ABSTRACT

Atmospheric deposition is the most significant source of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface waters in the Czech Republic. These substances originate predominantly from combustion processes. Through deposition, PAHs reach the Earth’s surface and are subsequently washed into surface waters. Although the state and the private sector have implemented a number of measures in recent decades to reduce emissions, not only from major pollution sources but also from households (local heating), these substances continue to have a significant impact on the aquatic environment. Selected PAHs are included on the list of priority substances due to their proven adverse effects on aquatic organisms and human health, and strict environmental quality standards have been set for them in surface water and biota matrices. Consequently, most surface water bodies do not achieve good chemical status according to the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC. Research in the Výrovka river basin (a tributary of the Elbe river) comprehensively addressed PAH contamination in relevant matrices of the aquatic environment and in Schreber’s big stem red moss (Pleurozium schreberi), which is a suitable indicator of air pollution. At the same time, PAH fluxes in wet deposition in selected urban locations were monitored for comparison. The origin of PAHs was assessed using fingerprinting, based on the analysis of ratios between individual PAHs in the monitored matrices, enabling the distinction between petrogenic and pyrogenic sources.

INTRODUCTION

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are ubiquitous substances in the environment [1]. Their presence is due not only to the widespread use of substances and final products containing PAHs, but primarily to combustion processes, during which PAHs are formed by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels and organic materials [2]. Primary emissions of PAHs into the atmosphere occur predominantly in the gaseous phase; however, relatively rapid condensation and sorption onto fine particulate matter take place as flue gases cool. The rate of sorption increases with increasing molecular weight [3], while very strong particle sorption and hydrophobicity are characteristic of PAHs with three or more aromatic rings. PAHs reach the Earth’s surface through atmospheric deposition. Only a portion of them is subsequently transferred into surface waters by erosion, as confirmed in the model catchments of the Suchý and Martinický streams [3]. A substantial proportion of PAHs remains bound to the Earth’s surface (vegetation, soil). In soils, PAHs undergo degradation at different rates depending on the specific hydrocarbon. This process is fastest in the case of naphthalene, which, due to its physicochemical properties, deviates from the behaviour of other PAHs; its DT50 is reported to be 6.1 weeks. In higher-molecular-weight PAHs, degradation is substantially slower: 168 weeks for benzo(a)pyrene and 522 weeks for benzo(k)fluoranthene [4].

Another important source comprises point and diffuse sources of pollution, including stormwater overflows of public sewer systems. PAHs enter waters both through runoff from impervious surfaces associated with roads and traffic [5] and from areas treated with coating materials and polyaromatic-based waterproofing products, as well as from the combustion of fossil fuels and smoking; according to Skupinská [6], a single cigarette releases 20–40 ng of benzo(a)pyrene into the environment.

Many PAHs exhibit toxic properties affecting aquatic organisms, animals, birds, and humans; mutagenic, carcinogenic and teratogenic effects, as well as adverse impacts on the immune system, have been demonstrated [7]. For these reasons, selected PAHs were classified as priority substances for the aquatic environment and designated as priority hazardous substances under Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, as amended by Directive 2013/39/EU [8, 9]. Current environmental quality standards (EQS) are in the order of nanograms per litre; the strictest standard applies to the carcinogenic benzo(a)pyrene, at 1.7 × 10-4 μg ∙ L-1 (annual average). The forthcoming amendment to Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council extends the list of PAHs for which environmental quality standards are established; some of these standards are revised, and a new comparison with EQS recalculated to a benzo(a)pyrene ecotoxicity equivalent is introduced. Although the environmental quality standard expressed as an annual average is abolished, a value at a comparable concentration level is newly established for fluoranthene (a tightening from the current 6.3 × 10-3 μg ∙ L-1 to 7.62 × 10-4 μg ∙ L-1). For the above reasons, it remains necessary to continue addressing PAH emissions and their impacts on the environment and the status of waters.

The following article focuses on the assessment of PAH concentrations in atmospheric deposition, in Schreber’s big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi), and in other environmental matrices within the Výrovka model catchment. It also presents a comparison with PAH loads from wet deposition in an urbanised environment.

Based on the ratios of individual PAHs, their origin was also assessed. For the purposes of this article, two main categories of pollution sources were considered: petrogenic (PETRO) and pyrogenic (PYRO).

The purpose of this comparison is to contribute to understanding the sources and pathways through which PAHs enter surface waters, where they lead to the failure to achieve good status under the Water Framework Directive. The Czech Republic ranks among the countries with the highest proportion of water bodies failing to achieve good status due to PAHs. This is associated with an obligation to implement measures aimed at reducing their inputs. In the model catchment, a substance balance was established with the objective of comparing atmospheric deposition of PAHs with their substance export under typical agricultural landscape conditions. The inclusion of additional matrices and sites was intended to confirm further risk factors and to address the following questions:

- What is the PAH load from atmospheric deposition (short-term – precipitation, and long-term – moss and humus), and how is it influenced by additional factors such as urbanised areas, traffic, and industry?

- What is the relationship between atmospheric deposition of PAHs and their occurrence in the watercourse – is there an influence of rainfall–runoff events? What proportion of deposited substances is exported from the catchment, and what proportion is retained by the environment?

- Which PAH source is dominant for the aquatic environment, and how does the composition of PAHs differ among individual matrices?

METHODOLOGY

PAHs were monitored and evaluated that contribute to the failure to achieve good status of water bodies and at the same time exhibit a significant potential for long-range atmospheric transport, often over considerable distances from primary pollution sources.

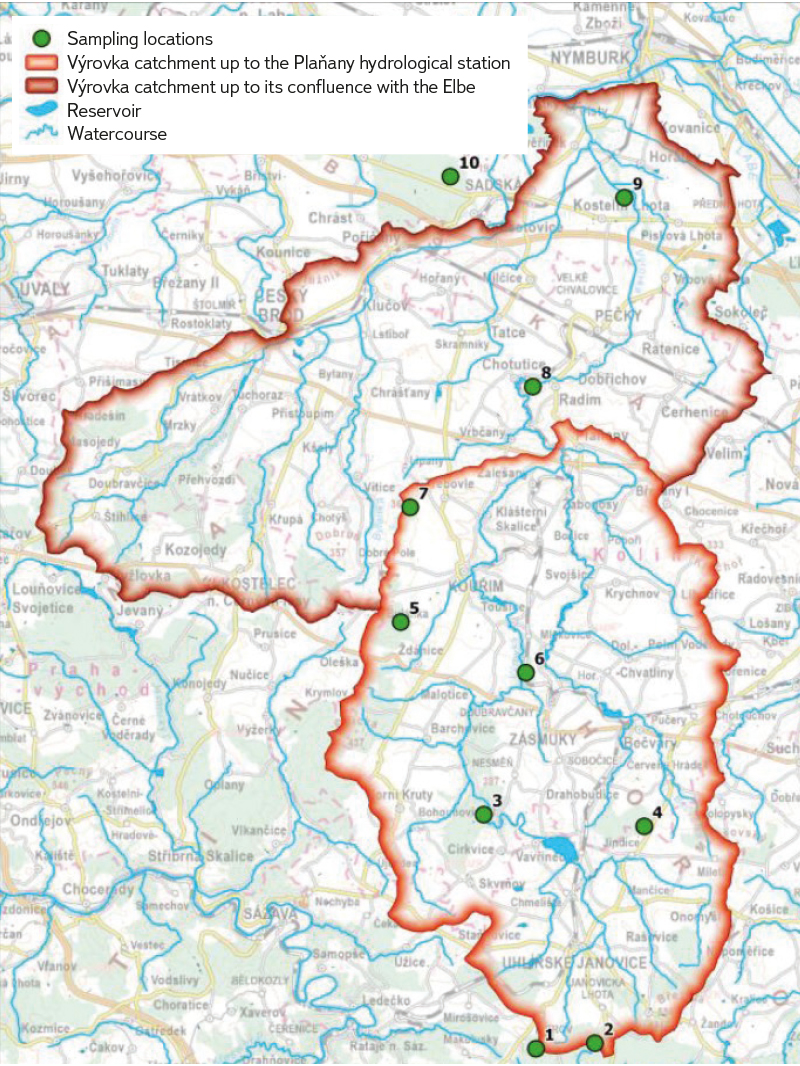

For the purposes of the project, the Výrovka catchment was selected, specifically its upper part upstream of Plaňany hydrological station (operated by the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute; CHMI).

The Výrovka is a left-bank tributary of the Elbe, and its catchment lies entirely within the Central Bohemian Region. The part of the catchment upstream of the Plaňany profile covers an area of 264.35 km² and consists of 30 fourth-order sub-catchments. Catchment elevation ranges from 208 to 550 m a.s.l. The hydrographic network has a total length of 362 km of watercourses and includes 70 reservoirs.

According to data from the Land Parcel Identification System (LPIS), there is 19,000 ha of agricultural land within the area of interest, of which 94 % consists of arable land. The main crops that were the most widely cultivated in 2022 included winter wheat, winter oilseed rape, maize, spring barley, and sugar beet.

To compare the distribution of PAHs across different components of the environment, the following matrices were sampled:

- wet deposition in an open area (bulk) – monthly precipitation, 2021–2022,

- throughfall deposition – monthly precipitation, 2021–2022,

- surface water – grab sampling once per month, 2021–2022,

- suspended sediment load – daily composite sample, 2021–2023,

- suspended sediment contamination – centrifuged sample, 2021–2023,

- humus (biologically stable humified layer) – after removal of the litter and fermentation layers; two samplings at 10 sites, samples representing a longer time period (sampling in 2021 and 2022),

- Schreber’s big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi) – two samplings at 10 sites, samples representing a longer time period of approximately three years (sampling in 2021 and 2022).

The Výrovka model catchment, with the location of the gauging station and sampling sites for individual matrices, is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Výrovka river catchment with locations of surface water and atmospheric deposition sites

Atmospheric deposition was collected using stainless steel rain gauges with a collection area of 52.4 cm² in order to obtain a sufficient sample volume for the analytical determination of PAHs (2,000 mL). The upper part of the rain gauges was fitted with a stainless steel bowl with 3 mm diameter openings to prevent the deposition of coarse particles and the ingress of insects. If an insufficient amount of precipitation was recorded in a given month, the sample was collected after a two-month exposure period. Monitoring of atmospheric deposition was carried out from June 2021 to June 2022 in an agricultural landscape between the municipalities of Třebovle and Klášterní Skalice. A second site was selected in a forest stand west of the municipality of Zásmuky (Fig. 1), where two rain gauges were installed (bulk and throughfall).

The volume of collected precipitation during individual sampling campaigns was measured and compared with precipitation totals for the same period obtained from the nearest CHMI climatological stations, namely Cerhenice and Vavřinec–Žíšov rain gauge stations. The mean monthly discharge for the Výrovka was calculated from mean daily discharges at the CHMI gauging profile No. 082000 – Výrovka–Plaňany, that is, at the same profile where surface water and suspended sediment sampling was carried out.

From the amount of precipitation and the determined concentrations of the monitored PAHs in precipitation, an estimate of the total atmospheric deposition for the Výrovka catchment was calculated. The calculation used concentration results of PAHs in deposition collected in an open area (bulk sampling). The annual substance export of individual PAHs by the watercourse was calculated by multiplying the mean monthly discharge by their measured concentrations in surface water. The daily substance export of PAHs associated with suspended sediment was derived from daily concentrations of total suspended solids multiplied by the mean value of the sum of PAHs measured in eight suspended sediment samples (2,161 μg ∙ kg-1).

To compare the occurrence of PAHs in atmospheric precipitation in a highly urbanised environment, sites in Prague-Podbaba (within the TGM WRI premises) and Ostrava-Přívoz were selected at the end of 2021. At these sites, monthly bulk and throughfall precipitation sampling was carried out from December 2021 to October 2023.

The TGM WRI premises in Prague are located on the northern edge of the city between the heavily trafficked Podbabská road and the Vltava river, which flows around the central wastewater treatment plant. In the Ostrava-Přívoz district, rain gauges were installed on the roof of a garage belonging to the TGM WRI Ostrava Branch (bulk) and within the grounds of a nearby kindergarten on Špálova Street (throughfall). Approximately 1 km north of both monitoring stations is the Svoboda coking plant, and 3 km to the south-west are the BorsodChem MCHZ chemical works.

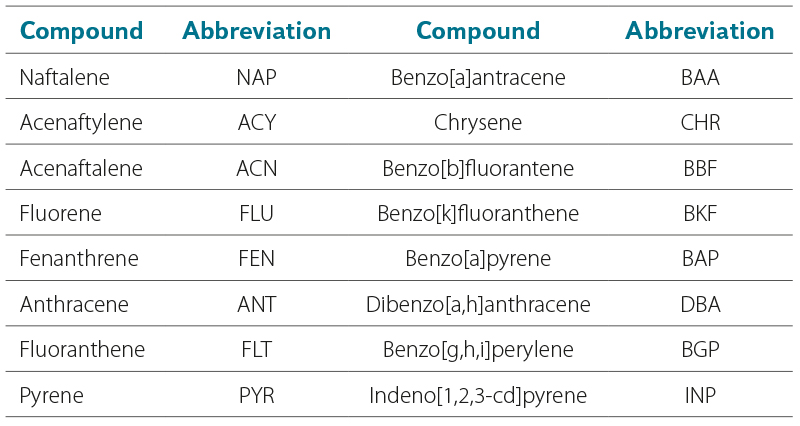

In aqueous samples, 15 PAHs (Tab. 1) were analysed using liquid chromatography on an Agilent 1260 Infinity II instrument with fluorescence detection. Separation was achieved using a Pinnacle II PAH column (4 μm, 150 × 4.6 mm, Restek) and a mobile phase composed of components A: methanol and B: water with the addition of 5 % methanol.

Tab. 1. List of analyzed PAHs and their abbreviations

PAHs in moss and humus samples were analysed using gas chromatography with a triple quadrupole EVOQ GC-TQ (Bruker) by mass spectrometry in MS/MS mode.

Schreber’s big red stem moss (Pleurozium schreberi) was collected during two sampling campaigns in spring 2021 and summer 2022 at 10 sites within the Výrovka catchment, and in 2023 at varying distances from road II/611 (Poděbradská) and the D11 motorway (Hradecká) west of the municipality of Sadská, in open areas (without the influence of throughfall deposition).

Samples for PAH determination were collected in aluminium foil bags. The bags were transported to the laboratory in an in-vehicle cooling box and subsequently stored in a freezer. Prior to analysis, frozen samples were gradually manually cleaned of unwanted impurities, and the green apical parts of the moss were separated for analysis. The green moss tissues were ground in a vibratory mill under liquid nitrogen and subsequently dried by vacuum lyophilisation. They were then analysed by liquid chromatography with MS/MS detection.

Humus samples were collected, transported, and stored until analysis in the same manner as moss samples. Frozen humus samples were sieved through a steel sieve with a mesh size of 2.00 mm, dried by lyophilisation, and analysed in the same way as moss.

To determine the origin of PAHs, published diagnostic ratios between selected PAHs were used to estimate their petrogenic or pyrogenic origin.

RESULTS

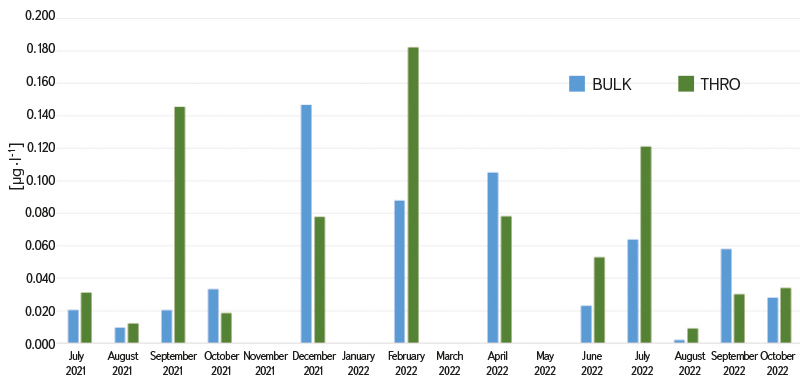

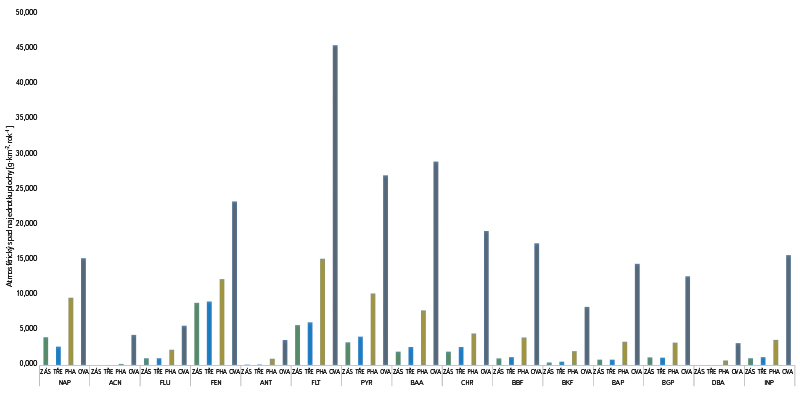

PAH concentrations in collected precipitation water varied considerably over the course of the year (Fig. 2). The results show a clear monthly pattern of PAH contamination in precipitation, as well as a marked difference between the winter and summer periods. The increase in PAH concentrations during winter is primarily influenced by local heating sources, depending on meteorological conditions. Among individual PAH compounds, fluoranthene, phenanthrene, pyrene, and benzo[a]pyrene predominated in atmospheric precipitation. Comparison of the summed PAH concentrations indicates that their levels in throughfall deposition (labelled THRO in the figures) are mostly higher than in bulk deposition (labelled BULK). This is attributable to the binding of PAHs to fine particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5), which is subsequently deposited on vegetation. From there, PAHs are washed off during precipitation events.

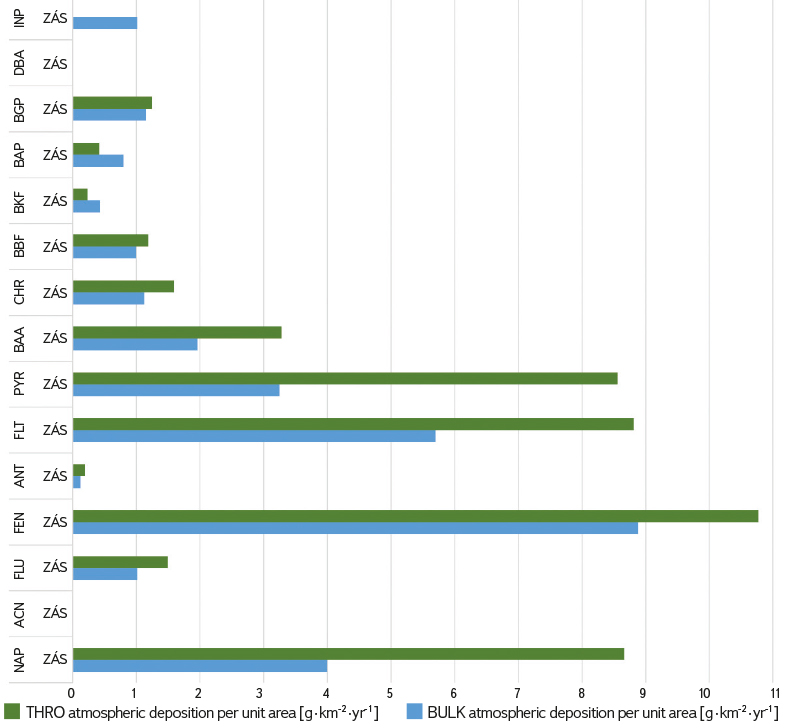

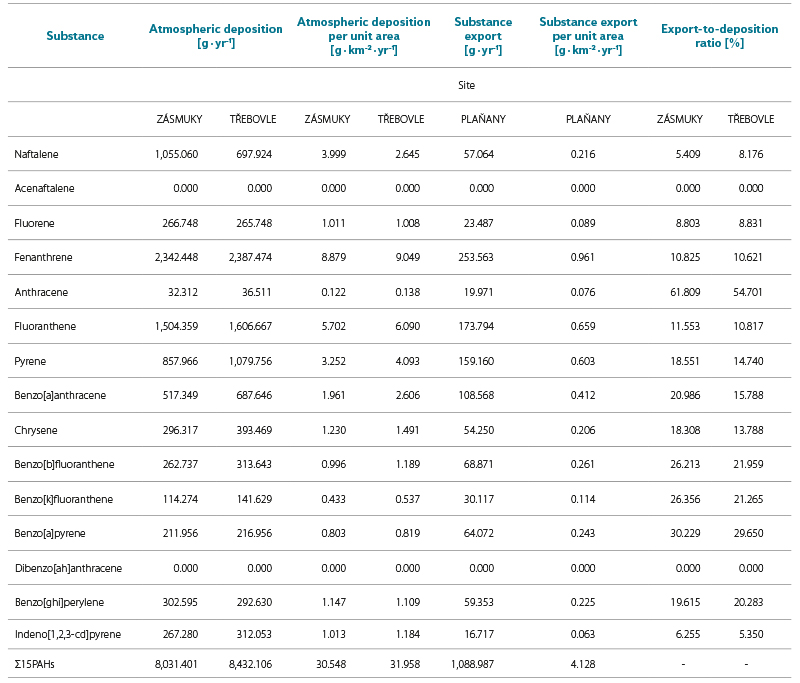

In the next step, the magnitude of atmospheric PAH deposition per unit area was calculated for the Výrovka catchment, expressed in g ∙ km-2 ∙ yr-1, for both bulk and throughfall deposition. The highest values were observed for naphthalene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene, and pyrene. The graph for the Zásmuky site (Fig. 3) shows differences in deposition between bulk and throughfall for individual PAHs. Interestingly, for higher-molecular-weight PAHs, this difference is not as pronounced.

Fig. 2. Sum of PAHs in bulk and throughfall precipitation at the Zásmuky site

Fig. 3. Atmospheric deposition of PAHs per unit area by bulk deposition and throughfall at the Zásmuky site

The highest PAH concentrations in the surface water of the Výrovka were observed for naphthalene (January, June, and September). During winter, concentrations of naphthalene, phenanthrene, fluoranthene, and pyrene predominated. Based on the ratio of fluoranthene to pyrene, which exceeded 1 in most measurements, the origin of PAHs from combustion processes can be inferred [10]. It was found that the relative contribution of PAHs in surface water is significantly lower compared to atmospheric deposition.

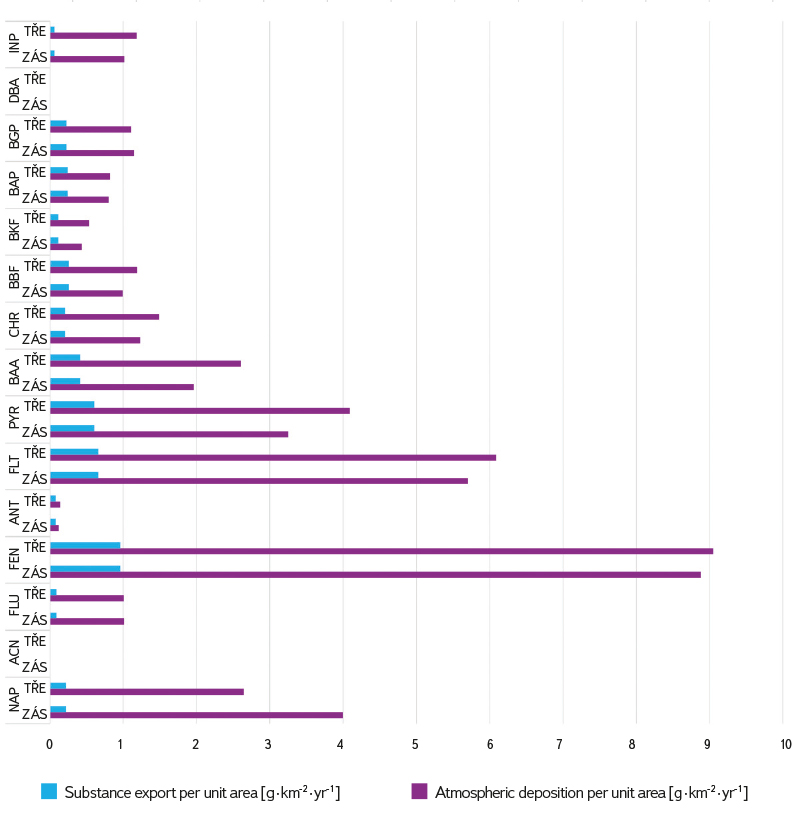

Throughout the entire monitoring period, discharges at the Výrovka–Plaňany river profile were recorded at an hourly time step. From these data, mean daily and monthly discharges were calculated in order to perform an approximate balance of PAH export from the Výrovka model catchment. The results are compared with atmospheric deposition in Tab. 2. Despite differences between the two sites, the magnitude of atmospheric deposition in Zásmuky and Třebovle is comparable. When the determined annual deposition is multiplied by the area of the catchment upstream of the Výrovka–Plaňany river profile, the resulting PAH load in this catchment amounts to 8.075–8.448 kg ∙ yr-1. In contrast, PAH export at the Výrovka–Plaňany profile was substantially lower, reaching 1.089 kg ∙ yr-1. This relationship is clearly illustrated by the graph in Fig. 4. The upper soil layers and vegetation cover retain the majority of these non-polar organic substances from atmospheric deposition, which readily sorb onto fine particulate matter. They are subsequently transported into surface waters by erosional runoff. Another, albeit less significant, source of PAH contamination of surface waters is direct deposition onto water surfaces; there are several dozen fishponds within the catchment.

Tab. 2. Total atmospheric deposition of PAHs by wet deposition at the Zásmuky and Třebovle sites and PAHs transport by the Výrovka river in the Plaňany site

Fig. 4. Total atmospheric deposition (BULK) of PAHs at the Zásmuky and Třebovle sites and PAHs transport in the Výrovka-Plaňany river site

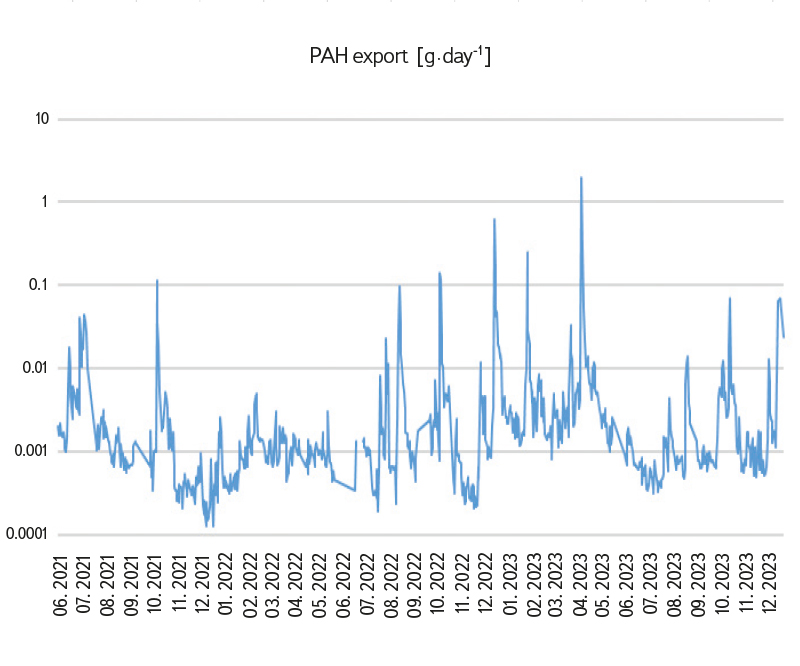

The above-mentioned PAH export from the Výrovka catchment is in fact underestimated, as PAH concentrations in surface water increase at higher discharges during rainfall–runoff episodes. For this reason, PAHs were also analysed in suspended sediments and during periods of increased discharge caused by intensive precipitation. Suspended sediment sampling for PAH analyses was carried out under standard flow conditions (n = 6) and under increased discharges (n = 2) of approximately 0.9 m³ ∙ s-1 (the mean annual discharge is 0.688 m³ ∙ s-1) [11]. Daily PAH exports associated with suspended sediments are shown in Fig. 5. However, the overall PAH balance in suspended sediments is not significant: under maximum discharge conditions it amounted to 2 g ∙ day-1, and a total of 6.2 g of PAHs was transported from the catchment by suspended sediments at the Plaňany profile over the monitored period.

Fig. 5. Transport regime of PAHs in suspended sediments at the Plaňany profile, 2021–2023

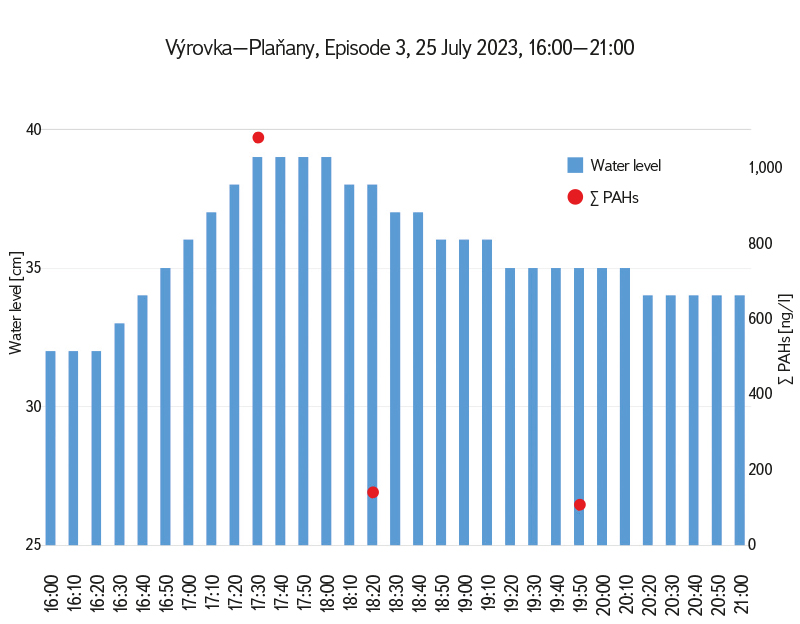

In 2022, surface water sampling was carried out at the CHMI monitoring profile Výrovka–Plaňany during three rainfall–runoff episodes. Sampling was conducted using a remotely controlled automatic sampler. Precipitation totals recorded at the Cerhenice climatological station were highest during the third sampling episode on 29 June 2022, when 38.9 mm of precipitation fell within two hours (16:10–18:10). During this rainfall–runoff event, three partial water samples were collected, as documented in Fig. 6. The first sample was taken at the maximum water level reached in the receiving water body, while the subsequent two were taken during the recession phase of the discharge. PAHs were determined in a homogenised sample. PAH concentrations were highest at peak discharge (1,078 ng ∙ L-1), after which they decreased markedly to 139–106 ng ∙ L-1. For comparison, the mean annual concentration of Σ PAHs derived from monthly sampling at the Výrovka–Plaňany profile was 57 ng ∙ L-1. PAH export during the three-hour period of increased discharge in the receiving water body (17:00– 20:00) was estimated at 1.13 g. This day recorded the highest precipitation total in 2022 and was followed by a further seven days with daily precipitation totals exceeding 25 mm. Although PAH concentrations increase substantially during rainfall–runoff episodes, particularly in their initial phase, the total export from the catchment also increases but remains far below the magnitude of atmospheric deposition over the total catchment area.

Fig. 6. Concentration of PAHs in surface water during precipitation-runoff episode No. 3

At higher temperatures, oxidation processes involving atmospheric trace gases (NOX, SO2, O3) are more effective, and therefore PAH degradation proceeds more rapidly in summer than in winter. In the gaseous phase, PAHs become part of wet atmospheric deposition through interfacial gas-liquid exchange during below-cloud scavenging, whereas PAHs associated with solid particles are more efficiently removed by in-cloud scavenging processes as a result of diffusion, impaction, and interception [12].

As already mentioned in the introduction, sites in Prague-Podbaba (within the TGM WRI premises) and Ostrava-Přívoz were selected to compare the occurrence of PAHs in atmospheric precipitation in a highly urbanised environment. At these sites, monthly bulk and throughfall precipitation sampling was carried out from December 2021 to October 2023.

Urbanised environments are significant areas for PAH deposition due to the high concentration of emission sources and specific conditions that influence their distribution and deposition. Differences in PAH concentrations between the two urban sites are pronounced. The Ostrava region has long ranked among the areas most heavily burdened by PAHs in the Czech Republic. Although the PAH load at the Prague site was lower than in Ostrava, it was higher than at the Zásmuky and Třebovle sites within the Výrovka catchment. Elevated PAH concentrations at the selected sites clearly confirm the influence of the urbanised environment on atmospheric PAH deposition. Data from Zásmuky, Prague-Podbaba, and Ostrava-Přívoz also indicate marked differences in PAH concentrations between throughfall and bulk precipitation. These differences reflect the variability of pollution sources and environmental conditions across different urbanised environments.

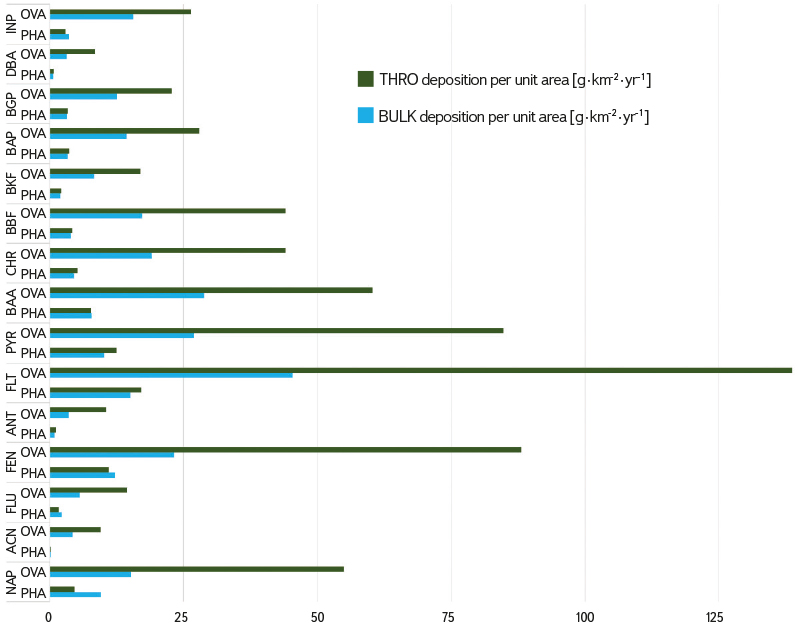

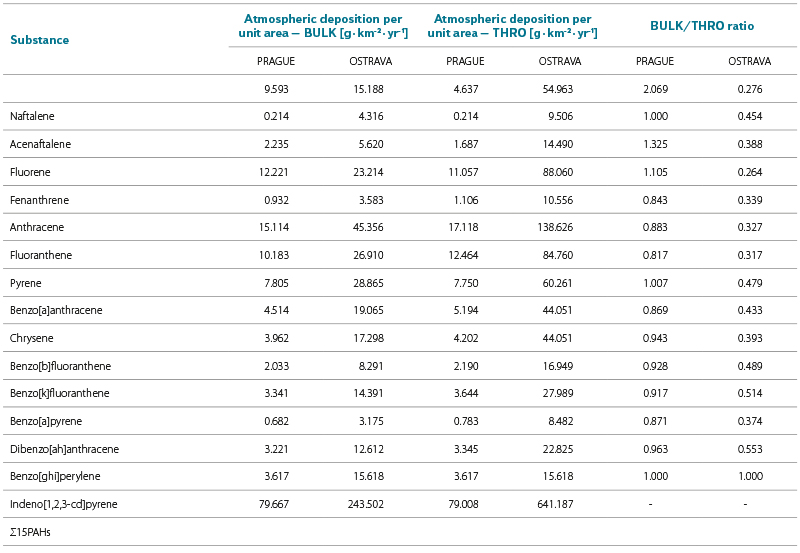

Using the same approach as applied at the monitored sites within the Výrovka catchment, the magnitude of atmospheric PAH deposition per unit area was calculated for urbanised environments (Fig. 7). However, deposition was not compared with PAH export by surface waters, as both monitoring stations represented only small areas within large urban agglomerations. The results are presented in Tab. 3.

Fig. 7. Comparison of atmospheric deposition in bulk and throughfall at the Ostrava-Přívoz and Prague-Podbaba sites

Tab. 3. Total atmospheric deposition of PAHs at the Ostrava-Přívoz and Prague-Podbaba sites

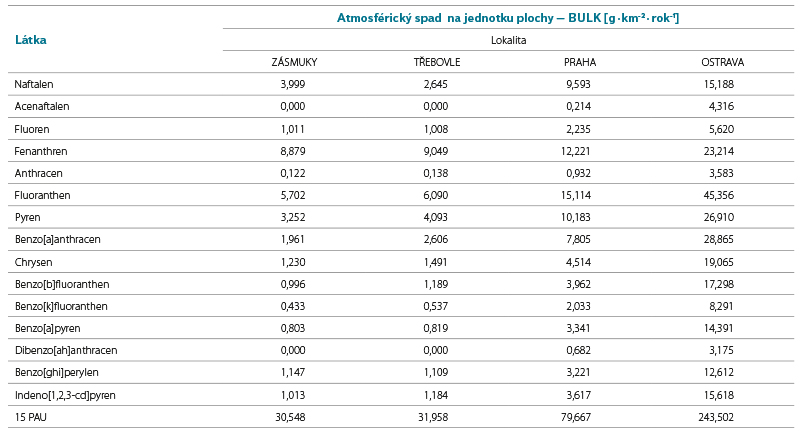

A comparison of the total atmospheric PAH deposition at all four monitored sites is presented in Tab. 4 and Fig. 8.

Tab. 4. Comparison of total atmospheric deposition of PAHs at the Zásmuky, Třebovle, Prague-Podbaba, and Ostrava-Přívoz sites

Fig. 8. Comparison of total atmospheric deposition of PAHs at the Zásmuky, Třebovle, Prague-Podbaba and Ostrava-Přívoz sites

The results presented in Tab. 4 and Fig. 8 demonstrate that in terms of PAH emissions, the Ostrava-Přívoz site represents an extremely heavily burdened area. Given that local heating sources burning solid or liquid fossil fuels are virtually absent at this site, the observed load is associated primarily with intensive industrial activity and, to a lesser extent, with increased traffic density in the area. The PAH load at the Prague-Podbaba site is substantially lower than at Ostrava-Přívoz; however, compared to sites within the Výrovka catchment, it is more than double. The relatively high PAH deposition values observed in Prague can be attributed to a large extent to traffic density along the adjacent main arterial road, as well as to other potential sources. The Zásmuky and Třebovle sites exhibit lower and nearly identical levels of PAH emissions, which may be explained by lower settlement density, limited industrial activity, and lower traffic intensity. The Třebovle site, located in the lower part of the Výrovka catchment, is slightly more affected by PAH deposition than the Zásmuky site, which is situated in a forest stand between the municipalities of Zásmuky and Barchovice. Total PAH deposition at the Ostrava-Přívoz site is approximately 7.6 times higher than at the Třebovle site.

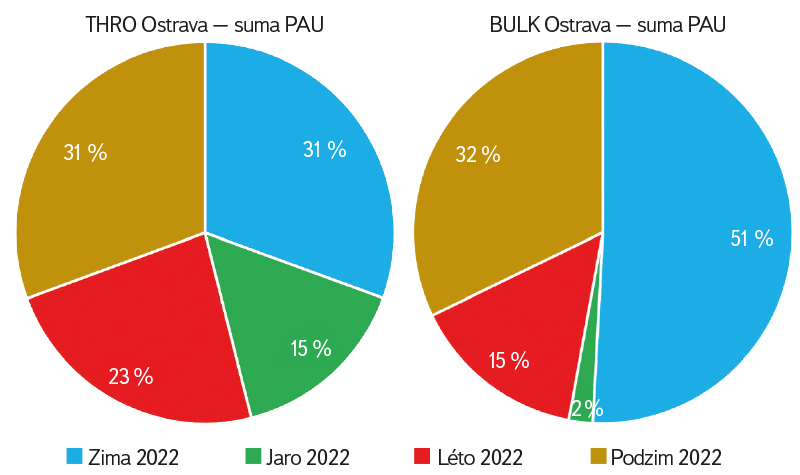

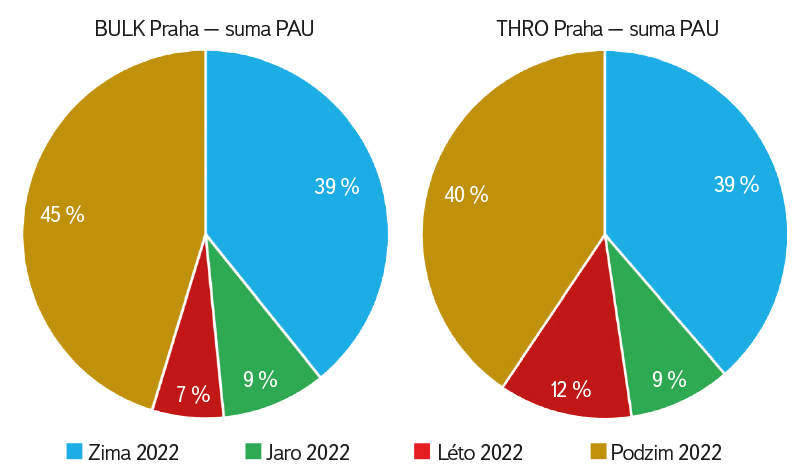

The graphs shown in Figs. 9 and 10 indicate considerable variability in Σ PAH concentrations over the course of the calendar year.

Fig. 9. Total PAHs concentration in precipitation by seasons in 2022, Prague-Podbaba site

Fig. 10. Total PAHs concentration in precipitation by seasons in 2022, Ostrava-Přívoz site

A comparison of deposition data from Prague and Ostrava, with regard to the degree of urbanisation and industrial activity, provides an informative perspective on the environmental influences affecting both cities. Prague, as the capital of the Czech Republic, has a pronounced urban character, with extensive areas inhabited by a dense urban population. Although Prague is also an industrial centre, urban development and the service sector prevail over heavy industry, which influences both the magnitude and composition of PAH emissions and their subsequent deposition.

Ostrava has historically been known as a major centre of heavy industry, particularly metallurgy and chemical production; however, at present only the coking industry remains from the original industrial spectrum. This sector continues to represent a key source of emissions of harmful substances into the atmosphere, especially PAHs released during high-temperature coal processing. These emissions contribute substantially to the local environmental burden and, through atmospheric deposition, are associated with degraded air quality.

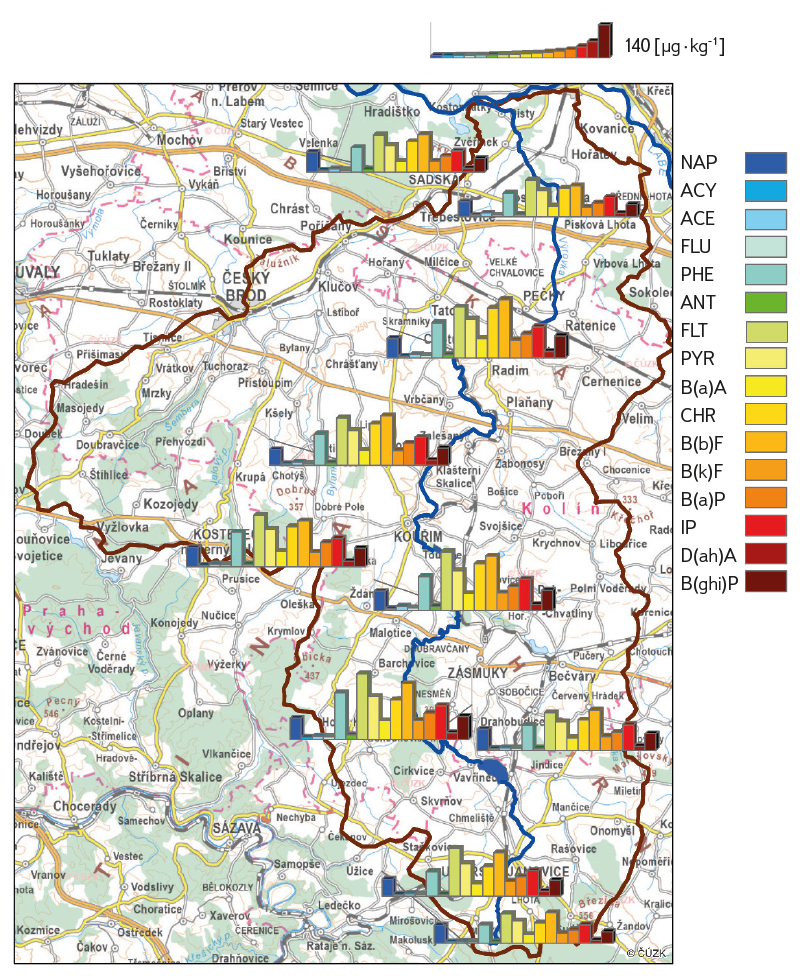

PAHs in moss and humus in the Výrovka catchment

In moss, the highest relative contributions to the sum of PAHs were observed for NAP, FEN, FLT, PYR, and BBF, while the lowest contributions were found for ANT, ACY, and ACN. In 2021, the highest Σ PAHs in moss were measured at samples from the nearby sites 3 and 4 in the southern part of the catchment (Fig. 1). A large number of cases with elevated concentrations of individual PAHs was also identified in moss from site 7, where higher deposition of heavy metals (HMs) had been indicated. By contrast, the lowest Σ PAHs were measured in moss at the spatially distant sites 5 and 9. In 2022, the highest Σ PAHs were recorded in moss samples from sites 4 and 2 in the southern part of the Výrovka catchment, while the lowest values were observed at sites 10 and 6 in the northern and central parts of the catchment. Σ PAHs in moss in 2022, which was on average 2 °C warmer than 2021, were approximately 60 % higher than in 2021, with the largest increase observed for NAP. Although sorption of PAHs onto solid sorbents decreases with increasing temperature, the elevated PAH levels in 2022 were probably associated with increased atmospheric PAH deposition from more polluted air, for example as a result of enhanced volatilisation and sublimation of PAHs from major sources in the surrounding area. In contrast to HMs, the central part of the catchment, with the exception of site 7, contains lower Σ PAHs than the southern and northern margins of the catchment, probably due to the influence of emissions from a denser road network. The main sources of PAHs in the catchment include the combustion of organic fuels in local and nearby domestic and commercial heating units, exhaust emissions from road traffic, and specific industrial activities such as the production and recycling of asphalt mixtures (Běchovice, Kolín, Poříčany, Kutná Hora). Long-range transport of PAHs from more distant large-scale sources, such as the Prague and Pardubice agglomerations, may also be considered. In the summer of 2022, the entire study area was affected for several days by smoke from a forest fire in Bohemian Switzerland.

In the Výrovka catchment, PAHs from local and distant sources become mixed, and therefore relatively large temporal and spatial variations in instantaneous PAH deposition levels can be expected.

PAH contents in moss from the Výrovka catchment were 42 % lower in 2021 and 13 % higher in 2022 than those measured in moss from the forested area of Šumava in 2018. The results indicate relatively high background PAH levels even in Šumava.

Long-term accumulated Σ PAHs in humus were 1.5–15 times higher than in moss. PAH contents are influenced by the humus (carbon) content of the collected sample. Unfortunately, in the Výrovka catchment, particularly in its central part, younger coniferous forests prevail, and a warm and relatively dry climate leads to slow spruce growth and the formation of a thin humus layer with an increased proportion of the mineral soil fraction. Such conditions complicate reproducible humus sampling in individual years. At the northern and southern margins of the Výrovka catchment, the humus layer in pine and spruce forests is thicker. In humus samples, the highest PAH contents were determined for CHR, FLT, PYR, and FEN, while the lowest contributions to Σ PAHs were observed for ACN, ANT, and ACY. The highest PAH contents in humus in 2021 were measured in samples from sites 3 and 7, while the lowest were recorded at sites 9 and 10 in the northern part of the catchment. In 2022, the highest PAH contents were found in samples from sites 3 and 8, whereas the lowest values were observed at sites 2 and 10, located at opposite ends of the catchment. The high variability of the results is attributed to pronounced differences in forest humus quality within the Výrovka catchment, as well as to long-term local variability in PAH deposition resulting from a higher number of local PAH sources and the absence of a more homogeneous (background) PAH concentration in the atmosphere.

Fig. 11 illustrates the distribution of PAHs in forest surface humus in the Výrovka catchment in 2021.

Fig. 11. Distribution of PAHs contents in forest humus in the Výrovka catchment in 2021

Forest humus in the Výrovka catchment contained lower Σ PAHs in 2021 and 2022 than reference forest humus from a forested area in Šumava. This is due to the less developed humus layer in the Výrovka catchment, with a higher proportion of the mineral fraction of forest soil (22–30 %), which has a lower adsorption capacity for binding PAHs than the mineral fraction in humus from Šumava (6–17 %). In the forests of the Výrovka catchment, PAHs are adsorbed within a relatively shallow surface layer of forest soil as a result of the poorly developed humus layer. In contrast, in Šumava forests, PAHs are bound to humus horizons and do not penetrate into the underlying mineral soil, provided that the humus layer is not disturbed by animal activity or forest management practices.

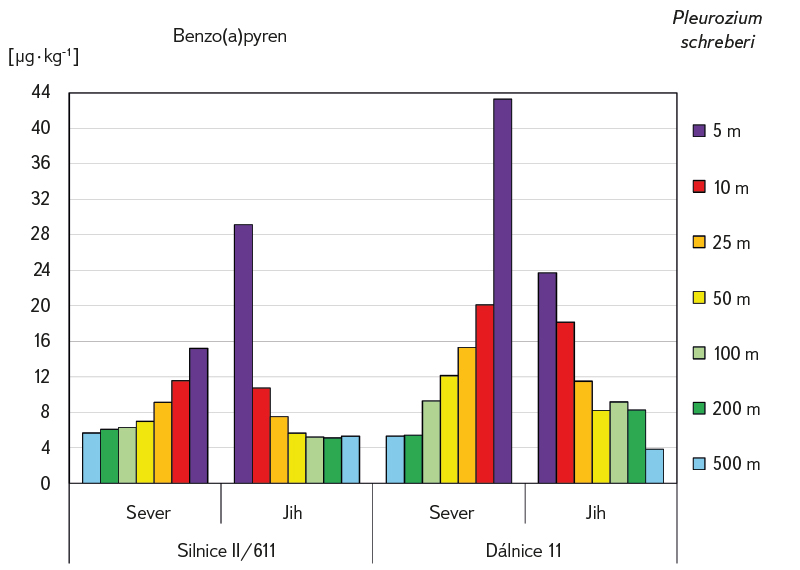

PAH contamination in the vicinity of roads

In the immediate vicinity of road II/611, relatively high contents of NAP, FLT, FEN, and BBF were detected in moss, while the lowest contents were observed for ACN, ACY, and ANT. Similarly, near the D11 motorway, the highest PAH contents in moss were recorded for NAP, BBF, FLT, and FEN, and the lowest for ACN, ACY, and ANT.

Σ PAHs in moss along road II/611 decrease on both sides to a distance of about 100 m, while along the D11 motorway Σ PAHs decrease to a distance of approximately 200 m, but not beyond. These distances therefore represent the main deposition zones along the monitored road segments. As in the case of heavy metals, a solid barrier in the form of an earthen embankment or a high road fill on the southern edge of road II/611 and the northern edge of the D11 motorway significantly slows the dispersion of PAH aerosols into the surrounding area and increases the level of current PAH deposition in the immediate vicinity of the roads. This situation is clearly illustrated in Fig. 12 for the case of BAP. Sucharová and Holá [13] reported statistically significantly higher PAH contents in moss within 50 m of the D1 motorway near Divišov in 2010. They also observed a very rapid increase in PAH contents in moss at a reference site as a result of forest residue burning after timber harvesting, even at a considerable distance from the moss sampling location [13].

Fig. 12. Decrease in BAP content in moss with distance from road II/611 and motorway D11 near Sadská in the summer of 2023

Although the solubility of PAHs in water is low, runoff of PAHs bound to dust particles and oil leaks into watercourses from drainage systems conveying runoff from road surfaces and their surroundings must be considered, even at distances of tens or, in some cases, hundreds of metres.

Relatively the highest contributions to Σ PAHs along road II/611 were identified for BBF, FLT, CHR, and PYR, while the lowest contributions were observed for ACN, ACY, ANT, and BAA. Σ PAHs in humus on both sides of the road decrease up to a distance of approximately 50 m. This is followed by fluctuations in PAH contents in humus at greater distances as a result of logging and other forestry activities on the northern side at the U Kocánka site, while the end of the southern transect is apparently influenced by deposition from the D1 motorway. In the vicinity of the D11 motorway, low Σ PAHs were detected in humus up to a distance of 25 m, due to the removal of the original humus layer and the still insufficient development of a new humus layer. Σ PAHs depend on the type of humus and its organic carbon content [14]. North of the D11 motorway, Σ PAHs decrease up to a distance of approximately 200 m, whereas on the southern side this decrease is disrupted by increased Σ PAHs at distances of 100 m and 500 m south of the motorway.

The irregular pattern of Σ PAHs is caused by fluctuations in carbon content in the samples (the relationship is not statistically significant, probably due to the small number of samples), logging and forestry activities that disturb the humus horizon, as well as the potential influence of activities at a shooting range and an industrial zone, including asphalt mixture production, on the southern edge of the forest near Poříčany. Along the D11 motorway, the main contributors to Σ PAHs in humus are NAP, PYR, FLT, and FEN, while ACN, ACY, DBA, and ANT contribute the least. These results further indicate that elevated, long-term accumulated Σ PAHs in forest soils extend to distances of several tens of metres and at least up to 100 m from the edges of heavily trafficked roads. From PAH-contaminated zones adjacent to roads, PAHs can most readily enter watercourses via drainage systems, either bound to low-molecular-weight humus fractions or associated with solid humus and soil particles transportable by water.

Determination (Estimation) of PAH origin

Determining the origin of PAHs represents a key step in assessing environmental burden and in designing effective measures to reduce their emissions. PAH sources can generally be divided into two main categories: pyrogenic (products of incomplete combustion of organic materials and fossil fuels) and petrogenic (associated with leaks of petroleum products and their processing). Estimation of PAH origin in the environment is most commonly based on a combination of diagnostic chemical ratios of individual PAH compounds, knowledge of local sources, and analysis of spatial and temporal trends in concentrations.

To distinguish PAH sources, so-called diagnostic ratios between the concentrations of defined compounds are used. The principle of the method is based on the assumption that different hydrocarbons are generated depending on the specific PAH formation process and its temperature conditions. A typical example is the fluoranthene/pyrene ratio (FLT/PYR), for which values greater than 1 indicate a pyrogenic origin, while values below 1 suggest a petrogenic origin. Other commonly used indicators include the ratios ANT/(ANT + FEN), BAA/(BAA + CHR), and INP/(INP + BGP), which together allow for a more robust classification of sources [15–21].

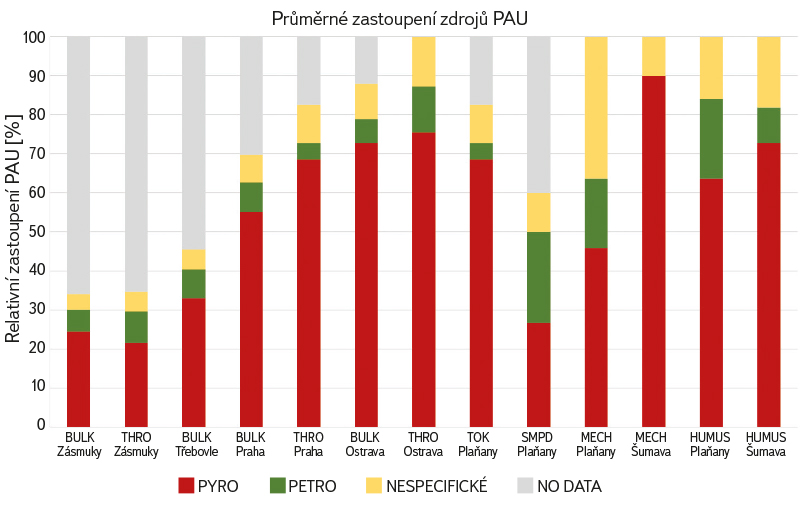

Fig. 13 shows the average composition of PAHs in selected matrices sampled in the Výrovka catchment, Prague, and Ostrava. The evaluation is based on a total of nine selected PAH diagnostic ratios. The categories used to determine source origin are PYRO, PETRO, NON-SPECIFIC (ratios were calculated but do not clearly indicate a specific type of pollution source), and NO DATA (concentrations required for ratio calculations were below the limit of quantification or unavailable).

Fig. 13. Average contribution of PAHs sources in selected matrices

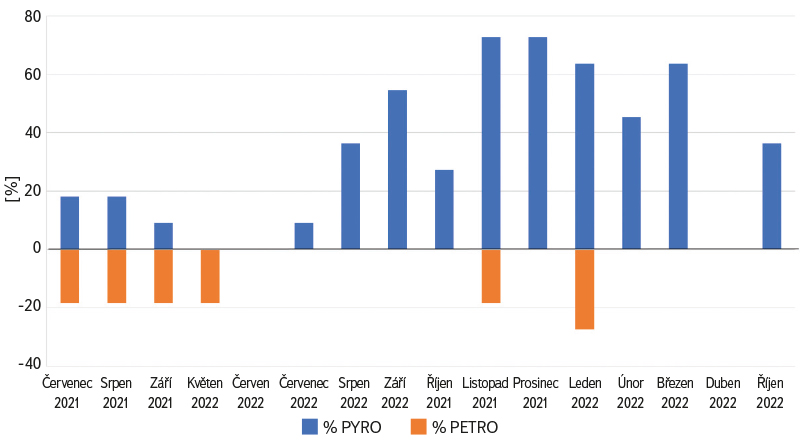

In the case of significantly or extremely polluted urbanised sites, the origin of PAH contamination could be specified most clearly (Prague, Ostrava). A predominantly pyrogenic origin of PAHs was confirmed, including in Prague at a distance of approximately 25 m from the main arterial road Podbabská. By contrast, at the Zásmuky and Třebovle sites, concentrations of selected PAHs were below the limit of quantification (LOQ), and the diagnostic ratio method could therefore be applied only to some compounds. In such cases, the ratio between the sum of low-molecular-weight and high-molecular-weight PAHs whose concentrations exceeded the LOQ (Σ LMW / Σ HMW) was used to estimate source origin. When this ratio is less than 1, a pyrogenic origin can be inferred; when greater than 1, a petrogenic origin is indicated [21]. Fig. 14 illustrates a clear difference in PAH origin in total wet deposition (bulk) at the Třebovle site, with months of the non-heating season arranged on the left side of the graph and months of the heating season on the right. During the summer months, petrogenic and pyrogenic PAH sources were nearly balanced, whereas in the colder part of the year a pyrogenic origin predominated. In summer, PAH concentrations were lower and more frequently below the LOQ; consequently, a smaller number of diagnostic ratios between individual PAHs could be used to estimate their origin. For example, in contrast to the winter months, during the period from May to June 2022 only LMW hydrocarbons exceeded the LOQ, which are primarily of petrogenic origin. The proportional representation of sources is expressed as percentages in Fig. 15.

Fig. 14. Origin of PAHs in wet atmospheric deposition (bulk) at the Třebovle site

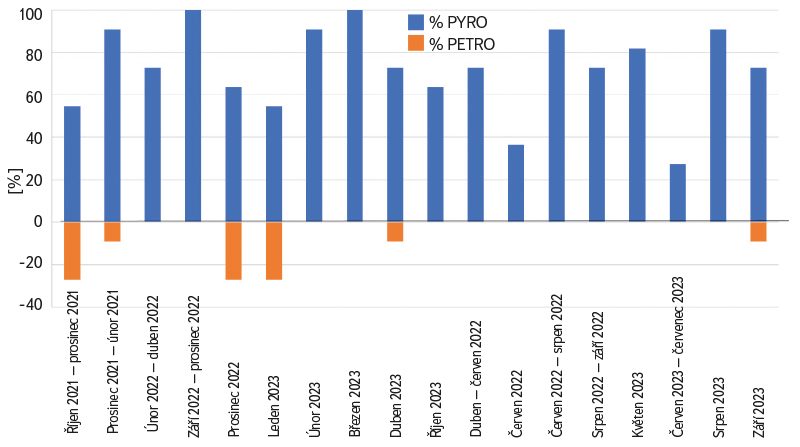

A comparison of the same matrix at the substantially more heavily burdened site in Ostrava is summarised in Fig. 15. In contrast to Třebovle, a weaker seasonal influence is observed for pyrogenic PAHs at this site, whereas petrogenic PAHs were present only during the heating season and in September 2023, which was characterised by below-average temperatures. These differences are related to higher industrial activity, the size of the urban agglomeration, and probably also to more frequent fuel handling.

Fig. 15. Origin of PAHs in wet atmospheric deposition (bulk) at the Ostrava site

Results obtained using diagnostic ratios should be interpreted with caution, as their values may change under the influence of environmental processes. It is possible to apply correction factors that account for the effects of the physicochemical properties of PAHs and changes caused by inter-phase transport and degradation [21]. Even with the application of correction factors, however, the results remain only an estimate.

DISCUSSION

Research conducted in the Výrovka catchment model catchment and in urbanised areas (Ostrava, Prague), focusing on the analysis of PAHs in various types of environmental matrices, provided a more detailed insight into the dynamics of their concentrations over the course of the calendar year, their behaviour in the environment, and the factors influencing their levels.

Atmospheric deposition represents the dominant pathway by which PAHs enter subsequent components of the environment. Environmental load expressed as deposition per unit area and year was comparable at both Zásmuky and Třebovle sites within the Výrovka catchment (Σ 15PAHs 30.548 and 31.958 g ∙ km-2 ∙ yr-1, respectively), although the sites differ in character (forest versus agricultural land use). In Prague, in the vicinity of a major arterial road (TGM WRI premises along Podbabská street), PAH deposition was 2.5 times higher than at the sites within the Výrovka catchment. An extremely high PAH load was confirmed in the urban area of Ostrava-Přívoz (243.5 g ∙ km-2 ∙ yr-1), located near a coking plant approximately 800 m north of the monitoring site, in an area dominated by westerly, south-westerly, and north-westerly wind directions. Ostrava-Přívoz is thus burdened by PAH deposition more than seven times compared with the rural sites of Zásmuky and Třebovle. For the carcinogenic benzo(a)pyrene, deposition at the Prague site was more than four times higher (3.341 g ∙ km-2 ∙ yr-1) than at the Výrovka catchment sites, while deposition at the Ostrava site was more than seventeen times higher (14.391 g ∙ km-2 ∙ yr-1). The contribution of benzo(a)pyrene to the Σ 15PAHs deposition amounted to 2.6 % at the Výrovka sites, 4.5 % at the Prague site, and 5.9 % at Ostrava-Přívoz.

PAH concentrations were higher in throughfall precipitation than in wet deposition collected in open areas (bulk). This indicates that vegetation – particularly leaves and tree branches – provides surfaces for the adsorption of PAHs from the atmosphere, as confirmed at the Zásmuky and Ostrava-Přívoz sites, where throughfall deposition exhibited markedly higher PAH concentrations than bulk wet deposition. In some cases, however, PAH concentrations may be higher in bulk deposition, which can be attributed to specific meteorological conditions or emission events during the sampling campaign, as observed at the Prague-Podbaba site during summer.

Calculated PAH fluxes associated with wet deposition and surface water in the Výrovka catchment confirmed that the larger proportion of deposited PAHs remains within the environment, with only a fraction entering surface waters through erosion and, to a lesser extent, through direct deposition onto water surfaces. Σ 15PAHs deposition over the catchment area upstream of the Plaňany profile was calculated to be 8.075–8.448 kg ∙ yr-1, whereas PAH export at the Výrovka–Plaňany profile was substantially lower, amounting to 1.089 kg ∙ yr-1. During rainfall–runoff events, PAH concentrations increase during the initial rise in discharge and at peak flow, as confirmed by the analysis and mass balance of PAHs in suspended sediments; however, this increase was not as pronounced as initially expected. The cumulative PAH export via suspended sediments amounted to 6.2 g over the period 2021–2023 and 1.13 g during the first three hours of the most significant storm event in 2022 (38 mm in 3 h and 50 mm in 24 h).

The spatial distribution of PAH contents in moss and humus further highlights the importance of transport corridors and local heating sources. Elevated PAH contents in the vicinity of roads II/611 and D11 confirm that emissions from road traffic constitute a significant contribution of PAHs to the environment, primarily via particulate matter contaminated by incomplete fuel combustion and tyre wear.

The observed differences between individual years and seasons document not only the influence of local sources but also the possible involvement of long-range transport and episodic events. In 2022, for example, an increase in PAH contents in moss was recorded, which can be partly explained by the influence of a smoke plume from the forest fire in Bohemian Switzerland. These findings underline that even in relatively less burdened areas, substantial increases in PAH concentrations may occur as a result of regional or transboundary transport.

CONCLUSION

Analysis of diagnostic ratios, seasonal dynamics, and spatial distribution indicates that pyrogenic processes represent the dominant source of PAHs at the assessed sites, in particular the combustion of fossil fuels in local heating systems and industrial sources, with a substantial contribution from road traffic. Petrogenic sources play only a supplementary role; nevertheless, their influence cannot be entirely excluded, especially in the immediate vicinity of roads or industrial areas. The results confirm the need for a combined approach to PAH source assessment, integrating chemical indicators with analyses of emission scenarios and the influence of long-range transport.

PAHs are ubiquitous substances and, particularly in urbanised areas, pose a significant risk not only to the aquatic environment but also to human health. The currently discussed amendment to Directive 2008/105/EC proposes a substantial tightening of the environmental quality standard (annual average) for fluoranthene and introduces the recalculation of selected PAHs to a benzo(a)pyrene-equivalent risk. Following the adoption and transposition of the directive into national legislation, new approaches to the assessment of the chemical status of surface water bodies will need to be implemented.

The conducted research confirmed that atmospheric deposition is a significant source of PAHs in the environment, particularly in industrial areas and in the vicinity of intensive road traffic. However, its influence is not negligible even in agricultural landscapes. At the same time, the results confirm that the land surface and its properties play a crucial role in the retention of PAHs and in the protection of watercourses. In addition to the necessary improvement of air quality, appropriate measures to achieve good water status with respect to PAHs therefore include erosion control and improved stormwater management.

Nevertheless, a need remains for more detailed research and monitoring of PAHs across individual environmental matrices, including atmospheric deposition, wind erosion, and rainfall–runoff episodes, together with the evaluation of measures aimed at reducing their emissions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic (No. SS0203027), Water Systems and Water Management in the Czech Republic under Climate Change Conditions (Water Centre).

The Czech version of this article was peer-reviewed, the English version was translated from the Czech original by Environmental Translation Ltd.