 in the wider Mariánské Lázně area reached rather inconclusive results, springs were successfully located in the survey carried out in 2023–2024. The earlier thermometric survey was conducted without the use of a TIR camera, which would have sped up, improved the accuracy of, and reduced the cost of data collection. The 1980 survey in Karlovy Vary was more of a reconnaissance in nature, so the authors’ conclusions were purely qualitative, for example, leaks of thermal water were found along the casing perimeters of the wells in the riverbed.

Quantification of discharge could not be achieved from either the thermometric data or the supplementary conductometric data. It should be noted that in Mariánské Lázně the mineral water springs exhibit highly variable conductivity but nearly uniform temperature, whereas in Karlovy Vary the springs have almost identical conductivity but differing temperatures. Furthermore, while in Karlovy Vary only the temperature of the mineral water increases with depth of abstraction, in Mariánské Lázně it is primarily the conductivity that increases, as confirmed, for example, in the Ferdinand spring structure [16]. The fact that the springs in Mariánské Lázně have similar temperatures could facilitate the quantification of discharge; however, this would require ideal conditions, as mentioned in the introduction. Subsequently, in the case of parallel conductivity measurements, it would even be possible to calculate the conductivity of a spring using a mixing equation. Within the study, the relationship between conductivity and temperature was tested, but the results are inconclusive. Correlating conservative conductivity with non-conservative temperature presents considerable challenges, even though, in the context of this study, the two parameters are not independent, as evidenced by the data from the recorded springs (Fig. 6). In Karlovy Vary, the unknown temperature of the spring as it emerges into the channel is additionally problematic. This is caused by the varying rate of thermal water discharge to the surface, partly by the distance from the centre of the discharge zone, and consequently the depth of capture. For this reason, in the case of recorded smaller springs (e.g., Skalní, Mlýnský, Sadový), the temperature of the springs has previously increased, as a preferential pathway was created, shortening the residence time within the rock matrix [17].

CONCLUSION

The research focused on the use of thermometry as an effective tool for locating mineral water discharges. However, this method cannot be regarded as self-sufficient for the identification of mineral springs and should be complemented, for example, by measurements of free CO₂ or electrical conductivity. Thermometry was applied at two contrasting sites: Mariánské Lázně, characterised by cold springs, and Karlovy Vary, with thermal springs. In Mariánské Lázně, the use of a TIR camera enabled the identification of 14 new, low-yield mineral water discharges. It can be concluded that thermometry alone is not sufficient to unambiguously determine the presence of emerging non-thermal, gas-rich springs (< 20 °C). On the other hand, when combined with measurements using a Härtl tube, a conductometer, and a pH meter, it represents the most effective and also the least costly method for locating even low-yield discharges of gas-rich mineral waters. It should be noted that thermometry is naturally applicable also to the detection of non-mineral groundwater outflows. The results will be submitted to the administration of the Slavkovský les PLA for the purposes of registration and improved protection of mineral waters in the area.

For the survey in the channel of the Teplá in Karlovy Vary, a point-based measurement method using a conductometer with an integrated temperature sensor arranged in a regular grid was selected. The thermometric analysis demonstrated the presence of 14 wild discharges of thermal water in the channel of the Teplá over an area of 1,300 m², reaching temperatures of up to 71.3 °C and conductivities of up to 7,470 µS/cm. The total yield of the wild discharges in the area of interest was estimated at approximately 2–3 l/s. The thermometric results constitute a key basis for the planned remediation works in the Teplá riverbed. Repeating the measurements after the remediation has been carried out can be considered desirable in order to verify its effectiveness.

Thermometry is suitable for rapid mapping of interaction zones between groundwater and surface water, particularly due to its non-invasive nature. The effectiveness of the method depends on optimal timing of the measurements (diurnal and seasonal periodicity) and on the magnitude of the temperature difference (∆T) between groundwater and surface water. Quantitative interpretation of thermal anomalies in terms of discharge is complicated, as temperature is a non-conservative tracer. Quantification therefore requires calibration for the specific site and conditions. The research confirmed that, despite the general limitations regarding quantification, thermometry is well suited for the qualitative assessment of concealed springs. Application in the field of mineral waters, as demonstrated by both parts of the study, is highly effective, but requires careful consideration of local conditions when selecting the appropriate methodology. In the future, further increases can be expected in the sensitivity and refresh rate of TIR sensors, their affordability, and the availability of additional sensors (including hyperspectral sensors). Simultaneously, improvements are anticipated in atmospheric correction algorithms, emissivity measurements, and the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning, as well as in the fusion of these data with remote sensing data, particularly from drones. This will lead to simplification of spatio-temporal monitoring and enable broader application in hydrology and hydrogeology.

Acknowledgement

The research carried out within the project Spa Research Centre is funded from the Just Transition Fund (JTF) through project No. CZ.10. 01. 01/00/22_001/0000261.

The Czech version of this article was peer-reviewed, the English version was translated from the Czech original by Environmental Translation Ltd.