ABSTRACT

Protected areas of natural water accumulation have been long monitored and protected. So far, little attention has been paid to the catchment area which will be the future source of water for these water reservoirs from the point of view of influencing their quality. This article focuses on certain diffuse (non-point) processes that may lead to pollution and thus to limited use of accumulated water. It describes the methodology for identifying critical points in the vicinity of the future reservoir, where an excessive amount of sediment loads will enter the aquatic environment during torrential rainfall events. This will lead to sedimentation of the reservoir as well as to the input of dissolved pollutants. The methodology was applied to all 61 selected sites; the results are clearly presented in Tab. 1 and further discussed. As another non-point aspect, the representation of so-called Nitrate Vulnerable Zones within the reservoir catchment areas is evaluated. Although these areas are assessed in terms of excessive nitrate levels in water, other undesirable compounds used in agriculture may also occur there. As a third aspect, the article describes the status of the land consolidation process in the monitored catchments and discusses their contribution to catchment protection. In conclusion, it is stated that it would be necessary to enshrine into legislation the protection of LAPV catchments, especially for those reservoirs intended for drinking water supply.

INTRODUCTION

When assessing the purposefulness and efficiency of constructing a new reservoir, many parameters are important on the one hand – those that can be considered basic, technical, and can be clearly described and quantified. These include the type of reservoir, its capacity and inundated area, hydrological conditions, and so on.

On the other hand, there are numerous parameters that can be described as socio-economic. These include, for example, the attitudes of local people who will be affected by the construction, and the interests of various specialists, each of whom has defined different objectives they wish to achieve through the construction (or non-construction) of the reservoir. Anyone seeking to emphasise their own position and goals selects arguments that support them and downplays or ignores those that do not serve their purposes.

The Water Centre I project focused on the study of 61 sites from the 2020 Master Plan of Areas Protected for Surface Water Accumulation [1]. This selection took into account hydrological conditions, that is, areas that will need to be addressed as a priority in terms of water supply [2].

It is important to note that considerations regarding a future reservoir do not affect only the areas impacted by the dam construction itself and the area of the future floodplain. The reservoir brings problems as well as social and economic impacts both downstream and upstream of the affected watercourse: it improves overall conditions in the catchment (and the wider area) below the reservoir; however, it creates pressure on land-use possibilities above it. This aspect has so far received insufficient attention in the case of the protected areas of natural water accumulation (hereafter LAPVs) – most protective measures relate only to the area of the future dam and the anticipated floodplain. Within this scope, they were also adopted and recorded as a Territorial Reserve [3] in the Spatial Development Principles (hereafter SDP) of the regions. Fig. 1 shows the area of Terezín LAPV from the SDP of the South Moravian Region [4]. If requirements regarding land management and use in the catchment above the future reservoir are mentioned, they are general, non-specific, and their impacts on the lives of affected residents, on infrastructure, agriculture, and local businesses are not monitored. Meanwhile, the protection of the relevant catchment should be a permanent part of LAPV protection, and for sites of type A (drinking water) it should focus particularly on safeguarding water quality.

Fig. 1. Example of spatial development principles of the South Moravian Region [4]: LAPV Terezín – blue hatching

Fig. 1. Example of spatial development principles of the South Moravian Region [4]: LAPV Terezín – blue hatching

Therefore, in the project we focus primarily on identifying, describing, and listing the various aspects and impacts of the proposed construction of hydraulic structures on individuals and entire communities, as well as on different types of economic activity in the affected area. For this article, we have selected three phenomena that are related to the natural configuration of the landscape and its spatial use and transformation. The aim of this analysis is to compile the basis for comparing the proposed reservoirs in terms of individual aspects and their combinations, considering both the advantages and the issues that their construction may cause.

METHODOLOGY

In the first step, a spatial analysis was carried out for the relevant LAPV catchments or sub-catchments for each site. For these areas, the overlap with designated vulnerable zones and with areas under additional protection of hydrological importance was displayed, together with a list of affected water bodies, their current status, and the measures expected for them under the sub-basin plans. The source of some of this information was the relevant sub-basin plans [5–13].

Within the cadastral areas of municipalities belonging to the catchments of the individual sites, the status of the preparation and implementation of comprehensive land consolidation (hereinafter CLC) is monitored.

All the information obtained and processed for each site is stored in a database maintained in Excel and is used in other project outputs.

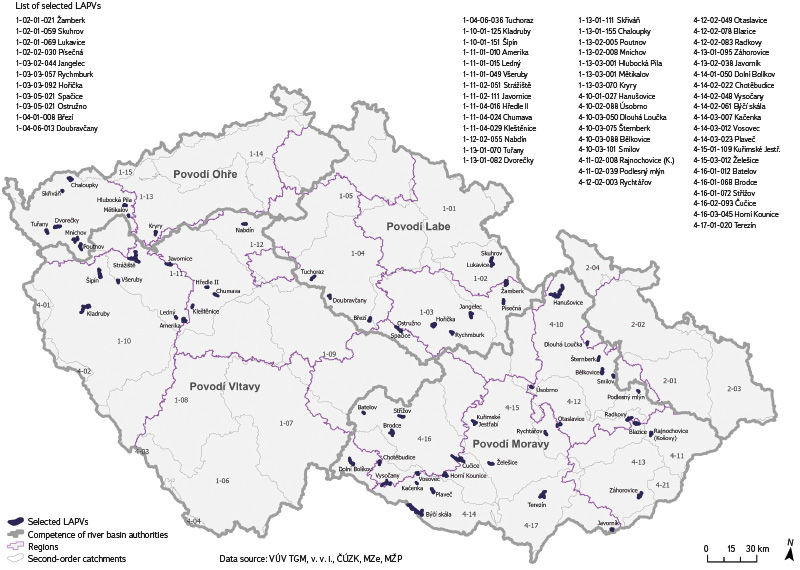

A total of 61 LAPV sites selected for the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic project No. SS02030027 Water Systems and Water Management in the Czech Republic under Climate Change Conditions (Water Centre), guaranteed by the Ministry of the Environment, were included in the analysis. The sites are clearly shown in the following map (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Location of protected areas of natural water accumulation selected for the project

Modified critical points

The main part of the analysis focused on assessing the immediate surroundings of future water bodies in terms of the risk of runoff erosion during torrential rainfall. The method of critical points was used, based on a morphometric and hydrological analysis of the digital terrain model (DTM) in ESRI ArcGIS for Desktop, or the more recent ArcGIS Pro [14]. Beside the ESRI environment, there are also other freely available software tools that enable similar DTM analyses. A significant example is SAGA GIS (System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses), which, in addition to DTM analysis, is also used for modelling surface runoff and erosion–sedimentation processes [15]. Another commonly used robust platform is GRASS GIS (Geographic Resources Analysis Support System), which also offers a range of advanced tools for DTM analyses and surface runoff simulations [16]. Based on the results of a case study [17], it can be stated that both open-source tools are becoming increasingly robust platforms for morphometric and hydrological DTM or digital surface model (DSM) analyses, whether considering the relatively simple determination of flow direction and flow accumulation or more sophisticated analyses.

Critical points are identified at locations where the flow path lines of concentrated runoff, generated on the basis of a DTM, enter the built-up areas of municipalities. The modified procedure replaces the settlement boundary with a line of inundation of the water reservoir. Given the nature of flash floods (for which the methodology is designed) and their predominantly local impacts, only critical points with a contributing area not exceeding 10 km² are considered. For each contributing area, the physical-geographical characteristics are calculated:

Pp,r – Relative size (with respect to the maximum of 10 km²) [-]

Ip – Average slope [%]

ORP – Proportion of arable land [%]

CNII – CNII value [-]

Hm,r – Relative value of the one-day precipitation total with a 100-year

return period [-]

The combination of physical-geographical conditions, land-use types, regional differences in land cover, and the potential occurrence of extreme precipitation (in relation to synoptic conditions) for specific contributing areas is expressed by the indicator of critical conditions for the emergence of adverse effects of flash-flood events F [-]. It is proposed in the form supplemented with the weights of the relevant variables.

where:

a is the weight vector [a1 = 1.48876; a2 = 3.09204; a3 = 0.467171]

Four criteria are used in the final selection of critical points (CPs). These differ for contributing areas of a predominantly agricultural character with more than 40 % arable land (referred to as variant A) and for areas where the proportion of arable land is below 40 % (variant B). Thus, the delineation also includes areas that are not primarily agricultural in character, but where investigations carried out in model catchments have nevertheless recorded damage caused by the transport of debris.

Variant A – combined criteria apply:

K1 size of the contributing area 0.3–10.0 km²

K2 average slope of the contributing area ≥ 3.5 %

K3 proportion of arable land in the catchment ≥ 40 %

K4 F – indicator of critical conditions ≥ 1.85

Variant B – combined criteria apply:

K1 size of the contributing area 1.0–10.0 km²

K2 average slope of the contributing area ≥ 5 %

K3 proportion of arable land in the catchment < 40 %

K4 F – indicator of critical conditions ≥ 1.85

The main output of the CP identification process is a spatial location of the selected CPs (Fig. 3) and a table of LAPV with the selected CPs. For each selected CP, the designation and the values of the area (km²), proportion of arable land (%), and average slope of the contributing area (%) are provided. The identification of CPs is the first step toward determining measures in the catchment aimed at mitigating or eliminating potential infilling of the reservoir area with sediment transported during intense rainfall events.

Fig. 3. Location of identified modified critical points for Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation

The basic data sources for the CP analysis were the datasets of the Digital Terrain Model of the Czech Republic, fourth generation (DMR 4G) [18] and fifth generation (DMR 5G) [19]. These are point clouds from airborne laser scanning of the Earth’s surface. Irregular triangular networks (TINs) were created from the point layers and subsequently a raster digital terrain model (DTM) with a resolution of 5 m. The DTM was subsequently modified using the so-called Fig. 3. Location of identified modified critical points for Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation “burning” method [20, 21] for features that may not be captured in the original DTM but can have a crucial influence on the direction and accumulation of surface runoff, and thus on the description of the real character of its formation and, ultimately, on the correct delineation of the contributing areas of the CPs. Specifically, layers from the planimetric section of the ZABAGED® database were used – watercourses, culverts, and bridges.

Vulnerable zones

Erosion wash-off in the reservoir catchment not only carries the risk of sedimentation in the reservoir but also the introduction of pollutants, particularly from diffuse sources of contamination, thereby causing undesirable deterioration of water quality in the reservoir. In the Master Plan of Areas Protected for Surface Water Accumulation [1], the sites are divided according to their importance into two categories:

- Category A comprises areas whose water-management importance lies primarily in their ability to create or supplement sources for drinking water supply, and possibly to fulfil other functions as well.

- Category B comprises areas that, due to their location and characteristics, are suitable for accumulation for the purposes of flood protection, meeting water abstraction demands, and enhancing flows (ensuring ecological flows in watercourses).

The factors threatening water quality in reservoirs include the input of pollution from agricultural sources. In view of these considerations, and in connection with the potential use of some LAPV as sources of drinking water, the percentage of vulnerable zones in the catchment – or in the sub-catchment of the protected LAPV – and the determined vulnerability of the inundated LAPV areas were included as an additional criterion.

The identification of vulnerable zones is based on the Nitrates Directive [22], which aims to reduce water pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources and to prevent further such pollution.

In the Czech Republic, the Nitrates Directive is transposed by Section 33

of Act No. 254/2001 Coll., on Waters [23], and defines vulnerable zones as sites where surface water and groundwater – particularly those used or intended as sources of drinking water – have nitrate concentrations exceeding 50 mg/l or may reach this value, or where surface waters are experiencing, or may experience, undesirable deterioration of water quality due to high nitrate concentrations from agricultural sources.

Vulnerable zones are established by government regulation. At the start of the project, Government Regulation No. 277/2020 Coll., on the designation of vulnerable zones and the action programme, was in force [24]. During the project, the fifth revision of vulnerable zones was carried out, and measures of the sixth action programme were established [25]. The revision was promulgated by Government Regulation No. 193/2024 Coll., effective from 1 July 2024 [26]. Vulnerable zones are delineated by

cadastral units of the Czech Republic [27]. For the purposes of the project, a dataset containing the list of cadastral units designated as vulnerable zones as of 1 July 2020 was used [28]. As an example, Fig. 4 shows the intersection with the declared vulnerable zones for the catchment above Terezín LAPV.

Fig. 4. Intersection with declared vulnerable areas for the catchment area upstream of Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation

Fig. 4. Intersection with declared vulnerable areas for the catchment area upstream of Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation

The Czech Republic issues a joint action programme for all designated vulnerable zones.

The method of maintaining records on the status of surface and groundwater is established by Decree No. 252/2013 Coll., on the scope of data in records of the status of surface and groundwater and on the manner of processing, storing, and transmitting these data to public administration information systems [29].

Comprehensive land consolidation

Land consolidation is one form of landscape planning and should ensure the use and protection of the landscape through biotechnical, organisational, and legal measures. It establishes the definitive form of landscape-shaping measures, with partial objectives including, for example, the simplification of land records or allocation procedures. Comprehensive land consolidations (CLC) address not only ownership rights of the lands involved but also include erosion control and water-management measures, the design of road networks, and measures to improve nature conservation and ecological stability of the landscape. They are usually carried out for entire cadastral areas (in contrast to uniform land consolidation – ULC, which typically takes place on smaller areas and among fewer landowners) [30].

Given that CLCs also include erosion control and water-management measures, the construction of a new reservoir may alter their function. Therefore, not only all cadastral areas affected by the potential inundation were considered, but it was also important to focus on cadastral areas within the catchment influenced by the reservoir, as its construction will also change runoff conditions in the surrounding smaller catchments. By overlaying the layer of cadastral maps with the areas of affected catchments in GIS, the affected cadastral areas were identified, and the status of CLCs in each cadastral area was checked on the Land Office portal [31]. An example of the method for Terezín LAPV is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Status of comprehensive land consolidation in the catchment of Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation

Fig. 5. Status of comprehensive land consolidation in the catchment of Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation

RESULTS

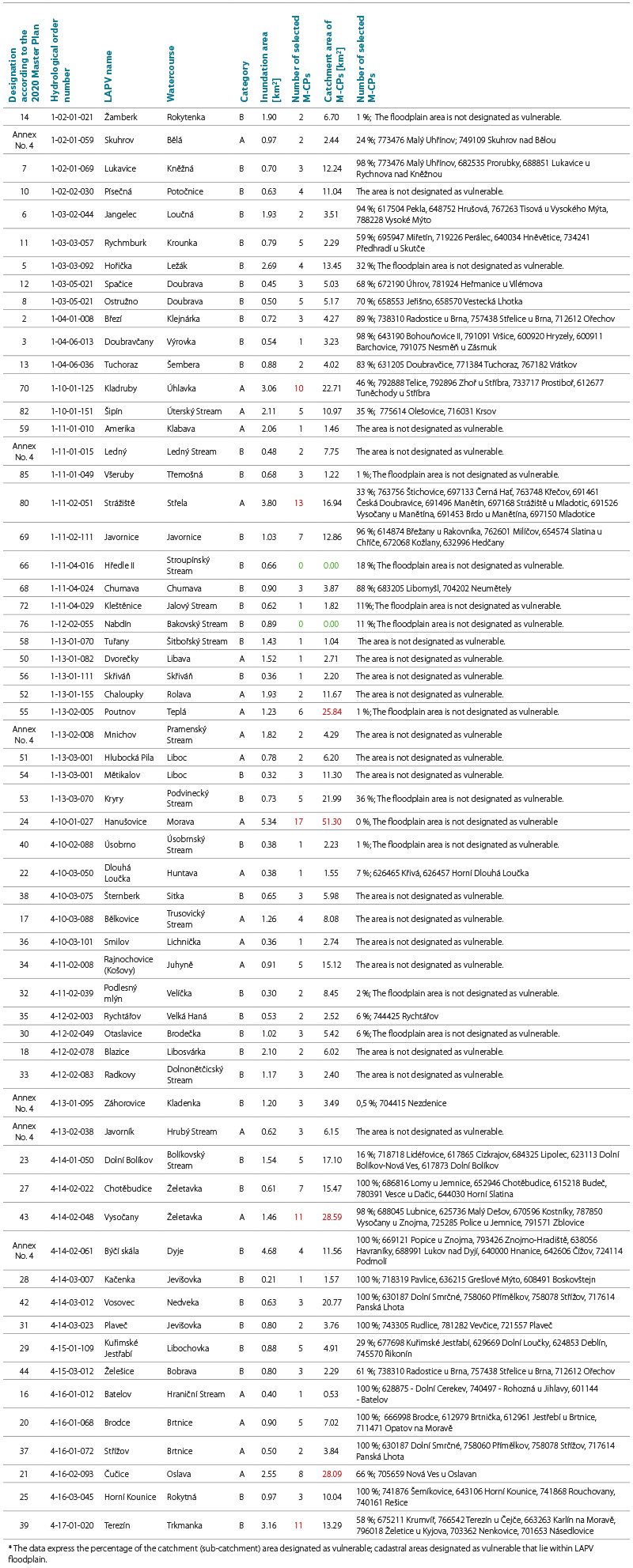

A total of 61 protected areas of natural water accumulation (LAPV – Sites for Surface Water Accumulation) were evaluated. Below, Tab. 1 summarises the results of the analyses of the selection of modified critical points and the vulnerability of areas with respect to the Nitrates Directive for the selected LAPV.

Tab. 1. Summary of analysis results for selected protected areas of natural water accumulation

Focusing on the results of the modified CP analysis, two sites – Nabdín and Hředle II – can be considered non-risk areas. No modified CPs were identified in their catchments. At the other end of the spectrum, i.e., among sites with a high number of selected M-CPs (>10 M-CPs), are Kladruby (10 M-CPs), Trkmanka (11 M-CPs), Vysočany (11 M-CPs), Strážiště (13 M-CPs), and Hanušovice (17 M-CPs). The second value derived from the analysis is the total area of the catchments – the contributing areas of the M-CPs. This specifies the area where measures will be necessary to mitigate or eliminate erosion processes. The sites with the largest total M-CP catchment areas are Poutnov (25.84 km², 6 M-CPs), Čučice (28.09 km², 8 M-CPs), Vysočany (28.59 km², 11 M-CPs), and Hanušovice (51.30 km², 17 M-CPs).

Tab. 1 also includes data on the percentage of vulnerable zone relative to the total area of the LAPV catchment (or sub-catchment) and a list of cadastral units designated as vulnerable zones located within the inundation zone of the LAPV.

The database also includes the results of the analyses of CLCs carried out in the catchments for all 61 LAPV. However, the article does not present the full overview, particularly due to the temporal variability of these data. The entire process is still ongoing, and unfortunately proceeding very slowly. In practice, the term “completed” means that the project has been finished and the property settlements have been carried out. Implementation of the so-called Joint Facilities Plan, which is most closely related to the water-management function of the landscape, has often been postponed to a later date. The differences in the progress of land consolidations across cadastral areas within LAPV catchments are currently significant. For example, in the LAPV Strážiště catchment, on the Střela river, which includes the largest number of cadastral units (98), only 14 of them have completed land consolidations due to the predominantly forested character of the area. For Kryry Reservoir, which is closest to implementation, 13 out of a total of 23 cadastral units have been completed, and six are in progress.

DISCUSSION

As a case study, Terezín LAPV on the Trkmanka has already been presented several times in this article. It is a reservoir located in the gently undulating landscape of southern Moravia, with its catchment beginning in the north as far as Ždánický Forest. The reservoir itself, however, lies in open agricultural land, and almost the entire surrounding area constitutes the contributing areas of the M-CPs. The character of these areas is shown in Fig. 6. The soils are often overly dry and degraded, lacking the capacity to retain water, and are therefore particularly susceptible to erosion during flash floods as well as to wind erosion. If a decision is made to construct the reservoir, additional erosion-control measures will be necessary to prevent rapid sedimentation. The presented calculation method will assist the designer both in planning the measures and in verifying their effectiveness.

Fig. 6. Terezín protected area of natural water accumulation – current state

Vulnerable zones are clearly related to agricultural land management. Therefore, the rights and obligations within them are determined primarily by the Ministry of Agriculture, even though the impacts also affect the aquatic environment. The extent of these areas is regularly updated, with the basis for these updates being the results of groundwater monitoring. Excessive amounts of nitrates from groundwater subsequently enter surface waters through springs and drainage, where they become part of other natural processes. However, for surface waters in future reservoirs, the potential presence of pesticide substances and their metabolites may pose a greater problem, with elevated nitrate levels serving as an indicator that undesirable substances from crop production are entering the waters. The issue of pesticides, their monitoring, and their environmental impacts is still a developing field; the active substances and products used change from year to year. In view of the above, it would be appropriate to focus attention on vulnerable zones, prioritising those in the catchments of Group A LAPV, assumed to be potential sources of drinking water. It has been shown that some of these pollutants persist in waters long after their use has been banned.

Comprehensive land consolidations take place continuously over long periods. During their implementation, the requirements for their execution have gradually evolved. Initially, their primary objectives were property settlements with landowners and the consolidation of plots of land. Emphasis on erosion-control measures developed gradually, and after periods of drought, the need for water retention in the landscape is now highlighted. CLC can thus be an ideal tool for mitigating or eliminating the phenomena identified during the search for M-CPs. Their disadvantage, on the other hand, lies in the high administrative, time, and financial demands during the design, consultation, and implementation phases. Their execution then affects the use and functionality of the landscape for many years.

When constructing a larger hydraulic structure, it is always necessary to consider changes in the affected catchments, which may influence existing or future CLCs. Therefore, the entire relevant LAPV catchment should always be identified and taken into account in spatial planning documents. CLCs should then be completed and evaluated across the whole catchment, together with any necessary erosion-control interventions.

Water-management authorities should also place greater emphasis on the protection of the relevant catchments in their decision-making. However, this would require additional legislative tools, for example in the form of a protection zone for a future water source. One of the existing options is also the increased use of prohibitions or restrictions on activities in designated protected areas of natural water accumulation, or alternatively, the extension of these areas to cover entire LAPV catchments [32].

CONCLUSION

For a long time, sites designated for future surface water accumulation have been protected within spatial planning; however, targeted protection of the catchments of these reservoirs is lacking. Investigations carried out within the project showed that general environmental protection may not be sufficient in these cases. The better condition of some sites is attributed more to natural conditions and the development of the landscape over the years than to targeted measures. This applies particularly to points that are critical for concentrated runoff and the transport of washed-off material into watercourses during heavy rainfall events. The article further documents the impact of diffuse, predominantly agricultural activities in the affected catchments. These are long-term negative effects with lasting consequences, even in the event of targeted interventions. It is therefore necessary to introduce legislative protection of the relevant catchments now, particularly in cases where the future reservoir is intended to serve as a source of drinking water.

Acknowledgements

This article was written within the framework of the Czech Technology Agency project No. SS02030027, Water Systems and Water Management in the Czech Republic under Climate Change Conditions (Water Centre), as part of WP3 – Water for People.

The Czech version of this article was peer-reviewed, the English version was translated from the Czech original by Environmental Translation Ltd.